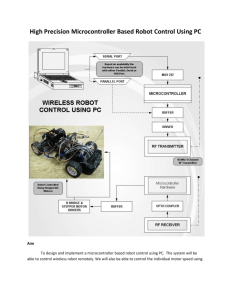

Control Signal Transmission through Power Supply Cables by

advertisement