Charles A. Dice Center for Research in Financial Economics

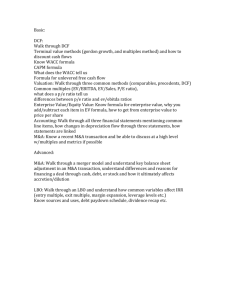

advertisement