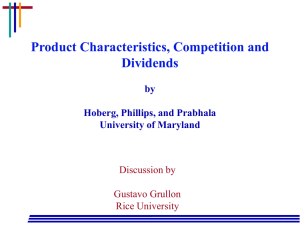

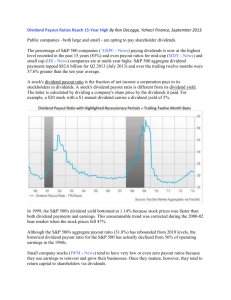

Corporate Payout, Cash Retention, and the Supply of Credit: B

advertisement