Recollection and Second-Order Skepticism Department of Philosophy, Georgia State University Brett Mullins

advertisement

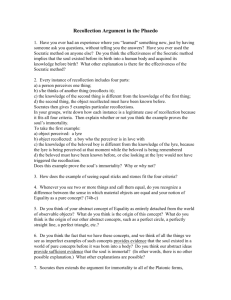

Volume 1 (2013) Recollection and Second-Order Skepticism Brett Mullins Department of Philosophy, Georgia State University Abstract Platonic Recollection is a method of knowledge attainment by which an agent acquires certain insights into immutable, immaterial absolute ideas. The recollecting agent can make inferentially valid judgments regarding whether a perception is an instance of an absolute idea. Both culturally and historically, these judgments vary. As a result, error must be widespread among agents. While recollection potentially results in certain first-order knowledge, the ensuing widespread error makes necessary the uncertainty of second-order knowledge in many cases. Though one may know an absolute idea, they may not know whether they indeed know the idea. This second-order uncertainty undermines first-order knowledge attributions. This disables differentiation between the knowledgeable and those who lack knowledge from which skepticism follows. Plato’s notion of knowledge as insights into immutable, immaterial ideas gained through the method of recollection yields a skepticism that undermines the epistemic certainty attained by agents. While Plato’s epistemology potentially tracks knowledge attribution in cases regarding absolute ideas, it fails to produce second-order knowledge; such certainty would entail that one’s beliefs, inferentially acquired through recollection, correspond with particular absolute ideas. Through the comparison of the intentional states of various epistemic agents, the attainment of knowledge through recollection gives rise to skeptical doubts that disables differentiation between those possessing knowledge and those without. It is not within the scope of this paper to provide an original interpretation of Plato’s epistemology; rather, I intend to illustrate the pertinence of second-order considerations in evaluating theories of knowledge. In the Phaedo, Plato considers an example where one is holding a bundle of sticks and is deliberating whether any two of the present sticks are equal in length. Due to the imprecision of human sense organs, one cannot accurately identify two sticks that are exactly equal in length, weight, and so I am grateful to George Wrisley for introducing me to both epistemology and how one should go about doing philosophy. 34 Brett Mullins/Volume 1 (2013) forth. This is to say that no perceptible relation among or between the sticks is identical to the notion of equality; further, no abstraction from perception is identical to the notion of equality. 1 A requisite to this consideration is the notion of equality itself. While one's sense organs may produce fallible beliefs regarding the properties of the sticks in consideration, one can imagine two sticks that are wholly equal in the relevant properties. One cannot have gathered knowledge of equality from perception as no two sticks can illustrate equality. This phenomenon leads Plato to conclude that one must have knowledge of the equal prior to this event to allow the contemplation to be possible.2 Since knowledge of the equal cannot be the result of experience, as no two objects are perceptibly equal, knowledge must be attained through some other mechanism. Considering that knowledge of the equal is a requisite for contemplating whether two objects are equal with regard to some property, knowledge of some property must precede the contemplation of that property regarding sense experiences. If humans begin sensing and contemplating at birth, then, Plato posits humans must have such knowledge prior to birth.3 If humans have knowledge prior to birth and during corresponding contemplations, then they must have lost or forgotten it at birth as it appears that infants lack such knowledge. The attainment of knowledge, therefore, becomes a process of recollection by which one is reminded of something, such as equality, by the apparent properties of sense perception.4 If the members of the stack of sticks are all potentially unequal, then knowledge of the equal cannot come from the relations among the sticks themselves. If it is the case that knowledge comes from relations among the sticks, then knowledge of the equal could not exist in the absolute or infallible sense intended; it would only exist through abstraction as an approximation of such an idea. Knowledge must instead originate elsewhere than the sensible world. This is to say that the object of knowledge is an idea that is not manifested physically, but exists in the sense that it is bound with one’s immaterial properties.5 It is worth noting that the “present argument is no more concerned with the equal than with absolute beauty and the absolute good and the just and the holy, and, in short, with all those things which 1 Plato, Phaedo, trans. Harold North Fowler (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999), 74b. Plato, Phaedo, 75a. 3 Plato, Phaedo, 75c. 4 Plato, Phaedo, 75e. 5 Dominic Scott, Recollection and Experience: Plato’s Theory of Learning and Its Successors (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 68-9. 2 35 Brett Mullins/Volume 1 (2013) we stamp with the seal of absolute.”6 Plato posits that through the mechanism of recollection one can attain knowledge of any absolute quality. Recollection can thus be formulated as a method of knowledge attainment by which an epistemic agent is confronted with sense perception corresponding to an absolute quality and, subsequently, reacquaints with the idea. As a result, relevant judgments may be passed regarding instances both material and imaginary. Epistemic agents form inferentially justified beliefs from knowledge of these absolute ideas of the sort ‘X is Q’ or ‘X is not Q’. X corresponds to a sense perception of an object, a relation, an event, etc., while Q represents an absolute quality. These intentional states or judgments are both widespread and potentially simple beliefs held by epistemic agents. For instance, equality in length among the bundle of sticks above exemplifies this form. This relationship is not necessarily binary; a potential belief of this sort is ‘X is more Q than Y,’ where Y corresponds to an additional sense perception of an object, a relation, an event, etc. Given that one has attained relevant knowledge through recollection and employed valid inferential reasoning, such beliefs can be said to be justified. The potential exists that beliefs of the sort considered above held by epistemic agents can be contrary or contradictory to one another. This is best evidenced by comparing cultural and historical conceptions of particular absolute ideas, such as justice and beauty. Consider the institution of slavery, laws regarding property rights, famed art, and classical compositions of music. It is reasonable to make the claim that epistemic agents from different cultures or historical periods will potentially judge these cases of justice or injustice, beautiful or not beautiful differently. Further, the properties of absolute qualities cannot change over time. Consider the consequences of the meaning of equality changing at the moment of one's birth. This is to say that prior to birth, equality held the meaning X; yet, when one recalls equality through corresponding sense experience, such as with contemplating relations among a stack of sticks, equality holds meaning Y. Under these conditions, change produces an illogical result as one cannot recall the current state of something that has undergone change. This introduces an element of arbitrarity to knowledge such that any attainment of 6 Plato, Phaedo, 75c-d. 36 Brett Mullins/Volume 1 (2013) knowledge is both time dependent and potentially contrary to any past or future iteration of the absolute idea.7 Since contrary judgments exist culturally and historically regarding the same instances (slavery, art, etc.) and absolute ideas cannot change over time, this suggests that widespread error exists among epistemic agents. A theory that results in widespread error attributed to contending agents need not be rejected on this ground alone. This result conforms to intuitions about others’ beliefs in cases in which one specializes in a field of study or if one possesses privileged information. If individuals thought that their beliefs about their health represent the best current theories of medicine, then they need not go see a medical specialist when they are ill. Likewise, it is absurd to reject a claim of insider trading for the reason that an informed shareholder’s beliefs are true, while the uninformed market’s beliefs are false. This conclusion invokes several questions, however, regarding the mechanism of recollection and what it means to know: why does such widespread error exist; are contradictory false judgments the result of pure speculation, inferential error, or both; why did the epistemic agents that espouse false beliefs not partake in the method of recollection? Besides holding justified beliefs, what differentiates epistemic agents who underwent recollection from those who did not? Consider the epistemic agent that recollects the idea of justice such that all judgments of ‘just’ and ‘unjust’ are inferentially justified. This individual is confronted with contrary or contradictory judgments regarding justice from others. Only one of the conflicting belief sets can be correct.8 Since there appears to be no difference between those who underwent recollection and those who did not, other than potentially having justified judgments, there exists an individual or social uncertainty as to whether or not the recollecting agent’s judgments are in fact justified. The result is that the justification with which one possesses knowledge of knowing an absolute quality is less than the justification with which one, through recollection, knows an absolute quality. Thus, skepticism emerges regarding this second-order 7 By arbitrarily, I mean that past and future iterations of an absolute idea need not hold meanings related to one another if it is allowed that the meaning of absolute ideas can change. In such a case, any particular meaning attained through recollection is potentially arbitrary. 8 In isolated instances, different ideas of justice will yield the same judgment: X is just or X is not just. ‘Belief sets’ refers to collections of judgments from various instances. Differences in ideas of justice will emerge as the numbers of intentional states considered increases. 37 Brett Mullins/Volume 1 (2013) uncertainty, because agents do not know if they can be wrong, which undermines first-order attributions of knowledge.9 Plato’s epistemology both posits the existence of absolute ideas and provides a mechanism by which one can attain knowledge of such ideas. These premises provide intuitive explanatory power regarding how one can know absolute ideas and why there is potentially such widespread disagreement in various cases. An implication of the mechanism of recollection, however, is that even if one comes to know a particular absolute idea one will lack corresponding second-order knowledge and, thus, not know that one indeed knows the absolute idea. Since the potential exists for contending judgments and ensuing uncertainty regarding any absolute idea, there exists a second-order skepticism among all such knowledge. Second-order uncertainty is captured in contemporary theories of knowledge; however, these theories posit a probabilistic justificatory relationship between the epistemic agent and the object of knowledge, which is distinct from the intimate relationship attained through recollection.10 The probabilistic notion treats both first and second-order knowledge as uncertain. In cases of recollection, the epistemic agent faces no first-order uncertainty; however, second-order uncertainty is apparent and becomes a skepticism that obscures the knowledgeable. Put another way, by participating in recollection, one’s first-order knowledge is infallible, while one’s second-order knowledge is fallible. The skepticism arises from the fallibility of the second-order knowledge, which undermines the epistemic status of the first-order knowledge. The significance of this conclusion is that the mechanism by which an epistemic agent attains infallible knowledge of absolute ideas yields second-order uncertain knowledge. The doctrine of recollection marks certainty as a criterion for knowledge. As a result of the presence of this uncertainty, the recollecting epistemic agent does not possess second-order knowledge regarding absolute ideas. This undermines the epistemic status of the knowledgeable because, not only do knowledgeable agents not know that they indeed know such ideas, but they are categorized together with agents who do not know and do not know whether or not they know. The knowledgeable are obscured by the widespread secondorder uncertainty, disabling differentiation between the two groups; thus, a skepticism emerges. 9 See Alexander S Harper, "Fallibilism, Contextualism, And Second-Order Skepticism," Philosophical Investigations 33 (2010): 343-4. 10 Jon Moline, Plato’s Theory of Understanding (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1981), 7-9. 38 Brett Mullins/Volume 1 (2013) One may object to this conclusion on the grounds that the characterization of recollection as a short-term mechanism is misguided. One does not simply undergo recollection at some point in time and, subsequently, possess knowledge of an absolute idea; rather, recollection is a long-term process of concept formation that begins at birth. Depending on one’s experiences, some ideas are potentially easier to attain than others; consider the absolute qualities of equality (in measurement) and justice, for instance. It appears that equality is attained much earlier on in life than is justice. The temporal period between birth and the full attainment of an absolute idea can be described as a period of partial recollection.11 This is to say that one must amend and develop their conception of absolute ideas as they progress through this extended mechanism of recollection. In this regard, this theory can be held as revisionary in so far as upon gaining a greater understanding of the absolute idea one updates their previous conception.12 Partial recollection provides an avenue for explanation of the potential for disagreement and widespread error among epistemic agents. Since the possibility exists that different agents will be at different stages of recollection at any given time, disagreement regarding the object of recollection is possible. This accounts for the contending judgments and ensuing widespread error that brings about second-order uncertainty and skepticism. In this case, contending judgments regarding absolute ideas are built into the account of recollection and are not a problematic byproduct. This is to say that such conflict among epistemic agents is an inevitability when considering ideas, which are more difficult to attain. Since this widespread disagreement is inevitable or necessary, the present worries regarding the ensuing second-order uncertainty are extinguished. Even if it is assumed that partial recollection accounts for the worries evoked by conflicting judgments and that such conflict is a necessary condition for collective knowledge attainment, a further skepticism of another variety arises to undermine recollection.13 Epistemic agents are either in a state of ignorance, partial recollection, or full recollection regarding an absolute idea; since recollection occurs through remembrance, one who lacks sensory experience regarding an absolute idea is considered ignorant with regard to that idea. If one forms a judgment regarding an absolute idea, then they are either 11 Scott, 20-1. This formulation of recollection is referred to in Scott “Recollection and Experience” as the Kantian view. Scott is concerned with accounting for recollection as a theory of learning rather than a theory of knowledge. This leads to potential subtle differences in approach. 13 Collective references the aggregate of individual instances of recollection and not a measure that goes beyond that. 12 39 Brett Mullins/Volume 1 (2013) in a state of partial or full recollection.14 To echo the criticisms above, what differentiates those who have undergone recollection from those who have yet to complete the concept formation? Again, this suggests that there exists a second-order uncertainty among recollecting agents regarding whether or not they have attained full recollection. From this uncertainty, a skepticism emerges obscuring those with full knowledge from those with partial knowledge. This skeptical argument from second-order uncertainty is of the same form as that regarding the short-term formulation of recollection considered above. If the present argument is the only charge against this second formulation of recollection, then partial recollection could hardly be dismissed, since it accounts for the apparent conflict and uncertainty among epistemic agents. On this interpretation, one who forms a judgment regarding an absolute idea is either in a state of partial or full recollection, and the second-order uncertainty disables differentiation between those with full knowledge and those with partial knowledge; thus, any knowledge attribution is such that the agent attains only partial or fallible knowledge. Whereas with the short-term formulation the uncertainty rests with the distinction between those who know and those who do not know, with the long term formulation the uncertainty rests with the distinction between those who possess certain knowledge and those whose knowledge is fallible. In the former case, second-order uncertainty undermines any first-order knowledge attribution such that the skepticism results in a global lack of justification among epistemic agents. In the latter case, however, second-order uncertainty undermines any first-order infallible knowledge attribution. Skepticism emerges in the case of partial recollection since certainty is a criterion of knowledge within recollection. If fallible knowledge from partial recollection is allowed as knowledge, then this theory does not provide the account of absolute ideas that it purports. On the other hand, if partial recollection is wholly dismissed, then short- term recollection and its skepticism remain. Perhaps recollection accounts for all knowledge attainment but not for all concept formation.15 Concepts regarding absolute ideas may be formed by generalization from sense experience; yet, as the 14 Recall that knowledge of an idea must precede the contemplation of that idea. This formulation of recollection is endorsed in Dominic Scott, Recollection and Experience (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007). 15 40 Brett Mullins/Volume 1 (2013) concepts are formed inductively, they do not meet the certainty criterion for knowledge.16 The mechanism of recollection provides an avenue for the attainment of infallible conceptions of absolute ideas. It is “only the Philosopher, who has become puzzled by the confusion and contradictions inherent in our external sources, [that] takes so differently a view of reality.”17 Two methods of concept formation or learning can be distinguished: lower learning, which accounts for ‘ordinary knowledge’ through empiricism, and higher learning, which is concerned with the attainment of extra-sensory absolute ideas through recollection.18 It must be noted that ‘ordinary knowledge’ is a bit of a misnomer, since it is attained through induction and is therefore fallible. With the bimodal theory of concept formation, generalization from sense experience brings one from a state of ignorance to possessing mundane concepts. It is only through philosophical reflection and recollection that one progresses from holding mundane concepts to infallible knowledge. This is to say that “gaining this sort of knowledge–knowledge which enables us to call two sensible particulars equal–is a process of reflection. It is impossible to gain knowledge of equality only through the senses. Some additional reasoning must take place.”19 The bimodal theory is distinct from long term or partial recollection in so far as it both provides a separate method for and does not attribute knowledge to the formation of mundane concepts. The bimodal theory can be understood, instead, as a compliment to the short-term theory of recollection. If contending judgments are result of conflicting mundane concepts, then the uncertainty, which has hitherto plagued the analysis of recollection, is potentially accounted for. Philosophers can be distinguished from other epistemic agents in that they are those who partake in higher learning; yet, to recollect, philosophers must encounter sense perception corresponding to an absolute quality. This is to say that philosophers are among the set of those that undergo lower learning but are distinct in that they acquire knowledge through higher learning as well. Concepts formed through lower learning are fallible; though, the possibility exists that the fallible lower concepts correspond to the higher infallible ideas. Such a correspondence is no mere coincidence. The connection between an 16 Elizabeth Laidlaw-Johnson, Plato’s Epistemology: How Hard is it to Know? (New York: Peter Lang Publishing, Inc., 1996), 20-1. 17 Dominic Scott, Recollection and Experience, 19. 18 While similar, this notion of higher and lower learning is distinct from the notion presented in The Republic. For this characterization, see Elizabeth Laidlaw-Johnson, Plato’s Epistemology: How Hard is it to Know? (Bern: Peter Lang, 1996), 15-18. 19 Elizabeth Laidlaw-Johnson, Plato’s Epistemology: How Hard is it to Know?, 21. 41 Brett Mullins/Volume 1 (2013) absolute idea and the material instance of the quality is ontological rather than epistemological.20 It is the philosopher that transcends the apparent conflict of lower learning and undergoes recollection to attain knowledge. The observed conflict is solely the result of the judgments of lower learners contending among themselves and with the judgments of philosophers. If this is the case, then the observed conflict can be dismissed as not being relevant to knowledge. With this conflict removed, the threat of uncertainty and ensuing skepticism among philosophers is extinguished. This conclusion rests on the assumption that all philosophers are in agreement. If there exists contending judgments among philosophers, then the potential for second-order uncertainty and skepticism arises once more. If recollection yields knowledge of absolute ideas and philosophers are those who recollect, then philosophers must be in agreement; to do otherwise is a contradiction. It is apparent, however, that this is not the case. Philosophers with conflicting belief sets cannot both have recollected the same absolute idea and be justified in their judgments.21 It is either the case that this inquiry ends in the impossibility of contradiction or that not all of those, who were supposed to be philosophers, are in fact philosophers. The established criterion for demarcating the philosopher from others is that only the philosopher has undergone recollection. Among the supposed philosophers who hold contending judgments, an uncertainty exists regarding which agent is a philosopher and which is not. Any further attempt to distinguish the philosopher from the set of lower learners is potentially ad hoc and fails to extinguish the apparent uncertainty. Perhaps the relationship between recollection and philosophers is more complex than its characterization as a short-term mechanism. Any formulation of recollection as a mechanism beyond the short term is subject to the above criticism against partial recollection. This is to say that a formulation of recollection as revisionary results in a second-order uncertainty regarding knowledge attributions and, subsequently, reduces any first-order attribution to being fallible. Since a criterion for knowledge is certainty, any long-term formulation of recollection results in skepticism. The difference between partial and bimodal formulations is that in the latter consideration the uncertainty associated with long-term 20 Dominic Scott, Recollection and Experience, 68-9 This assumes that each of the epistemic agents in question employ valid inferential reasoning. It may be argued that it is more likely that the agents have erred in the formation of their respective judgments; however, the point at hand is concerned with the possibility of contradiction rather than the probability. 21 42 Brett Mullins/Volume 1 (2013) recollection is exclusive to the philosopher; whereas with partial recollection, the criticism extends to any agent that formed concepts of absolute ideas. If the addition of a long-term element to recollection among philosophers fails account for both conflict and the criterion of certainty in the bimodal theory, then this hypothesis must be abandoned. This result, however, is that the bimodal theory continues to be plagued by second-order uncertainty and skepticism. Acceptance of the bimodal theory results in potential contradiction and uncertainty regarding the status of philosophers, which undermines any infallible first-order knowledge attribution. If the theory is dismissed, then short-term recollection and its skepticism remain. In closing, the mechanism of recollection as a method of knowledge attainment does not overcome second-order skeptical worries. As a result, it is not clear, given these assumptions, how one would differentiate the knowledgeable from the unknowledgeable. This obscurity regarding knowledge renders this method not suitable as a theory of knowledge despite the potential explanatory power. Recollection requires strong metaphysical commitments yet fails to both yield a satisfactory theory of knowledge and meet its criterion of epistemological certainty. 43