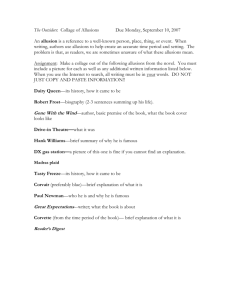

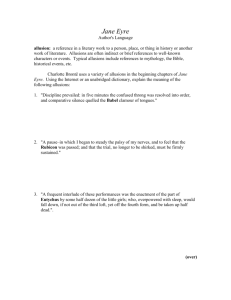

Document 11001641

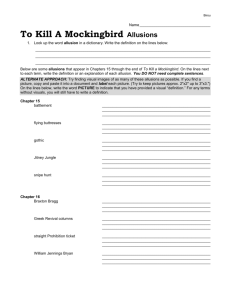

advertisement