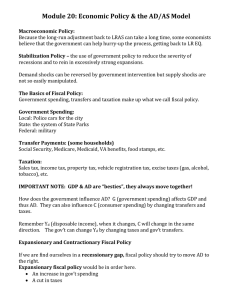

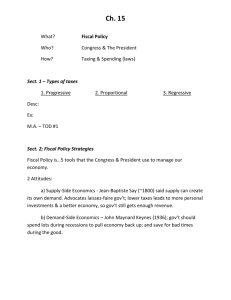

Inequality and Fiscal Redistribution in Middle Income Countries: Brazil, Chile, Colombia,

advertisement