Are overhead costs strictly proportional to activity?

advertisement

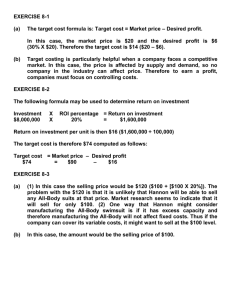

Journal of Accounting and Economics Are overhead to activity? 17 (1994) 255-278. North-Holland costs strictly proportional Evidence from hospital service departments* Eric Noreen INSEAD, Fontainebleau, France University of Washington, Seattle, Naomi WA 98195. USA Soderstrom Universiry of Washington, Received October Seattle, WA 98195, USA 1991, final version received July 1992 Using cross-sectional data from hospitals in Washington State, we test whether overhead costs are proportional to overhead activities. This assumption is at the heart of nearly all cost accounting systems, which implicitly assume that marginal cost is equal to average cost. Empirically, the proportionality hypothesis can be rejected for most of the overhead accounts. On average across the accounts, the average cost per unit of activity overstates marginal costs by about 40% and in some departments by over 100%. Thus, the average cost per activity should be used with a great deal of caution in decisions. Key words: Management functions accounting; Cost behavior; Overhead; Activity-based costing; Production 1. Introduction Cost accounting such as products Correspondence USA. systems typically assign overhead or customers using an averaging to: Naomi Soderstrom, DJ-10, University costs to costing objects process. Turney (1992, of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195, *We would like to thank the staff of the Washington State Department of Health for their able assistance without which this research would have been impossible. We would also like to thank participants in the University of Washington, University of Oregon, and University of British Columbia annual workshop, and Bob Bowen, Jim Jiambalvo, Robert Kaplan, Lauren Kelly, Susan Moyer, Ken Merchant, Chris Stinson, and particularly Dave Burgstahler for their comments. 0165-4101/94/$06.00 0 1994-Elsevier Science Publishers B.V. All rights reserved 256 pp. E. Noreen and N. Soderstrom, 58-59) provides an example Overhead costs and activity in an activity-based costing setting: The cost of the purchasing activity is traced to part numbers via the number of purchase orders per part . . . . A volume of 6,000 purchase orders and an activity cost of $450,000 [for purchasing] yields a cost per purchase order of $75. The cost per purchase order of $75 is clearly an average cost - it is obtained by dividing the total cost of $450,000 by the total activity of 6,000 purchase orders. If this cost of $75 per purchase order is subsequently used in decisions such as whether to drop a product, the implicit assumption is that each reduction in aggregate purchase orders will decrease total purchasing costs by $75. In other words, a decision that reduces total activity by x% will result in a reduction of the associated costs by x%. This is a stronger assumption than linearity; it requires that costs be strictly proportional to activity.’ The proportionality assumption is in conflict with what is commonly believed about economies of scale - average cost should at first decline as volume increases.* Despite the central importance in cost accounting of the assumption that cost is strictly proportional to activity, and its apparent conflict with conventional wisdom in economics, we know of no attempt to empirically test whether the assumption is valid.3 The purpose of this paper is to take the first step in empirically testing whether costs are really strictly proportional to activity in a specific industry. We use a data base compiled by the Washington State Department of Health (WSDOH) from reports submitted by Washington hospitals. The reports contain expense and activity data for predefined overhead cost pools. Our ’ This is not the only assumption about cost behavior that is made when costs generated by typical cost accounting systems are used in decision-making. Noreen (1991) demonstrates that fully allocated costs -even in activity-based costing systems ~ are relevant costs in decisions if and only if the following conditions are satified: 1) all costs can be partitioned into pools, each of which is solely a function of a measured activity; 2) the amount of cost in each cost pool varies in direct proportion to its activity; and 3) all activities can be attributed to products in the sense that if a product is dropped then the activities associated with that product will be avoided. In this paper only the second assumption is examined. Marais (1990) makes similar observations. ’ If average cost decreases with activity, we label this as increasing returns to scale. If average cost is constant and does not depend upon activity, we label this as ‘constant returns to scale’. These definitions are slightly different from the definitions commonly used by economists. 3 Foster and Gupta (1990) examine the relations between overhead spending and various possible measures of activity across 38 facilities of one electronics firm. However, they do not test the proposition that overhead costs are strictly proportional to activity. Kaplan’s (1987) graphs of overhead costs versus various activity measures might be misinterpreted as evidence that there are no fixed costs in the particular firm he studied. However, these are plots of the percentage change in cost veruss the percentage change in activity. There should be no intercept in these plots even if there are substantial fixed costs. On the other hand, if cost is strictly proportional to the activity measures selected, the plots should lie strictly along the diagonal, and most do not. E. Noreen and N. Soderstrom, Overhead costs and activity 251 cross-sectional analyses of the data indicate that most of the overhead cost pools exhibit statistically and economically significant returns to scale; that is, average cost declines with activity. There is an extensive literature concerned with estimating hospital cost functions.4 However, all of these studies have examined the behavior of aggregate hospital costs or of particular medical services. None has dealt with the cost behavior of individual overhead activities. Moreover, these studies have not resulted in any consensus regarding whether there are returns to scale in the provision of medical services in hospitals. Some studies find significant returns to scale and others find none. 2. Testing the proportional cost model Using average costs in decision-making is often justified by the assertion that ‘in the long run all costs are variable’.5 Presumably those who rely on this justification do not necessarily expect spending to be proportional to activity in the short run. Since cost functions estimated with cross-sectional data are interpreted as long-run cost functions [Johnston (1960, pp. 29930)], we base our analysis on cross-sectional data.‘j Thus, we assume that a cost function estimated with cross-sectional data represents the cost expansion path a hospital overhead account would take as activity changes. There are a number of reasons why this might not be true. Activities carried out by a particular overhead function may not really be the same across hospitals. Different costs may reflect differences in quality. Production functions may differ across hospitals, depending upon what fixed capital was acquired and when it was acquired. Input prices may differ, particularly wage rates in different 4 For reviews of this literature (1969) Mann and Yett (1968). see Cowing, Holtman, and Powers (1983), Feldstein (1974), Hefty s See, for example, Greenwood and Reeve (1992, p. 3 1) and Shank and Govindarajan (1989. p. 29). This justification for fully allocating costs appears to be based on a misinterpretation of economists’ discussions of the production function. In economists’ discussions, the statement that ‘in the long run all costs are variable’ defines what is meant by the long run and is not a statement of fact about the way costs behave. That is, the short run is a period in which the levels of some inputs are fixed and cannot be adjusted and the long run is defined to be a period in which the levels of all inputs can be adjusted. Moreover, a variable input is simply one that can be adjusted. There is not any implication in the economists’ discussions that variable costs are strictly proportional to activity. 6 We use the term ‘cost function’ differently than an economist would. An economist views the cost function as a mapping between output and the least costly means of attaining that output given the production technology and input prices. We view the cost function for an overhead cost pool as simply the empirically observed relation between total cost and its measure ofactivity. This could be, but is not necessarily, the minimum cost to attain that activity level. Nevertheless, it seems reasonable to suppose in most cases that whoever controls a hospital would prefer to run efficient overhead activities such as printing and duplicating since money saved on such secondary activities can be put to use on primary activities. 258 E. Noreen and N. Soderstrom, Overhead costs and activity locations. Some hospitals may appear to have abnormally high or low average costs because of transitory abnormal volume. Hospitals are likely to have different patient populations. And, there are likely to be differences among managers in how they adjust to changes in the level of activity. Despite such problems, cross-sectional empirical analysis of cost behavior is at least a starting point in addressing the fundamental question of whether costs are proportional to activity. Given that cross-sectional data will be used, the next question is the functional form used to estimate the cost function. The proportional cost model assumes a very simple cost function in which cost is strictly proportional to a single measure of activity and there are no other explanatory variables. If Cj is the total cost for hospital j and qj is the activity measure at hospital j for a particular overhead account, the proportional cost model assumes cj = (1) Pj'qj3 where pj is a positive constant for hospital j. To simplify cross-sectional empirical testing, we temporarily impose the restriction that pj is the same for all hospitals, or Cj = (2) p’qj. A simple test of the proportional cost model would involve regressing Cj on qj and then testing whether the intercept is zero. However, as we shall see later, this specification of the cost function results in heteroscedastic residuals. Fortunately, this econometric problem largely disappears if the following logarithmic form is used to estimate the cost function: In (Cj) = In(p) + p In (qj). (3) This cost function is consistent with the generalized Cobb-Douglas production function [Heathfield and Wibe (1987, p. 84)]. The slope coefficient p is the ratio of marginal to average cost.7 And, roughly speaking, p quantifies how much of a given percentage change in volume translates into a percentage change in cost. In this logarithmic form the test of the proportional cost model reduces to a test of whether the slope coefficient /I is 1. A slope coefficient of 1 is consistent with the proportional cost model. A slope of less than 1 is consistent with increasing returns to scale. ’ If C = pq8. then average Or, /I= MC/AC. cost is AC = C/q = pq8- ’ and marginal cost is MC = apqBm’= PAC. E. Noreen and N. Sodersrrom. Overhead COGS and activit) 259 3. The data The Washington State Department of Health (WSDOH) collects standardized cost and operating data from over 100 hospitals located within the state. The standard chart of accounts established by the WSDOH includes 36 predefined overhead accounts. Twenty-two of these overhead accounts are used in this study.’ Each of these accounts is described in the appendix using language taken from the WSDOH Accounting and Reporting Manual. The Standard Unit of Measure (i.e., unit of activity) chosen by the WSDOH for each account is also identified in the appendix. The Standard Units of Measure have been selected by the WSDOH. In most cases we believe that a cost system designer would have difficulty identifying a priori any better single summary measure of activity that can be easily measured. For example, the number of admissions is the Standard Unit of Measure for Admitting and it would appear to be a natural choice for an activity measure in a cost system. (And indeed the subsequent analysis indicates a very strong statistical relation between admissions and admitting costs.) The accounts where the choices of activity measures are most questionable a priori are Data Processing (Gross Patient Revenue), Hospital Administration (Number of FTE Employees), and Public Relations (Total Revenue). Even so, better activity measures for these departments are not obvious without breaking them down into finer cost pools. Hospital controllers have indicated to us that they use the WSDOH chart of accounts and the units of service selected by the WSDOH in budgeting and controlling overhead costs. The WSDOH collects data concerning both actual and budgeted expenses and Standard Units of Measure. One research design issue is whether we should analyze actual or budgeted data. We are concerned with the accuracy of product and other costs that are computed in typical cost accounting systems. Some firms rely on actual cost and activity data to compute product and other costs and some use budgeted cost and activity data. It appears most common, however, to use budgeted costs and activity levels to distribute costs to costing objects - particularly in ABC systems. We analyze .both actual and budgeted data in this study, using budgeted data from 1990 and actual data from 1987. *We were not able to use all 36 accounts for a variety of reasons. Seven of the accounts were not used by any hospital. Five accounts were used by such a small number of hospitals that meaningful cross-sectional analysis was impossible. In addition, the relation between costs and units of service in two accounts, Purchasing and Nursing Inservice Education, were so erratic that they are not reported here. In the case of Purchasing, it appears the problem is that the activity measure was defined to be Total Gross Noncapitalized Purchases rather than a measure such as number of purchase orders processed. We have no explanation for the erratic behavior of the Nursing Inservice Education costs. 260 E. Noreen and N. Soderstrom, Overhead costs and activity We used budgeted data from 1990 because prior to 1989 hospitals in Washington were subject to revenue regulation which created incentives to manipulate budgeted figures.’ The regulations are described in Blanchard, Chow, and Noreen (1986). Briefly, the total allowable revenue for a hospital was its budgeted total cost for the year (plus an allowance for profits in the case of for-profit hospitals), adjusted for the difference between budgeted and actual volume. The adjustment in the allowable revenue assumed that the hospital’s variable costs were a specified percentage of total budgeted costs. Hospitals could effectively escape revenue capping by manipulating the budgeted figures they reported to the WSDOH (then called the Washington State Hospital Commission). The evidence in Blanchard, Chow, and Noreen is consistent with such manipulation of budgeted figures. And the staff of the WSDOH has told us that by the mid-1980s they were aware that hospitals were biasing their budgeted data. Actual data is reported to the WSDOH well over a year after the budgeted data is reported. Consequently, there were not enough observations in the most recent version of the database to use actual data from 1990. As a result, we went back to the year with most observations - which was 1987. While the form of revenue regulation used in the state did not explicitly take into account actual cost data, the staff of the WSDOH reports that by 1987 they were using actual data to check on the budgeted data submitted by hospitals. So it is possible that regulation may have affected actual cost and activity data ~ although it is far from obvious what those effects would have been. At any rate, as we shall see, the results of our tests are remarkably consistent across the 1987 actual data and the 1990 budgeted data samples. If revenue regulation did affect actual costs reported to the state, the effects were not major in terms of the phenomenon we are studying here. Coding and keying errors are a recurrent problem with hospital databases. We screened the data for these sorts of irregularities in two stages. Although the final analysis concerns only budgeted data for 1990 and actual data for 1987, data from 1973 through 1992 were used for screening purposes. In the first stage, the average cost per unit of activity was calculated for every hospital in every year for which data was available. For this purpose, costs were inflationadjusted using the American Hospital Association’s Hospital Market Basket Index. Within each overhead account, observations that were more than 1.645 standard deviations from the mean of the inflation-adjusted average cost were flagged. We then examined the raw time-series data for each hospital to judge whether the flagged observations were obvious data errors that should be deleted or simply extreme observations that should remain in the sample. An example of a time-series flagged for investigation is provided in table 1. This example concerns the actual 1987 data for hospital 84 and account 8670, 9 Interestingly, cost and activity it is largely at the insistence of hospitals that the WSDOH has continued data even after the demise of revenue regulation in 1989. to collect E. Noreen and N. Soderstrom, Table Example of an apparent coding 1 error: hospital Year Expense 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1131 1221 1343 1216 23925 27652 30614 35826 37102 40009 44000 4090 1 53479 57071 61595 “Flagged 261 Ooerhead costs and actiaitr 84, account 8670, 1987 actual data. Units of service 47311 47317 43147 48416 53825 57346 57017 52556 48447 46885 44433 44473 280” 49698 48751 as outlier. Chaplaincy, which had been flagged as an outlier on the basis of an unusually large average cost. Perusal of the time series of the expenses and units of service for this hospital made it obvious that the 1987 units of service had been coded or keyed incorrectly and the observation was dropped. In the second stage of the screening process, we plotted expenses against units of service (i.e., activity) for each account for 1987 and 1990. The few observations that in our judgement were extremely unusual in the cross-section plots were flagged. For each of these observations, we returned to the time-series data and only deleted the observation if it appeared to us to be clearly inconsistent with other data for that hospital and therefore likely to be a coding or keying error. The numbers of observations eliminated via these two screening processes are listed in table 2 for each account. Overall, slightly in excess of 3% of the observations, or 77 in total, were deleted due to apparent coding and keying errors. While not reported in the table, 64 of these were deleted in the first stage of the screening and only 13 in the second stage of screening. Apart from outright coding and keying errors, there is a potential problem with inconsistencies across hospitals in the definition of the Standard Unit of Measure. The WSDOH does sometimes allow hospitals to modify the definition of the Standard Unit of Measure to suit the hospital’s circumstances; although we have been assured by the WSDOH staff that this is a rare occurrence for the accounts examined in this paper. Nevertheless, inconsistencies in the definitions of the Standard Unit of Measure across hospitals may have caused some of the apparent anomalous observations we noticed and may be responsible for some of the remaining variance in average costs across hospitals. 4 1 I I 6 I 0 3 0 1 3 4 1 1 1 1 2 1 0 2 1 4 . 30 72 47 70 58 73 62 70 55 61 60 55 73 51 57 41 32 23 74 43 60 72 8310: 8320: 8330: 8350: 8360: 8430: 8460: 8510: 8520: 8530: 8540: 8560: 8610: 8630: 8650: 8660: 8670: 8680: 8690: 8700: 8710: 8720: Printing and Duplicating Dietary Cafeteria Laundry and Linen Social Services Plant Housekeeping Accounting Communications Patient Accounts Data Processing Admittmg Hospital Administration Public Relations Personnel Auxiliary Groups Chaplaincy Services Medical Library Medical Records Medical Staff Health Care Review Nursing Administration Deleted 1987 actual number Table 2 and keying errors: Original for coding Account Results of screening 30 70 46 66 57 72 56 69 55 58 60 54 70 47 56 40 31 22 72 42 56 71 Remaining of observations 28 68 39 62 48 70 52 67 50 56 57 55 68 47 57 38 31 28 65 37 60 59 Original I 0 2 4 2 4 4 2 0 2 2 2 I 1 0 0 1 I 0 4 3 2 Deleted 1990 budgeted before and after screening. 27 68 39 61 47 70 48 64 48 55 56 55 66 43 55 34 27 26 65 35 58 57 Remaining : z2 4 a $ 9 r% f: z. 2 \ F? R z 3 3 ; 2 h 2 p % 3 E. Noreen and N. Soderstrom. Overhead costs and activity 263 4. The results The first test consist of examining the relation between average cost and the level of activity. If costs are strictly proportional to activity, then average cost should be constant and independent of the level of activity. If there are increasing returns to scale, average cost should decline as the level of activity increases. An example of a plot of average cost versus units of service (i.e., activity) is displayed in fig. 1. This figure illustrates the relation between average cost and units of service for account 8530, Patient Accounts, for 1990 budgeted data. There is an unmistakable negative relation between average cost and units of service; average cost declines as the activity level increases. This pattern is confirmed by the Spearman rank correlation between average cost and units of service, which is reported in tables 3a and 3b. The null hypothesis of no relation between average cost and the level of activity is rejected at the 0.05 level for 10 out of 22 of the overhead accounts for the 1987 actual data and for 13 out of 22 for the 1990 budget data. The next tests involve estimating cost functions for each of the overhead accounts. However, cross-sectional plots of expenses versus units of service Table 3a Descriptive statistics and Spearman rank correlations between 1987 actual data. Average Account N Mean Std. dev. 8310 8320 8330 8350 8360 8430 8460 8510 8520 8530 8540 8560 8610 8630 8650 8660 8670 8680 8690 8700 8710 8720 30 70 46 66 57 72 56 69 55 58 60 54 70 47 56 40 31 22 72 42 56 71 14.85 7.14 3.33 0.50 20.91 6.44 10.36 772.94 524.96 18.86 14.19 54.92 2325.01 10.80 456.92 2.48 2.49 239.74 45.93 798.45 20.28 2230.24 10.94 3.06 1.60 0.16 33.25 2.46 3.52 751.85 184.63 9.76 5.99 30.09 1459.11 8.37 191.24 2.54 “One-tailed probability associated 1.53 142.62 18.19 632.00 12.16 1124.37 average cost Min. Spearman rank corr. i-s Prob(rs) Max. 0.6 1 1.36 1.23 0.25 1.56 3.20 2.36 63.52 129.79 8.24 4.61 15.46 629.94 1.oo 117.51 0.53 0.50 64.94 12.48 63.56 5.27 502.34 with the alternative cost and units of service: 42.03 18.76 9.05 1.23 184.88 19.14 19.91 427 1.65 890.64 54.69 31.42 149.80 8709.94 36.12 9 13.05 16.73 6.32 544.80 88.45 2515.51 61.26 5510.83 hypothesis ~ - - 0.48 0.36 0.14 0.39 0.66 0.03 0.05 0.64 0.21 0.57 0.28 0.21 0.48 0.13 0.04 0.47 0.25 0.01 0.19 0.18 0.35 0.34 that rs c: 1. 0.00 0.00 0.17 0.00 0.00 0.59 0.65 0.00 0.06 0.00 0.99 0.06 0.00 0.19 0.61 0.00 0.08 0.51 0.06 0.12 0.00 0.00 E. Noreen and N. Soderstrom. Overhead costs and activity 264 70 60- El El 50-m z 8 40. 30- b q •I 1 2 0 I 0 I I 200000 100000 300000 units of service Fig. 1. Example of a plot of average cost versus units of service: account 1990 budget data. 8530 (Patient Accounts), Table 3b Descriptive statistics and Spearman rank correlations 1990 budgeted Average Account N Mean Std. dev. 8310 8320 8330 8350 8360 8430 8460 8510 8520 8530 8540 8560 8610 8630 8650 8660 8670 8680 8690 8700 8710 8720 27 68 39 61 47 70 48 64 48 55 56 55 66 43 55 34 27 26 65 3s 58 57 20.08 7.74 3.65 0.52 17.63 7.22 12.91 1001.37 544.62 17.67 14.21 67.83 2596.83 10.67 537.22 2.19 3.33 379.88 59.99 1311.60 29.12 2509.78 13.51 2.86 2.00 0.12 17.76 2.25 4.45 1027.56 170.66 11.11 7.39 38.94 1590.74 6.41 240.67 1.32 2.01 542.54 21.25 1135.16 18.54 1361.48 “One-tailed probability associated between data. average cost Min. Spearman rank corr. YS Prob(rs) Max. 0.41 1.91 1.12 0.25 3.14 2.48 2.92 123.30 188.29 7.42 4.05 23.37 784.95 2.46 110.21 0.37 0.68 8.23 15.23 95.16 3.53 414.93 with the alternative cost and units of service: 43.96 16.64 11.70 0.71 73.40 16.29 28.93 5069.25 911.3s 60.99 37.60 266.20 10494.60 34.00 1307.14 5.62 1.55 2790.90 109.17 4699.19 73.09 5885.12 hypothesis - - - 0.51 0.11 0.15 0.30 0.55 0.20 0.10 0.67 0.44 0.64 0.19 0.30 0.42 0.25 0.20 0.02 0.49 0.06 0.35 0.21 0.37 0.37 that rs < 1. 0.00 0.19 0.19 0.01 0.00 0.95 0.75 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.92 0.01 0.00 0.05 0.92 0.54 0.00 0.61 0.00 0. I 2 0.00 0.00 E. Noreen and N. Soderstrom, 0 100000 Overhead costs and activit) 200000 265 300000 units of service Fig. 2. Example of a plot of expenses versus units of service: account budget data. 8530 (Patient Accounts), 1990 revealed obvious problems with heteroscedasticity. An example of such a plot is displayed in fig. 2. The existence of heteroscedasticity was confirmed by running the GoldfeWQuandt test, the results of which are displayed in tables 4a and 4b. The null hypothesis of homoscedastic residuals was rejected at the 0.001 level for every account in both 1987 and 1990. Taking the natural logs of both expenses and units of service largely eliminated this problem. An example of a plot of log expenses versus log units of service is displayed in fig. 3. The log transform is not entirely ad hoc in the context of estimating cost functions; it has a long tradition in economics and, as previously noted, is consistent with a CobbPDougias production function. The results of running cross-sectional regressions using the log/log form of eq. (3) are summarized in tables 5a and 5b. The independent variable, In(qj), is the log of the units of service for the particular overhead account. The dependent variable, In(Cj), is the log of the expense for that overhead account. The intercept in the regression is an estimate of In(p) and the slope is an estimate of/L Recall that B is the ratio of marginal cost to average cost. If cost is proportional to activity, the slope should be 1. If there are increasing returns to scale, the slope should be less than 1. All but two of the 22 estimates of the slope coefficients are less than 1 for the 1987 actual data and all but three are less than 1 for the 1990 budgeted data. The significance level associated with a one-tailed t-test of the null hypothesis that the slope coefficient b is 1 versus the alternative that it is less than 1 is displayed in the last columns of tables 5a and 5b. The null is rejected at the 0.05 level for 13 of 22 overhead accounts for the 1987 actual data and for 15 of 22 overhead accounts for the 1990 budget data. 266 E. Noreen and N. Soderswom. 11: 7 I * 8 , Ooerhead costs and activit) . 9 I 10 . I . 11 , . 12 , 13 ln(units of service) Fig. 3. Example of a plot of In(expenses) versus In(units of service): account 1990 budget data. 8530(Patient Accounts), Table 4a Goldfeld-Quandt test of heteroscedasticity: Untransformed Account 8310 8320 8330 8350 8360 8430 8460 8510 8520 8530 8540 8560 8610 8630 8650 8660 8670 8680 8690 8700 8710 8720 1987 actual data _____.~ data. Log data R Prob(R) R Prob(R) 32.76 38.21 19.45 34.38 74.83 81.66 246.57 8.43 46.24 13.11 157.32 11.70 9.74 5.32 37.21 2.81 323.75 5.03 116.62 76.66 11.40 32.64 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.01 0.00 0.01 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 2.13 1.22 0.59 0.47 1.34 1.28 1.00 1.35 0.61 0.72 0.89 0.48 0.55 0.34 1.11 0.92 12.11 0.27 1.87 3.70 0.62 0.57 0.07 0.26 0.91 0.99 0.20 0.21 0.50 0.17 0.92 0.83 0.64 0.98 0.98 1.00 0.38 0.58 0.00 0.98 0.02 0.00 0.92 0.97 E. Noreen and N. Soderstrom, 267 Overhead costs and activity One possibility is that units of service may be partially surrogating for the size of the hospital. Smaller hospitals tend to be located in less urban areas and to provide different services than larger hospitals. Therefore, the cost functions of smaller hospitals may be different from the cost functions of larger hospitals. To check on this possibility, we ranked all of the hospitals in our sample on the basis of available beds and created a dummy variable for size which took on a value of 1 for hospitals above the median and a value of 0 for hospitals below the median. The form of the regression equation to control for this factor is In (Cj) = CI+ p In (qj) + yesize dummyj. (4) This is equivalent to allowing In(p) in eq. (3) to take on two values: smaller hospitals and one for larger hospitals: In(p) = a for smaller In(p) = a + q for larger hospitals. one for hospitals, Table 4b Goldfeld-Quandt test of heteroscedasticity: Untransformed Account 8310 8320 8330 8350 8360 8430 8460 8510 8520 8530 8540 8560 8610 8630 8650 8660 8670 8680 8690 8700 8710 8720 1990 budget data data. Log data R Prob(R) R Prob(R) 34.87 22.15 37.01 85.33 12.54 131.17 791.70 14.19 34.58 14.27 121.80 4.14 6.15 11.60 204.75 9.58 30.26 17.37 112.57 152.89 14.09 27.94 0.00 2.04 1.26 0.89 I .03 0.59 1.60 8.28 0.97 1.76 0.63 1.20 0.48 0.55 0.10 0.23 0.61 0.46 0.91 0.06 0.00 0.54 0.07 0.90 0.30 0.98 0.97 0.17 0.88 0.91 0.02 0.66 0.00 0.00 1.00 0.81 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 1.47 0.66 0.53 3.34 0.80 2.42 4.26 0.28 0.73 E. Noreen and N. Sodersrrom, Overhead costs and activity 268 Table 5a Summary of the regressions of log expense on log units of service: 1987 actual Ill(C,)-= @I + data, plll(ijj).a Account adjR2 sig(adjR’) B 8310: 8320: 8330: 8350: 8360: 8430: 8460: 8510: 8520: 8530: 8540: 8560: 8610: 8630: 8650: 8660: 8670: 8680: 8690: 8700: 8710: 8720: 30.7% 81.9% 74.1% 93.1% 54.2% 91.6% 83.5% 43.9% 79.3% 80.2% 85.6% 65.0% 68.9% 44.0% 76.1% 14.8% 42.0% 71.2% 83.3% 53.0% 62.2% 75.1% 0.001 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.008 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.448 0.807 0.884 0.905 0.553 1.002 0.930 0.452 0.924 0.704 1.133 0.910 0.726 0.844 0.996 0.388 0.721 0.950 0.876 0.782 0.782 0.813 Printing and Duplicating Dietary Cafeteria Laundry and Linen Social Services Plant Housekeeping Accounting Communications Patient Accounts Data Processing Admitting Hospital Administration Public Relations Personnel Auxiliary Groups Chaplaincy Services Medical Library Medical Records Medical Staff Health Care Review Nursing Administration Mean slope t(B) ~ ~ - 4.58 4.24 1.49 3.12 6.62 0.07 1.25 8.93 1.18 6.40 2.20 0.98 4.68 I.13 0.06 4.40 1.85 0.39 2.68 1.92 2.61 3.34 df Sk(P) 28 68 44 64 55 70 54 67 53 56 58 52 68 45 54 38 29 20 70 40 54 69 0.000 0.000 0.072 0.002 0.000 0.527 0.109 0.000 0.122 0.000 0.984 0.165 0.000 0.133 0.478 0.000 0.038 0.352 0.005 0.03 I 0.005 0.001 0.797 “sig(adjR*) = significance level associated with the adjR’; r(B) = (1 - /I)/(standard df = degrees of freedom associated with the t-test of /3; sig(b) = one-tailed significance the null hypothesis that fl is I versus the alternative that /? is less than 1. error of p); level under If cost is proportional to activity, but the cost per unit differs for smaller hospitals, the coefficient /I in the regression should be 1 and the coefficient q should be nonzero. As before, however, if there are increasing returns to scale, the coefficient b should be less than 1. The results of the regressions using eq. (4) are reported in tables 6a and 6b. The overall effect of including the size dummy in the regressions is to increase the explanatory power of the regressions and to reduce the estimates of /I. The average value of fl declines from 0.797 to 0.685 for the 1987 actual data and from 0.825 to 0.726 for the 1990 budget data. The null hypothesis of proportionality (i.e., /I = 1) is rejected at the 0.05 level for 14 of the 22 accounts for both the 1987 and 1990 data. The pattern of the q coefficients is interesting. While not all of the q coefficients are significantly different from zero (two-tailed test), nearly all of the coefficients are positive and all of them that are significant are positive. This indicates smaller hospitals have lower marginal costs than larger hospitals (for E. Noreen and N. Soderstrom, Overhead costs and activity 269 Table Sb Summary of the regressions of log expense on log units of service: 1990 budget data, Account adjRZ 8310: Printing and Duplicating 8320: Dietary 8330: Cafeteria 8350: Laundry and Linen 8360: Social Services 8430: Plant 8460: Housekeeping 85 10: Accounting 8520: Communications 8530: Patient Accounts 8540: Data Processing 8560: Admitting 8610: Hospital Administration 8630: Public Relations 8650: Personnel 8660: Auxiliary Groups 8670: Chaplaincy Services 8680: Medical Library 8690: Medical Records 87001 Medical Staff 8710: Health Care Review 8720: Nursing Administration 18.6% 81.3% 76.0% 94.8% 57.4% 91.9% 85.0% 54.2% 84.0% 78.0% 83.8% 73.6% 75.8% 57.8% 84.1% 46.5% 43.2% 44.8% 84.4% 42.1% 61.0% 73.0% Average slope sig(adjR’) 0.014 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 t(B) P 0.324 0.904 0.83 1 0.930 0.657 1.039 0.928 0.47 1 0.816 0.674 1.084 0.842 0.774 0.807 1.112 1.113 0.659 0.959 0.846 0.763 0.812 0.801 - ~ 5.49 1.81 2.25 2.50 4.14 1.06 1.28 9.78 3.56 6.70 1.30 2.30 4.18 1.84 1.71 0.55 2.36 0.19 3.39 1.60 2.20 3.07 df Sk(P) 25 66 37 59 45 68 46 62 46 53 54 53 64 41 53 32 25 24 63 33 56 55 0.000 0.038 0.016 0.008 0.000 0.853 0.104 0.000 0.001 0.000 0.901 0.013 0.000 0.037 0.954 0.708 0.013 0.424 0.00 1 0.060 0.016 0.002 0.825 “sig(adjR’) = significance level associated with adjR*; t(p) = (1 - /I)/(standard error of /I); df = degrees of freedom associated with the r-test of /?; sip(p) = one-tailed significance level under the null hypothesis that /I is 1 versus the alternative that /I is less than 1. the same level of activity in an overhead function) and is consistent with lower wage rates or less intensive or extensive overhead services being offered in the smaller hospitals. How far off are estimates of marginal costs if average costs are used? If the real cost relation is C = pq8, then average cost overstates marginal cost by the percentage (1 - p)/p.‘” The average estimated slope coefficient is on the order of 0.7 in tables 6a and 6b. When the slope coefficient is 0.7, average cost overstates the change in costs resulting from a small change in activity by about 43%. Such errors are large enough to warrant investment in estimating more refined cost functions than the strict proportionality mode1 that is implicit in typical cost accounting systems ~ even activity-based costing systems. ” From footnote 8, if the real cost relationship is C = pqp, then fl = MC/AC. Therefore, if average cost is used to estimate marginal cost, the percentage error is (AC - MC)/MC or (1 - 1)/b. 270 E. Noreen and N. Soderstrom. Overhead COSISand activit) Table 6a Summary of the regressions of log expense on log units of service with a dummy of the hospital; 1987 actual data, In(Cj) = a + p In(qj) + tf size dummyj.a Account adjR’ a 8310 8320 8330 8350 8360 8430 8460 8510 8520 8530 8540 8560 8610 8630 8650 8660 8670 8680 8690 8700 8710 8720 32.8% 83.4% 76.9% 93.3% 64.4% 92.6% 89.7% 49.1% 79.2% 81.7% 85.4% 64.5% 71.6% 46.7% 76.6% 26.2% 40.0% 72.2% 84.7% 51.9% 61.5% 75.4% 7.773 5.778 4.041 1.343 8.798 3.376 5.788 10.616 7.185 7.273 0.713 5.110 10.498 6.303 6.946 9.003 3.670 6.970 6.112 7.698 4.390 9.045 Average fi P 0.372 0.670 0.758 0.845 0.342 0.881 0.703 0.348 0.852 0.578 I.177 0.862 0.545 0.609 0.870 0.189 0.718 0.709 0.752 0.751 0.812 0.729 0.685 9 0.482 0.363 0.443 0.182 0.984 0.340 0.778 0.397 0.172 0.306 0.101 0.099 0.465 0.608 0.284 0.539 0.010 0.823 0.361 0.099 0.069 0.229 r(B) s&(P) 4.79 4.92 2.73 3.45 8.37 2.40 5.06 9.41 1.49 6.07 - 1.85 0.96 5.25 2.08 1.16 5.4 I 1.40 I.31 3.87 1.61 1.34 3.12 0.000 0.000 0.005 0.001 0.000 0.010 0.000 0.000 0.072 0.000 0.965 0.171 0.000 0.022 0.126 OX@0 0.087 0.102 0.000 0.059 0.093 0.002 variable for the size Sk(v) 1.36 2.69 2.53 1.78 4.10 3.34 5.83 2.80 0.96 2.36 - 0.59 0.44 2.74 1.80 1.50 2.62 0.03 1.32 2.69 0.30 - 0.27 1.27 0.186 0.009 0.016 0.080 0.000 0.001 0.000 0.007 0.342 0.022 0.558 0.662 0.008 0.079 0.144 0.013 0.976 0.200 0.009 0.766 0.788 0.210 _ “size dummyj = 1 if hospital j’s available beds is above the median, otherwise 0, t(b) = (I - fi)/standard error of 8; sig(/?) = one-tailed probability level associated with t(b); t(n) = n/standard error of 9; sig(n) = two-tailed probability level associated with t(n). 5. Limitations Several potential limitations should be noted. First, the costs reported by hospitals do not include opportunity costs. Service departments operating at or near capacity impose indirect costs on users in terms of waiting and service degradation and it is possible that total costs (including these indirect and opportunity costs) are strictly proportional to volume even though reported overhead expense is not.” Second, not all hospitals report overhead costs for all overhead accounts. A hospital could omit reporting data for an overhead account either because the I’ Balachandran and Srinidhi (1987) analyze charge-out rates for a service. department with stochastic demand. If users always have the opportunity to go outside the firm for service and if aggregate demand is unrelated to the charge-out rate, a fixed charge-out rate can effectively ration the capacity of the service department in a way that internalizes the externalities caused by users crowding the system. However, the fixed charge-out rate is not equal to the average fixed cost. E. Noreen and N. Soderstrom. Overhead costs and activity 271 Table 6b Summary of the regressions of log expense on log units of service with a dummy of the hospital; 1990 budget data, In(Cj) = a + /I In(qj) + q size dummyj.’ Account adjR’ r 1, 8310 8320 8330 8350 8360 8430 8460 8510 8520 8530 8540 8560 8610 8630 8650 8660 8670 8680 8690 8700 8710 8720 25.5% 82.3% 77.9% 94.8% 65.1% 91.8% 90.2% 55.3% 83.7% 80.4% 83.5% 73.2% 76.5% 57.1% 84.0% 47.1% 42.5% 50.0% 86.5% 43.8% 60.7% 73.0% 10.244 4.700 4.181 0.501 7.876 1.745 6.176 10.504 7.552 7.799 1.822 5.794 9.938 3.422 5.998 0.956 3.017 7.871 7.056 9.238 5.575 9.260 0.142 0.774 0.756 0.91 I 0.462 I.018 0.69 I 0.385 0.798 0.534 1.069 0.808 0.655 0.878 1.043 0.973 0.801 0.586 0.683 0.558 0.726 0.715 Average /? ‘I 0.817 0.307 0.352 0.054 0.847 0.053 0.745 0.255 0.040 0.375 0.038 0.080 0.306 - 0.163 0.171 0.375 - 0.373 1.216 0.429 0.568 0.227 0.241 r(B) 5.92 2.87 3.01 2.00 5.63 - 0.28 4.69 8.08 2.51 6.76 - 0.73 1.75 3.92 0.72 - 0.39 0.11 0.87 1.47 4.90 2.02 1.94 2.73 sig(B) 0.000 0.003 0.002 0.025 0.000 0.610 0.000 0.000 0.008 O.OQO 0.766 0.161 0.000 0.238 0.65 I 0.457 0.197 0.078 0.000 0.026 0.029 0.004 variable for the size f(V) sig(rl) 1.81 2.18 2.04 0.55 3.29 0.42 5.01 1.58 0.28 2.73 0.20 0.40 1.70 - 0.55 0.82 1.16 - 0.82 1.87 3.32 1.26 0.76 1.05 0.083 0.033 0.049 0.584 0.002 0.676 0.000 0.119 0.781 0.009 0.842 0.69 1 0.094 0.585 0.416 0.255 0.420 0.074 0.001 0.217 0.450 0.298 0.726 “size dummyj = I if hospital j’s available beds is above the median, otherwise 0: probability level associated with t(p); r(b) = (I - a)/standard error of /I; sig(/I) = one-tailed t(q) = q/standard error of q; sig(q) = two-tailed probability level associated with t(q). hospital does not carry out the activities associated with that account or because the hospital chooses to include the costs of carrying out those activities in some other account. This is most likely to occur with the smallest hospitals where certain overhead functions may be too small to be reported separately. Consequently, in the accounts where these costs are reported, the total costs of the smaller hospitals may be artificially high. This would produce the appearance of declining average costs in those accounts. This problem is likely to be most severe for account 8610, Hospital Administration, which is used as a catch-all for otherwise unassigned overhead. The other overhead accounts are generally narrowly defined enough so that it would be unlikely that they would be used as a place to report otherwise unassigned overhead costs. Third, it can be argued that even though cost does not appear to be proportional to activity, that is just a symptom that the measures of activity are misspecified. This can be viewed as an errors-in-variable problem. To the extent that there are errors-in-variables, the slope coefficient will be biased downward 212 E. Noreen and N. Soderstrom, Overhead costs and activity in the regression. There are basically two potential sources of errors of this sort. We - or rather the WSDOH - may have selected the wrong measures of activity. Or, the measure of activity may be correct but is measured with error. For example, an argument can be made that the appropriate measure of activity for overhead accounts should be the activity that could be supported at capacity rather than the actual or budgeted activity. Some overhead costs are likely to be more closely related to the amount of capacity provided than to the amount of capacity used in a particular period. We used actual and budgeted activity rather than activity at capacity in our tests for two reasons. First, measures of activity at capacity were not available to us for these overhead accounts. Second, organizations typically assign overhead costs to products and customers using actual and budgeted activity levels, not activity at capacity. While Cooper and Kaplan (1991, pp. 165-171) and others have argued that costs of providing capacity should be allocated on the basis of volume at capacity, this proposal appears to have been only rarely implemented to date. Nevertheless, it may be true that overhead costs are strictly proportional to the capacity provided in each overhead function. Joseph and Folland (1972) and others have argued on the basis of queuing theory that the percentage of capacity utilization in a hospital should increase with the size of the hospital. Basically, larger hospitals should have more stable demand by virtue of the larger population from which patients are drawn. Therefore, larger hospitals require porportionally less surge capacity to deal with random fluctuations in demands than smaller hospitals. This prediction is borne out by the plot of the percentage of unused capacity versus available beds displayed in fig. 4. The very 80% - % 2 -0 s 60% - 40% 0 3 Q 200 4bo available 6bO 8bO beds Fig. 4. Plot of the % of unused capacity [ = (available beds x 365 budgeted patient days)/available beds x 3651 versus available beds: 1990 budget data. E. Noreen and N. Soderstrom, Overhead costs and activity 273 smallest hospitals (i.e., those with the smallest number of available beds) have very large unused capacity, both absolutely and relative to the larger hospitals. To see the problem this creates, assume that some of the costs of hospitals are directly proportional to available beds; for purposes of illustration, assume it costs $1000 per available bed to provide a particular service. If the log of this hypothetical cost [i.e., ln(lOOO x actual available beds)] were regressed on the log of actual patient days from our sample, the slope coefficient would be 0.66. While, by assumption, the cost is proportional to capacity provided, it is not proportional to the amount of the capacity used. This pattern could exist in the overhead functions we have studied. That is, the smallest hospitals may have proportionally much higher unused capacity in the overhead functions than larger hospitals. Thus, even though costs may be strictly proportional to the amount of capacity provided in an overhead function, a regression of the log of cost on the log of actual or budgeted activity would yield a slope coefficient less than 1. Nevertheless, if we have an errors-in-variables problem, so does anyone who attempts to use actual or budgeted activity levels from the WSDOH chart of accounts to make decisions. Take, for example, a hospital administrator who estimates future admitting costs by multiplying estimated future admissions by the average actual or budgeted cost of admitting per admission. Such a hospital administrator will tend to overestimate total admitting costs when there is an increase in patients admitted and to underestimate total admitting costs when there is a decrease in patients admitted. The final limitation is the practical question of how one would go about estimating a nonproportional long-run cost function for a particular firm in the absence of cross-sectional data. Perhaps account analysis or time-series analysis can be used for this purpose. At any rate, the research agenda for management accounting academics should include further testing of the strict proportionality assumption (and other assumptions inherent in cost accounting systems) and developing and testing of feasible alternatives to averages as a means of estimating costs. 6. Conclusion We use cross-sectional data to estimate the relation between spending and activity for a variety of overhead accounts in hospitals. The hypothesis that overhead costs are strictly proportional to activity, which is implicit in cost accounting systems, is rejected for most overhead accounts. And average costs overstate incremental costs by substantial margins for many of the overhead accounts. It is obviously costly to build more sophisticated cost systems that recognize nonproportional costs structures. Nevertheless, if the hypothesis that costs are 214 E. Noreen and N. Soderstrom, Overhead costs and activity strictly proportional to activity is rejected, some modification to standard cost accounting methods may be advisable if costs are to be decision-relevant. Basically, pro-rating of costs would have to be abandoned since it is this mathematical tool that requires strict proportionality. Instead, the relations between costs and activities could be represented by cost schedules and the cost of a particular activity would be the incremental cost of that activity taken from the cost schedule. This change in cost accounting procedures is not as innocuous as it may appear at first glance. Incremental costs are different from average costs if costs are not strictly proportional. Moreover, incremental cost depends upon the level of activity if the cost function is nonlinear. Appendix Description of accounts, abstracted from Health accounting and reporting manual the Washington The direct expenses under each account include salaries benefits, professional fees, supplies, purchased services, lease, and other direct expenses. Transfer payments from considered as an offset to direct expenses by the WSDOH, in this study. We are interested in the costs of providing whether or not those costs happen to be offset by transfer parts of the organization. Account 8310 Printing and Duplicating This cost center shall contain the direct expenses incurred printing and duplicating center. Standard Unit of Measure: Number of reams of paper State Department of and wages, employee depreciation/rental/ other accounts, while have been excluded an overhead service payments from other in the operation Account 8320 Dietary This cost center contains the direct expenses incurred in preparing ing food to patients. Also included is dietary’s share of common cafeteria. Standard Unit of Measure: Number of patient meals served of the and delivercosts of the Account 8330 Cafeteria This cost center contains the directly identifiable expenses incurred in preparing and delivering food to employees and other nonpatients. Also included is the cafeteria’s share of common costs of dietary. Standard Unit of Measure: Equivalent number of cafeteria meals served E. Noreen and N. Soderstrom. 275 Overhead COSISand aciivit] Account 8350 Laundry and Linen This cost center shall contain the direct expenses incurred in providing laundry and linen services for hospital use, including student and employee quarters. Costs of disposable linen should be recorded in this cost center. Standard Unit of Measure: Number of dry and clean pounds processed Account 8360 Social Services This cost center contains the direct expense incurred in providing to patients. Standard Unit of Measure: Number of personal contacts social services Account 8430 Plant This cost center contains the direct expense incurred in the operation hospital plant and equipment. Standard Unit qf Measure: Number of gross square feet of the Account 8460 Housekeeping This cost center contains the direct expenses incurred by the units responsible for maintaining general cleanliness and sanitation throughout the hospital and other areas serviced (such as Student and employee quarters). Standard Unit of Measure: Hours of service Account 8510 Accounting This cost center shall include the direct expenses incurred in providing general accounting requirements of the hospital. Standard Unit of Measure: Average number of hospital employees the Account 8520 Communications This cost center shall include the direct expenses incurred in carrying on communications (both in and out of the hospital), including the telephone switchboard and related telephone services, messenger activities, internal information systems, and mail services. Standard Unit of Measure: Average number of hospital employees Account 8530 Patient Accounts This cost center shall include the direct expenses incurred in patient-related billing activities and in extending credit and collecting accounts. Standard Unit of Measure: Gross patient revenue Account 8540 Data Processing This cost center shall contain the costs incurred in operating an electronic data processing center. Expenses incurred in the operation of terminals of the EDP 216 E. Noreen and N. Sodersrrom, Overhead COSISand activily center throughout the hospital shall be included in the data processing cost center. However, outside service bureau costs directly chargeable to a specific nursing or ancillary cost center should be included in that specific cost center. Outside service bureau costs benefiting more than one cost center shall be included in the data processing cost center. Standard Unit of Measure: Gross patient revenue Account 8560 Admitting This cost center shall include the direct expenses general inpatient admitting offices. Standard Unit of Measure: Number of admissions incurred in operating all Account 8610 Hospital Administration This cost center contains the direct expenses associated with the overall management and administration of the institution, including the office of administrative director, governing board, and planning activities. Also expenses which are not assignable to a particular cost center should be included here. However, care should be taken to ascertain that all costs included in this cost center do not properly belong in a different cost center. Standard Unit of Measure: Number of FTE employees Account 8630 Public Relations This cost center contains the direct expenses incurred in the public relations/community relations function and expenses associated with fund-raising. Standard Unit of Measure: Total revenue Account 8650 Personnel This cost center shall be used to record the direct expenses out the personnel function of the hospital. Standard Unit of Measure: Number of FTE employees Account 8660 Auxiliary Groups This cost center contains the direct expenses hospital auxiliary or volunteer groups. Standard Unit of Measure: Number of volunteer incurred incurred in carrying in connection with hours Account 8670 Chaplaincy Services This cost center contains the direct expenses incurred in providing chaplaincy services and in maintaining a chapel for patients and visitors. It does not include those services as defined in ‘Social Services’. Standard Unit of Measure: Number of hospital patient days E. Noreen and N. Sodersrrom, Overhead Account 8680 Medical Library This cost center contains the direct expenses incurred in maintaining library. Standard Unit of Measure: Number of physicians on active staff Account 8690 Medical Records This cost center contains the direct expenses medical records function. Standard Unit of Measure: Number of inpatient total emergency room and clinic visits 277 costs and actkit.) incurred admissions a medical in maintaining plus one-eighth the of Account 8700 Medical Staff This cost center contains the direct expenses associated with the medical staff, such as the salary of the chief of the medical staff, as well as the salary and other costs associated with a house medical staff which serves in the daily hospital services departments. Interns’, externs’, and residents’ salaries (or stipends) should not be included here, but rather in the applicable education cost center. Compensation paid to chiefs of services as well as other physicians working in ancillary departments should not be included here, but rather in the applicable ancillary cost center. Standard Unit of Measure: Number of physicians on active staff Account 8710 Health Care Review This cost center shall contain the costs incurred in providing peer review, quality assurance, utilization review, professional standards review, and medical care evaluation functions. Standard Unit of Measure: Number of inpatient admissions Account 8720 Nursing Admiuistmtion This cost center shall contain the direct expenses associated with nursing administration. The salaries, wages, and fringe benefits paid nursing float personnel shall be recorded in the cost center in which they work. Scheduling and other administrative functions relative to nursing float personnel are considered costs of nursing administration. Standard Unit of Measure: Average number of nursing service personnel References Balachandran, Kashi R. and Bin N. Srinidhi, 1987, A rationale for fixed charge application, Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance 2(N.S.), 151-183. Blanchard, Garth, Chee Chow, and Eric Noreen, 1986, Information asymmetry, incentive schemes, and information biasing: The case of budgeting under rate regulation, The Accounting Review, Jan., l-15. 278 E. Noreen and N. Soderstrom. Overhead cosls and activirq Cooper, Robin and Robert S. Kaplan, 1992, The design of cost management systems: Text, cases, and readings (Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ). Cowing, T.G., A.G. Holtman, and S. Powers, 1983, Hospital cost analysis: A survey and evaluation of recent studies, in: R. Schemer, cd.: Advances in health economics and health services research, Vol. 4 (JAI Press, Greenwich, CT) 257-303. Feldstein, Martin S., 1974, Econometric studies of health economics, in: M. lntriligator and D. Kendrick, eds., Frontiers of quantitative economics, Vol. II (North-Holland, Amsterdam) 337434. Foster, George and Mahendra Gupta, 1990, Manufacturing overhead cost driver analysis, Journal of Accounting and Economics 12, 3033337. Greenwood, Thomas G. and James M. Reeve, 1992, Activity-based cost management for continuous improvement: A process design framework, Journal of Cost Management for the Manufacturing Industry 5, no. 4, 22-40. Heathfield, David F. and Soren Wibe, 1987, An introduction to cost and production functions (Macmillan Education Ltd, London). Hefty, Thomas R., 1969, Returns to scale in hospitals: A critical review of recent research, Health Services Research 4, 2677280. Johnston, J., 1960, Statistical cost analysis (McGraw-Hill, New York, NY). Joseph, Hyman and Sherman Folland, 1972 Uncertainty and hospital costs, Southern Economic Journal, Oct., 267-273. Kaplan, Robert S., 1987, Regaining relevance, in: Robert Capettini and Donald K. Clancy, eds., Cost accounting, robotics, and the new manufacturing technology (Management Accounting Section, American Accounting Association, Sarasota, FL) 27731. Mann, Judith K. and Donald E. Yett, 1968, The analysis of hospital costs: A review article, Journal of Business 41, 191-202. Marais, M. Laurentius, 1990, Process-oriented activity-based costing, Working paper (Graduate School of Business, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL). Noreen, Eric, 1991, Conditions under which activity-based cost systems provide relevant costs, Journal of Management Accounting Research, Fall, 1599168. Shank, John K. and Vijay Govindarajan, 1989, Strategic cost analysis: The evolution from managerial to strategic accounting (Irwin, Homewood, IL). Turney, Peter B.B., 1992, What an activity-based cost model looks like, Journal of Cost Management for the Manufacturing Industry 5, 5460.