Accounting quality in the corporate bond market Suhas A. Sridharan Stanford University

advertisement

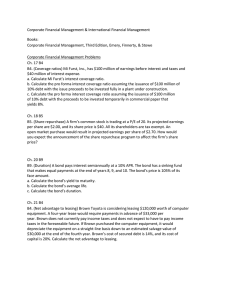

Accounting quality in the corporate bond market Suhas A. Sridharan 1 Stanford University Graduate School of Business February 26, 2013 1 Contact email: sasridh@stanford.edu. Preliminary draft; please do not cite without permission. I would like to thank Mary Barth, Joe Piotroski, Eric So, Kazbi Soonawalla, Maria Ogneva, Stefan Nagel, Peter Demerijian and the participants of the 2011 AAA annual meeting and the Stanford joint finance/accounting seminar for their helpful comments and suggestions. All remaining errors are my own. 1 Introduction In this paper I provide evidence that, in the context of bond valuation, the dimensions of accounting quality that are most relevant are those that describe the quality of firm’s balance sheet disclosures. In measuring information quality, I focus on two balance sheet-based metrics of quality: a measure of asset-side balance sheet conservatism and a measure of the discretionary amount of off-balance sheet debt. I predict and show that these balance sheet-based measures of accounting quality will be more strongly associated with bond yield spreads than are earning-based quality measures such as smoothness and accruals quality. I support this prediction by first demonstrating that the structure of bond payoffs lead bondholders to react differently to equity book value and earnings disclosures. To the extent that book values provide liquidation value estimates while earnings measures abnormal growth opportunities, bondholders will be primarily interested in the former. The predicted dominance of book values in bond valuation is a reflection of the limited upside potential that bondholders face. Unlike equity holders, bondholders do not benefit from improvements in the firm’s profitability beyond the point at which their repayment is ensured. This perspective limits the usefulness to bondholders of information about long term firm performance. Using the Merton (1974) model, I further predict that the relative valuation of book values and earnings is a function of a firm’s default risk. Since debt behaves more like levered equity as default risk increases, debtholders’ relative valuation of earnings will also increase with default risk. A key assumption motivating my hypothesis is that earnings and book values capture fundamentally different pieces of information. Simple observational evidence suggests this is true; the existence of multiple different disclosures - income statement, balance sheet, statement of cash flows, and statement of stockholder’s equity - implies each statement provides information that is incrementally relevant to the rest. Additionally, in the context of equity markets there is substantial evidence that earnings and book values hold complementary valuation roles (Burgstahler and Dichev, 1997; Barth, Beaver, and Landsman, 1998). On the other hand, Easton, Monahan, and Vasvari (2009) argue that earnings information is “the key summary accounting measure” thus making it the primary focus of attention for both equity and debt investors. Additionally, to the extent that earnings provide a better predictor of the future cash flows with which debt payments 1 will be made, one might expect bondholders to find earnings information more relevant than book values. This is especially likely to be true for bonds whose maturities are far into the future. Therefore it remains an open question as to whether the Watts (1974) hypothesis about the dominance of book values in bond markets is accurate. Using a sample of 5,409 corporate bond transactions spanning 1996-2008, I find that the relation between book values and bond yield spreads is stronger than that between earnings and bond yield spreads. This result is robust to the inclusion of controls for bond maturity and credit rating. I also find that bond yields are significantly higher for firms reporting losses or negative book values. I further show that the earnings- debt value relation is mediated by the default risk of the underlying firm. Earnings information becomes more important to bondholders as default risk increases, consistent with their facing a payoff structure similar to that of equity under those conditions. However, book values remain dominant in the bond valuation model. Consistent with these findings, I provide evidence that measures of accounting quality that focus on the balance sheet exhibit stronger and theoretically consistent relations to post-issuance bond yield spreads than earnings-based measures. My results show that corporate bond yield spreads are significantly and positively (negatively) related to a firm’s level of off-balance-sheet debt (reporting conservatism). These relations are directionally consistent with my predictions. In contrast I find no relation between the firm’s level of discretionary accruals and yield spreads and an unpredicted positive relation between yield spreads and earnings smoothness. My findings provide additional support for the hypothesis that the balance sheet is primarily useful for debt contracting and lending decisions while earnings is primarily useful for valuing equity (Watts, 1974). More broadly, I also demonstrate how studying differential stakeholder response to firm disclosures can provide a more robust understanding of accounting information content. In studying the relative valuation of different types of accounting information in debt markets, my paper contributes to both the burgeoning literature on the role of firm specific information on bond pricing as well as the literature on the relative valuation roles of financial information. 2 2 Hypothesis Development s Merton (1973) demonstrate that bondholders’ payoffs can be replicated by holding the firm’s assets and shorting a call option written on those assets. Figure 1 plots the value of debt and equityholders’ claims as a function of equity book value under the assumption of limited liability. Note that the value of equity claims is concave in default risk, while the concavity of the value of debtholders’ claims changes over the range of default risk. Debt claims mimic the behavior of equity claims when default risk is high but become convex when default risk is low. When default seems unlikely, debt payoffs are nearly flat which suggests that the debt market reaction to disclosures should be weak (Fischer and Verrecchia, 1997). Bondholders’ limited liability shields them from both downside risk and upside potential; they can at most expect to receive the face value of their debt claim. This is clearly evident in Equation 1 which provides a simplified expression of expected debt payoffs for a zero-coupon bond: Z Pb = d [1 − F (d|x)] + d R(a, x)f (a|x)da (1) 0 In this expression a designates the firm’s true (unobservable) net asset value, d is the face value of outstanding debt, x is observable accounting information such as book values and earnings, f (a) (F (a)) is the (cumulative) density of expected future net asset value, R(a, x) is the expected recoverable value payable to debtholders under default which is a function of the true net asset value and the observable accounting information. In this model accounting information directly affects investors’ expected distribution of future net asset value (f (a|x)) and the expected recoverable value of debtholder claims R(a, x). These theoretical relations model the empirically documented relations that exist between accounting disclosures and two components of credit risk: probability of default and loss given default (Altman, 2009). Several studies explore the role of accounting information in explaining variation in probability of default. In an early study, Kaplan and Urwitz (1979) demonstrate how financial ratios based on accounting data can be used in a linear model to predict bond ratings. Beaver (1966), Altman (1968), Ohlson (1980), Shumway (2001), Hillegeist, Cram, Keating, and Lundstedt (2004), and 3 Chava and Jarrow (2004) all present predictive models of bankruptcy that incorporate currentperiod financial ratios. The loss given default component of default risk has historically received less attention by researchers though recent work by Amiram (2011) demonstrates that this construct is also predictable using financial ratios. Since default risk is a central component of bond valuation, the documented relation between financial ratios and both components of credit risk suggest a channel through which accounting information will have an impact upon bond prices. However, the inclusion of both balance sheet and income statement ratios in the construction of these models makes it difficult to use these results draw conclusions about the relative informativeness of these two types of information for bondholders.1 Furthermore, there is comparatively little evidence on which attributes of the financial reporting system might matter most in pricing public debt. Beaver, McNichols, and Rhie (2005) shed some light on this question; they find that during a time period when standards evolved to allow increased managerial discretion and more intangible assets there was a decline in the ability of financial ratios to predict bankruptcy. Beaver, McNichols, and Correia (2009) more directly address this issue by demonstrating that the ability of financial ratios to assess distress risk is weaker for firms reporting larger discretionary accruals. Similarly, Ashbaugh-Skaife, Collins, and LaFond (2006) show a positive association between measures of earnings timeliness and accruals quality and firms’ bond ratings. These results are consistent with debtholders being skeptical of managerial discretion in reporting. In contrast to these findings, Amiram and Owens (2010) show that U.S. firms with more discretionary smoothness in earnings experience a lower at- issuance spread on private debt issuances. Taken together these studies suggest a lack of consensus in the literature about what attributes of the financial reporting system generate higher quality information for debt valuation. Moreover, all of the attributes analyzed in these studies are earnings-based, thus leaving unanswered the question of whether accounting quality in the debt valuation context would be more effectively measured by focusing on the balance sheet. Kraft (2010) tangentially addresses balance sheet quality in her discussion of the incentives for and mechanisms by which firms might engage in 1 Beaver, McNichols, and Rhie (2005) note that the most commonly used ratios in these models are return on total assets (typically earnings before interest divided by beginning of year total assets), the ratio of net income before interest, taxes, depreciation, depletion and amortization to total liabilities, and leverage (typically total liabilities divided by total assets). 4 balance sheet management. She notes that firms attempt to avoid consolidation or recognition of off-balance-sheet financing activity in order manage their balance sheets and to report low leverage ratios. Using a sample of corporate bond issuances, she finds at-issue yield spread to be increasing in the level of the firm’s off-balance sheet debt. Also related to my hypothesis is the stream of literature examining accounting quality in the context of debt covenants. Financial reporting is a tool used in debt contracts to minimize the debt-equity conflict by constraining the manager to act in the interest of debtholders. Smith and Warner (1979) outline four sources of agency conflict that debt contracts are used to alleviate. The first source of conflict centers on the asset substitution problem wherein managers acting in the interests of equity investors shift resources towards more risky assets in order to increase equity returns at the cost of increased default risk. Secondly, debt and equity investors might disagree over the decision to increase debt levels since increased debt might increase firm value but decrease the likelihood of debt repayment. Thirdly, there is a conflict of interest between these two stakeholders over dividend payments. Dividend payments are drawn from the same pool of resources used to pay off debt claims so their occurrence is viewed negatively by debtholders. A final conflict arises through the underinvestment problem that emerges as default risk increases and owners face incentive to avoid cash outflows for positive-NPV projects since they anticipate debtholders taking control of the firm in the event of default. By requiring financial reports to meet or exceed certain performance metrics, debt covenants limit the abilities of managers to act outside the interests of debtholders. Armstrong, Guay, and Weber (2010) note that covenants are widely used to address the first three agency conflicts but are considerably less effective at solving the underinvestment problem. In a further simplified version of model 1 where the recoverable value R(a) is equal to the net asset value a, Fischer and Verrecchia (1997) show how the relation between bond value and earnings information is strengthening in default risk, conditional on the default not being so severe as to completely eliminate the possibility of any payment to bondholders. The latter distinction is important because bondholders will once again become insensitive to earnings information if they expect that there will be no proceeds to collect. The predictions of Fischer and Verrecchia (1997) 5 are supported empirically by Plummer and Tse (1999) who show that the earnings-bond return relation is weakening in a firm’s credit rating. Focusing on the differential earnings response of stock and bond prices, Plummer and Tse (1999) also document the concave equity price-earnings relation predicted by Fischer and Verrecchia (1997). Easton, Monahan, and Vasvari (2009) further show that positive earnings news has a smaller impact on bond returns than does negative earnings news, a result they attribute to bondholders’ asymmetric payoffs. Missing from the extant literature on the role of firm specific information in bond pricing is an understanding of financial information other than earnings is reflected in bond values. In choosing to focus on bond return-earnings relation, Easton, Monahan, and Vasvari (2009) claim that earnings are the primary focus of attention for debt investors because earnings is the key summary measure taken from the financial statements. Additionally, to the extent that earnings provide a better predictor of the future cash flows with which debt payments will be made, one might expect bondholders to find earnings information more relevant than book values. This is especially likely to be true for bonds whose maturities are far into the future. Nonetheless, prior research shows that income statement and balance sheet information are incrementally relevant to one another for equity valuation. Collins, Pincus, and Xie (1999) find that the book value of equity is an important correlated variable in the equity price- earnings relation and omitting it results in model misspecification. Ohlson (1995) offers one explanation for this result by providing a model in which equity book value reflects the present value of future normal earnings. An alternative explanation is that equity book value is relevant to price as a measure of liquidation value. This “abandonment option hypothesis” implies that book value will become increasingly important as liquidation becomes more likely. Barth, Beaver, and Landsman (1998) find support for the abandonment option hypothesis by showing that book values become more important for explaining equity value relative to earnings information as a firm’s financial health deteriorates. Burgstahler and Dichev (1997) further show that equity value is a convex function of both earnings and book value and posit that this result is consistent with book value being a measure of abandonment value. Watts (1974) makes an even stronger hypothesis; he argues that as a source of liquidation 6 values, the balance sheet is primarily useful to bondholders and other individuals making lending decisions. Conversely, the income statement is primarily useful for equity valuation. Though the extant relative valuation literature tangentially supports this hypothesis by demonstrating the incremental significance of earnings in equity valuation, the claim that bondholders care primarily about balance sheet information remains untested. If the balance sheet is a source of information on the firm value available to debtholders in the event of default as the equity valuation literature and the Watts (1974) hypothesis suggests, it should be also significantly related to bond price. This leads me to following hypotheses: H1: The relation between book values and bond yield spreads is stronger than that between earnings information and bond yield spreads. H2: The relative valuation of book values and earnings information in bond pricing is a function of a firm’s default risk. H1 is driven by the Watts (1974) hypothesis that balance sheet information is of primary importance to debtholders; if this hypothesis is correct, balance sheet information should always be more important than earnings information in explaining bond value variation. However, to the extent that bondholders behave more like equityholders as default risk increases (Fischer and Verrecchia, 1997), one might expect to observe a shift in bondholders’ relative weighting of balance sheet and income statement information. In particular, as bondholder’s anticipate taking ownership of the firm, we could observe the opposite of what Watts (1974) predicts: a increase in the bond-value relevance of income statement and a decrease in that of the balance sheet. Consequently, I refrain from making a directional prediction in H2. The extant literature identifies specific attributes of the financial reporting system that make accounting information more useful for debt covenant purposes. Zhang (2008) provides a detailed explanation of how conservative reporting benefits lenders through the acceleration of covenant violations, with the resulting transfer of control rights from borrowers to lenders enabling lenders to reduce their risk. Consistent with this prediction, Ball, Robin, and Sadka (2008) demonstrate that the financial reporting systems of countries where debt markets are more important sources 7 of capital exhibit greater conservatism. Borrowing from this literature, preliminary studies on debt valuation have also focused on timeliness and other measures of conditional conservatism as measures of accounting quality in attempting to understand how information quality affects debt pricing. Wittenberg-Moerman (2008) finds the asymmetric timeliness of earnings to be associated with lower bid-ask spreads in the secondary syndicated loan market. However, debt contracting and valuation are likely to demand different information characteristics since they are fundamentally different processes. Therefore it is not clear that focusing only on conservatism as the measure of accounting quality is appropriate in my setting. From my first two hypotheses, I anticipate book values to be the primary source of information for investors when forming bond prices. To this end I expect reporting attributes to more effectively measure information quality for debt valuation to the extent that they are centered on the balance sheet. This leads me to my third hypothesis: H3: Attributes of the financial reporting system that measure precision in the balance sheet provide better measurement of accounting quality in the context of bond valuation than do attributes describing earnings. 3 Research Design 3.1 Reporting Attributes To test hypothesis 3, I investigate the relation between corporate bond yield spreads and four measures of accounting quality: smoothness, accruals quality, asset conservatism, and off-balance sheet debt. The former two measures capture attributes of reported earnings while the latter two describe attributes of the balance sheet. 3.1.1 Smoothness If managers use their discretion to smooth earnings for the purpose of creating more representative reported earnings, smoother earnings will be more informative to users in assessing future net asset value. In contrast, if managers use their discretion to induce noise in earnings to facilitate 8 the extraction of private benefits, then smoother earnings will be less informative (Dechow, Ge, and Schrand, 2010). I maintain the former as the null hypothesis and predict a negative relation between smoothness and yield spread. Following Leuz, Nanda, and Wysocki (2003) I measure smoothness as the ratio of cash flow variability to earnings variability. This assumes cash flows are the appropriate reference construct for unsmoothed earnings which is consistent with past research. Higher values of this ratio indicate smoother earnings which I predict will be associated with lowesr yield spreads. 3.1.2 Accruals Quality A common assumption in the earnings quality literature is that earnings that map more closely into cash are more desirable (Dechow, Ge, and Schrand, 2010). Dechow and Dichev (2002) propose and test a measure of earnings quality that separates operating accruals into predicted and discretionary components. The residual from the regression of current accruals on last- period, current-period, and next-period cash flows is an estimate of the discretionary component of accruals; its inverse is a measure of the quality of reported accruals. Francis, LaFond, Olsson, and Schipper (2005) and Beaver, McNichols, and Correia (2009) demonstrate that this measure is associated with recognized interest expense and the informativeness of financial information in bankruptcy prediction. I use the Dechow-Dichev measure (as a percentage of reported net income) to capture the quality of accruals and anticipate a positive relation between this variable and yield spreads. 3.1.3 Asset Conservatism Penman and Zhang (2002) construct a conservatism C-score that is the ratio of estimated reserves to net operating assets. In calculating estimated reserves they focus on inventories, research and development (R&D), and advertising, three accounts for which they claim GAAP accounting standards are less susceptible to managerial discretion. The inventory component is the LIFO reserve, the research and development component is the capitalization of R&D expenditures, and the advertising component is the capitalization of advertising expenditures. This variable measures the extent to which assets are understated on the balance sheet. In the context of debt contracting, 9 a higher C-score is considered an indicator of higher quality financial reporting. Though it is not clear that this interpretation will be true in the debt valuation context, I maintain this as the null hypothesis. 3.1.4 Off Balance Sheet Debt Prior research on the relation between bond yields and off balance sheet debt relies on the net adjustment to debt reported by Moody’s Financial Metrics as a percentage of on- balance sheet debt. Moody’s net adjustment includes capitalizing the operating lease obligation. As an approximation of this measure I use the ratio of operating lease obligations reported in Compustat to the total reported on-balance-sheet debt. I expect a positive relation between a firm’s level of off balance sheet debt and yield spreads as high levels of off balance sheet debt indicate 3.2 Models My tests regarding the roles of financial statements are based on a regression of bond yield spread on one measure each from the balance sheet and income statement: equity book value (BV E) and earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT ). My first set of empirical tests using the following model Yit = β0 + β1 EBITit + β2 BV Eit + γControlsit + it (2) The subscripts i and t denotes firm and fiscal quarter respectively. In equation (2) , Y is either corporate bond yield spread (Y Sit ) or market value of equity (M V Eit ). Y Sit is the value-weighted average yield spread on outstanding bonds for firm i in quarter t. For a given bond, yield spread is the difference between yield to maturity on the bond and the yield on a treasury note of comparable maturity. For each firm-quarter, the yield spread is calculated by averaging the value weighted yield spreads on all bonds that were traded in the 30 day window after the report date. Market value of equity is measured 30 days after the report date. BV E is book value of equity measured as the difference between total assets and total liabilities and EBIT is net income before interest and taxes. Controls include bond age (Age) measured in months since issuance, indicator controls for the instance of reported losses (Loss) and negative book values (N eg), and the interaction of these 10 indicators with EBIT and equity book value, respectively. I follow prior literature in choosing these variables as each has been shown in prior studies to be significantly correlated with corporate bond market prices (Elton, Gruber, Agarwal, and Mann, 2004). I predict that the coefficients on EBIT and BV E will be negative since higher earnings or book values indicates a greater ability to fulfill debt obligations and consequently should result in lower yield spreads. I anticipate Loss and N eg to both be positively related to the yield spread. I also expect the interactions EBIT ∗ Loss and BV E ∗ N eg to have positive coefficients indicating the premium charged by the bond market for these adverse indicators. I aggregate bond-specific variables within a firm-quarter using the arithmetic mean. For example, Age for a given firm quarter is the average bond age across all bonds issued by the firm that are outstanding in that quarter. To control for potential multiplicative scale effects, I deflate all variables by total assets. Equation (2) is used to test hypotheses H1. H1 predicts that the coefficient on and incremental explanatory power of book value of equity is higher than those of earnings. I obtain coefficient estimates for equation (2) using pooled OLS estimation with standard errors clustered by both year and industry (Gow, Ormazabal, and Taylor, 2010). To compare the incremental explanatory power of EBIT and BV E, I employ a Vuong test of non-nested models. Vuong (1985) outlines a likelihood ratio test that allows for direct comparisons of competing models explaining the same dependent variable. The Vuong test is ideal for the purposes of my study because it does not require an assumption on the “true” model of bond market values. For my analyses the two competing models are E Y Sit = β0 + β1 BV Eit + BV it (3) Y Sit = β0 + β1 EBITit + EBIT it (4) H1 predicts that the Vuong Z statistic from the comparison of model (3) to model (4) will be positive and significant. To formally test H2, which predicts that the relative bond-market valuation of balance sheet and income statement information varies with a firm’s financial health, I estimate the following 11 model: Y Sit = β0 + β1 EBITit + β2 BV Eit + β3 Specit + β4 EBITit ∗ Specit + β5 BV Eit ∗ Specit + it (5) In equation (5), Specit is an indicator variable equalling 1 if the firm i had a bond credit rating of BBB- or lower in period t. H2 predicts a significant coefficient on either EBITit ∗ Specit or BV Eit ∗ Specit in equation (5). To test hypothesis H3 I first conduct a descriptive analysis by calculating yield spread across quintile subsamples using each of the four measures of quality. Consistent with prior research, I anticipate yield spreads to be decreasing in the level of a firm’s reporting conservatism and the smoothness of its reported earnings. In contrast I expect yield spreads to be increasing in the level of off balance sheet debt and the magnitude of abnormal accruals. H3 predicts that the two balance sheet measures of accounting quality (the Penman and Zhang (2002) C-score and percentage of off-balance sheet debt) will be more informative for the purpose of bond valuation than earnings measures (smoothness and discretionary accruals). In the context of my analysis this implies that the difference in yield spread between the highest and lowest quintiles of C-score and off-balance sheet debt will be larger than the difference in yield spread between quintiles formed on earnings smoothness or discretionary accrual levels. I evaluate the significance of differences in subsample means using a t-test allowing for unequal variances. I also test H3 using regression analysis. Specifically I estimate the following equations Y Sit = α + β1 AQit + γControls + it (6) Y Sit = α + β1 CScoreit + β2 OBDit + β3 Smoothit + β4 DAit + γControls + it (7) where CScore is the Penman and Zhang (2002) asset conservatism score, OBD is the percentage of discretionary off-balance sheet debt, Smooth is ratio of historical cash flow to earnings volatility, and DA is the level of discretionary accruals predicted using the Dechow and Dichev (2002) model. As controls I include average bond maturity and credit rating. Both models are estimated cross- 12 sectionally using pooled OLS estimation with two-way industry and quarter clustered standard errors ?. In equation 6 AQ is a placeholder for each of the four measures of accounting quality. H3 predicts that CScore and OBD will have more explanatory power for cross- sectional variation in yield spread (Y S) in model 6. It further predicts that in equation 7 the coefficients on and explanatory power of CScore and OBD will subsume those of Smooth and DA. 3.3 Sample I obtain bond price data using secondary-market corporate bond exchange transactions reported on the Mergent Fixed Income Securities Database (FISD). The database provides data from January 1, 1994 to December 31, 2008; consequently, my sample is limited to this date range.2 . The use of Mergent FISD data raises potential selection bias concerns because the data are limited to transactions of U.S. insurance companies. However, as Easton, Monahan, and Vasvari (2009) discuss, there do not appear to be strong biases in the dataset, nor is there a theoretical argument supporting the existence of such a bias in transaction prices. Furthermore, there is not an alternative to the Mergent FISD database for acquiring the necessary bond issue and transaction data prior to 2004. I construct the sample by first identifying all bond transactions on Mergent FISD that occur at least 30 but no more than 60 days after the issuer’s quarterly earnings report date. I require a minimum of 30 days between the report and transaction dates to ensure that the transactions prices reflect the most recent financial statement information. I use a 30-day window to capture bond prices because corporate bonds trade notably less frequently than stocks. Easton, Monahan, and Vasvari (2009) note that the average (median) number of days in a year on which a particular firm’s stock trades is 243 (252) whereas the average (median) number of days in a year that the same firm’s debt trades is 6 (4). This disparity is largely attributed to differences in the investor bases between the two markets. Relative to equity markets, debt markets are dominated by institutional traders who prefer the predictable payoffs and low volatility of bonds. Perhaps because of greater 2 I begin my sample selection procedure using the full range of data available on Mergent FISD. My other selection criteria, particularly those necessary to construct accounting quality metrics, result in a sample that spans 1996 to 2008 13 efficiency in processing information or regulatory constraints, institutions do not trade as often as individuals (Hong and Warga, 2000). I require that coupon structure be available on Mergent FISD and CRSP so that variable rate debt issuances can be excluded from the analysis. Also excluded are convertible and privately placed bonds, bonds issued in foreign currencies, bonds from firms not required to comply with the SEC’s reporting guidelines, and all subordinated debt. I exclude these bonds because their structures do not fit the assumptions underlying my hypotheses. I obtain firm-specific balance sheet and earnings data through Compustat North America’s Fundamentals Annual database and eliminate observations which lack sufficient data to construct the accounting quality variables of interest for my analysis. The final sample consists of 5,409 bond-quarter observations and 1,778 firm-quarter observations. Tables 1 and 2 provide descriptive statistics for my sample. 4 Empirical Results 4.1 Relative valuation Table 3 presents initial estimation results using pooled OLS estimation with standard errors clustered by both year and industry (Gow, Ormazabal, and Taylor, 2010). I estimate equation 2 in multiple stages in order to capture to incremental contribution of each explanatory variable. Panel A provides estimations using the yield spread as the dependent variable. Column I reveals a negative significant relationship between EBIT and yield spread. Column II similarly shows that book values in isolation are significantly related to bond yield spreads at the 1% level. Column III provides summary statistics from the estimation of equation 2 which reveal that when included simultaneously, both book values and EBIT remain significant. The Vuong statistic comparing incremental explanatory powers of models (3) and (4) reveals that BV E has significantly more explanatory power over yield spreads than does EBIT . This is consistent with my predictions and the assumption that book values are more important to the bond market than earnings information. Panel B of Table 3 estimates the same models as Panel A but uses market value of equity as the dependent variable. As in Panel A, the significance of both earnings and equity book value 14 persists in isolation (columns I and II, respectively) and in simultaneity (column III). In contrast to the results of Panel A, Panel B reports a Vuong statistic of -2.90. This is consistent with prior research which finds that earnings information is more equity value relevant than book values. An examination of the coefficients and R2 values of equity book values across Panels A and B of Table 3 provide additional support for hypothesis H1. The R2 of the BV E (EBIT ) model is higher for the yield spread (equity market value) model, which suggests that book values explain more of the variation in the yield spreads while earnings information explains more of the variation corporate yield spreads. Additionally, the coefficients on BV E in Panel A (-6.71 and -5.44) are larger in magnitude than those of Panel B (1.52 and 0.99), suggesting that bond yields are more sensitive to changes in book value than equity prices. Table 4 explores the sensitivity of the relative valuation of book values to the inclusion of additional explanatory variables. Panel A includes the variables bond maturity (M aturity) measured in years since issuance and rating (Rating) measured as a an integer from 0 to 22 that is decreasing in rating strength. I follow prior literature in choosing these variables as each has been shown in prior studies to be significantly correlated with corporate bond market prices (Elton, Gruber, Agarwal, and Mann, 2004). The results of Panel A of Table 4 confirm that these relationships also exist in my sample; both variables load significantly in a regression of bond yield spreads on these controls and pre-interest and tax earnings/book value of equity. However, the inclusion of these variables does not diminish the incremental significance of book value to earnings, as evidenced by the Vuong Z statistic of 2.32 in Panel A. Panel B of Table 4 uses the models from Panel A as a base and adds to it indicator controls for the instance of reported losses (Loss) and negative book values (N eg) as well as the interaction of these indicators with pre-tax earnings and equity book value, respectively. The findings of Panel B show that either incurring a loss or sustaining a negative book value has a significant negative impact on bond prices as indicated by the positive relation between these variables and yield spread. Nonetheless, the inclusion of these variables does not affect the relative valuation of book value to earnings information. 15 4.2 The role of default risk To understand the role of having a speculative rating on the relative valuation of book values/earnings information, I estimate equation 5 which adds the indicator variable Spec to equation 2 and includes interaction terms for Spec with earnings and equity book value. Summary statistics from this estimation are presented in table 5. As predicted by H3, Spec carries a significant coefficient in the yield spread specifications (Panel A). The coefficient on Spec is positive, a reflection of the debt market imposing a premium on riskier firms. When controlling for the incidence of a speculative rating, EBIT remains significant both in isolation and when interacted with the speculative indicator. Moreover, the signs of the coefficients on EBIT and EBIT ∗ Spec have the same direction, suggesting that earnings information becomes more important for explaining yield spread variation as a firm’s credit rating deteriorates. In contrast, after including the speculative indicator the significance of the coefficient on BV E disappears; BV E is only significant when interacted with Spec. However, the Vuong Z statistic comparing the explanatory power of book value to EBIT in the models including Spec and its interactions is positive and significant. Moreover, it is larger than corresponding statistics from models excluding Spec and its interactions. Thus it appears that controlling for the effect of default risk strengthens the result that book values dominate earnings in debt market valuation. Untabulated results reveal that the use of a matched sample of speculative and non-speculative firms does not qualitatively change the latter result. In the equity value specifications (Panel B), both book value and net income carry significant positive coefficients in isolation and when included together. Spec is consistently significant and negative, indicating the equity markets’ unfavorable response to declines in financial health. The interaction of equity book value with Spec is not significantly different from zero. In contrast, the interaction of net income with Spec is significant and negative in both samples. Summing this negative coefficient with the positive coefficient on net income in isolation leads to a much weaker overall coefficient on net income. This result is consistent with prior research as it suggests that the significance of EBIT declines when a firm has a speculative credit rating. However, unlike prior research, my results do not indicate that the incremental significance of equity book value increases with a deterioration in financial health. Furthermore, the Vuong Z statistic comparing book values 16 to EBIT is not significantly different from zero, suggesting a lack of dominance of either model. 4.3 Tests of accounting quality Table 6 presents results of both univariate and regression based analysis of my third hypothesis that balance sheet-based metrics better capture informational quality for debt market investors. Panel A of table 6 contains the mean yield spreads across quality-based quintiles of the sample. Prior research on accounting quality predicts a positive (negative) relation between yield spread and off balance sheet debt and abnormal accruals (conservatism and smoothness). My hypothesis predicts that the difference in yield spread for the quintiles based on balance sheet measures (off balance sheet debt and conservatism) will be larger than the difference for quintiles based on earnings based measures. The results in Panel A of table 6 reveal evidence consistent with this hypothesis. Of the four measures, only the conservatism score exhibits the predicted relation with yield spread and a significant difference in yield spread across low and high quintiles. Although the smoothness variable generates a significant difference in yield spread across quintiles, the direction of the changes in yield spread contradict predictions. In particular, although theory suggests that smoother earnings is of higher quality, firms with smoother earnings exhibit higher yield spreads. This is consistent with the notion that smoother earnings are the result of managerial manipulation and suggest that the debt market views smooth earnings negatively. Consequently it does not appear that these measures effectively capture accounting quality as well as the balance sheet measures for the purposes of debt valuation. To further tests hypothesis 3, Panel B of table 6 presents summary statistics from the estimation of models (6) and (7). Columns I-IV of Panel B present summary statistics from the estimation of model (6) using each of the four quality metrics as explanatory variables. Even in isolation, there is evidence that the balance sheet based metrics provide a better basis for measuring quality; both OBD and CScore carry significant coefficients that are directionally consistent with predictions. That is, higher levels of off-balance-sheet debt (conservative reporting) are associated with higher (lower) yield spreads. In contrast, columns I and II of Panel B reveal that the earnings-based measures of quality either do not have a significant relation to yield spread or exhibit a relation 17 that contradicts theoretical predictions. In particular, there appears to be no relation between the level of discretionary accruals and yield spread. Though there is a relationship between earnings smoothness and yield spread, this relationship contradicts the fundamental assumption driving the use of smoothness as a quality measure. The literature on earnings attributes identifies smoothness of earnings as a desirable attribute for equity investors. However, in the context of debt valuation it appears that smoothness is not desirable as it is associated with higher yield spreads. Column V of the table presents the results from the estimation of model (7) in which all four metrics are used in simultaneity. The significance of the coefficients on the balance sheet variables increases relative to the single-variable models while the coefficient on the smoothness variable exhibits a greatly reduced t-statistic. The discretionary accruals variable continues to exhibit no significant relation with yield spread. The Vuong statistic comparing a model containing CScore and OBD to one containing Smooth and DA as explanatory variables neither supports nor contradicts these results; At 0.77, it is not significantly different from zero. 5 Conclusion This study uses transactions data from the secondary corporate bond market to ascertain the nature of accounting quality in the public debt market and to test the assumption that the balance sheet is of primary use to debtholders. In particular, I test and find support for two distinct hypotheses. First, I demonstrate that the relation between book values and bond yield spreads is stronger than that between earnings information and bond yield spreads . This result is robust to the inclusion of controls for firm size and financial health. Untabulated results reveal that it also holds across bond-maturity based quintile partitions of the sample, suggesting that temporal subordination of debt does not alter the relation. I further show that the relation between earnings and bond prices is mediated by the default risk of the underlying firm; earnings becomes more significant for bondholders as a firm’s credit rating declines. Nonetheless, the incremental significance of book values in debt valuation persists. Secondly, I hypothesize and show that accounting quality metrics which focus on the balance sheet are more informative for debt valuation than earnings-based ones. In particular, I demonstrate 18 that measures of asset-side balance sheet conservatism and off- balance-sheet debt are significantly associated with yield spreads in a predictable fashion; yield spreads decrease with more conservative reporting and increase in the level of unreported debt. In contrast, my results indicate that earnings based measures of quality such as smoothness and abnormal accruals have little or contradictory relations to yield spreads. In total, my results offer support for the Watts (1974) hypothesis that book values are of primary importance to debtholders. My tests also provide preliminary evidence on the nature of accounting quality for the purposes of debt valuation. Though accounting quality in the context of equity valuation is the subject of a vast literature, my results suggest that characteristics of quality for the purposes of debt valuation are not identical to those for equity valuation or debt contracting. Additional research is needed on how debt valuation differs from both equity valuation and debt contracting and what these differences imply for the determination of information quality. 19 References Altman, E. (1968): “Financial Ratios, Discriminant Analysis and the Prediction of Corporate Bankruptcy,” Journal of Finance, 23(4), 589–609. (2009): “Default recovery rates in credit risk modelling: a review of the literature and empirical evidence,” Working Paper. Amiram, D. (2011): “Debt Contracts and Loss Given Default,” Working paper. Amiram, D., and E. Owens (2010): “Earnings Smoothness and Cost of Debt,” Working paper. Armstrong, C., W. Guay, and J. Weber (2010): “The role of information and financial reporting in corporate governance and debt contracting,” Journal of Accounting and Economics, 50, 179–234. Ashbaugh-Skaife, H., D. Collins, and R. LaFond (2006): “The effects of corporate governance on firms credit rating,” Journal of Accounting and Economics, 42(1-2), 203–243. Ball, R., A. Robin, and G. Sadka (2008): “Is financial reporting shaped by equity markets or by debt markets? An international study of timeliness and conservatism,” Review of Accounting Studies, 13, 168–205. Barth, M. E., W. H. Beaver, and W. R. Landsman (1998): “Relative valuation roles of equity book value and net income as a function of financial health,” Journal of Accounting and Economics, 25, 1–34. Beaver, W. (1966): “Financial Ratios as Predictors of Failure,” Journal of Accounting Research, 4, 71–111. Beaver, W., M. McNichols, and M. Correia (2009): “Have Changes in Financial Reporting Attributes Impaired the Ability of Financial Ratios to Assess Distress Risk?,” Working Paper. Beaver, W., M. McNichols, and J. W. Rhie (2005): “Have Financial Statements Become Less Informative? Evidence from the Ability of Financial Ratios to Predict Bankruptcy,” Review of Accounting Studies, 10, 93–122. 20 Burgstahler, D. C., and I. D. Dichev (1997): “Earnings, adaptation and equity value,” The Accounting Review, 72, 187–215. Campbell, J., and G. Taksler (2003): “Equity volatility and corporate bond yields,” The Journal of Finance, 58(6), 2321–2350. Chava, S., and R. Jarrow (2004): “Bankruptcy Prediction with Industry Effects, Market versus Accounting Variables, and Reduced Form Credit Risk Models,” Review of Finance, 8(4), 537–569. Collins, D. W., M. Pincus, and H. Xie (1999): “Equity valuation and negative earnings: the role of book value of equity,” The Accounting Review, 74(1), 29–61. Dechow, P., and I. Dichev (2002): “The quality of accruals and earnings: The role of accrual estimation errors,” The Accounting Review, 77, 35–59. Dechow, P., W. Ge, and C. Schrand (2010): “Understanding earnings quality: A review of the proxies, their determinants and their consequences,” Journal of Accounting and Economics, pp. 344–401. Easton, P. D., S. J. Monahan, and F. P. Vasvari (2009): “Initial Evidence on the Role of Accounting Earnings in the Bond Market,” Journal of Accounting Research, 47(3), 721–766. Elton, E., M. Gruber, D. Agarwal, and C. Mann (2004): “Factors affecting the valuation of corporate bonds,” Journal of Banking and Finance, 28, 2747–2767. Fischer, P. E., and R. E. Verrecchia (1997): “The Effect of Limited Liability on the Market Response to Disclosure,” Contemporary Accounting Research, 14(3), 515–541. Francis, J., R. LaFond, P. Olsson, and K. Schipper (2005): “The market pricing of accruals quality,” Journal of Accounting and Economics, 39, 295–327. Gow, I., G. Ormazabal, and D. Taylor (2010): “Correcting for Cross-Sectional and TimeSeries Dependence in Accounting Research,” The Accounting Review, 85(2), 483–512. Hillegeist, S., D. Cram, E. Keating, and K. Lundstedt (2004): “Assessing the Probability of Bankruptcy,” Review of Accounting Studies, 9(1), 5–34. 21 Hong, G., and A. Warga (2000): “An Empirical Study of Bond Market Transactions,” Financial Analysts Journal, 56, 32–46. Kaplan, R. S., and G. Urwitz (1979): “Statistical Models of Bond Ratings: A Methodological Inquity,” Journal of Business, 52(2), 231–261. Kraft, P. (2010): “Rating Agency Adjustments to GAAP Financial Statements and Their Effect on Ratings and Bond Yields,” Working paper. Leuz, C., D. Nanda, and P. D. Wysocki (2003): “Earnings management and investor protection: an international comparison,” Journal of Financial Economics, 69(3), 505–527. Merton, R. (1973): “The Theory of Rational Option Pricing,” Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science, pp. 141–183. (1974): “On the pricing of corporate debt: the risk structure of interest rates,” Journal of Finance, 19, 449–470. Ohlson, J. (1980): “Financial Ratios and the Probabilistic Prediction of Bankruptcy,” Journal of Accounting Research, 18, 109–131. (1995): “Earnings, book values and dividends in security valuation,” Contemporary Accounting Research, 11, 661–687. Penman, S., and X.-J. Zhang (2002): “Accounting conservatism, the quality of earnings, and stock returns,” Accounting Review, 77(2), 237–264. Plummer, C. E., and S. Y. Tse (1999): “The Effect of Limited Liability on the Informativeness of Earnings: Evidence from the Stock and Bond Markets,” Contemporary Accounting Research, 16(3), 541–574. Shumway, T. (2001): “Forecasting Bankruptcy More Accurately: A Simple Hazard Model,” Journal of Business, 74, 101–124. Watts, R. (1974): “Accounting Objectives,” Working paper. 22 Wittenberg-Moerman, R. (2008): “The role of information asymmetry and financial reporting quality in debt trading: Evidence from the secondary loan market,” Journal of Accounting and Economics, 46, 260–280. Zhang, J. (2008): “The contracting benefits of accounting conservatism to lenders and borrowers,” Journal of Accounting and Economics, 45(1), 27–54. 23 Figure 1: Debt and equity holder claims as a function of firm value under the assumption of limited liability 24 Table 1: Sample composition (a) Sample composition by year Year 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 Total Unique firm-quarter observations Frequency Percent 45 2.53 48 2.7 76 4.27 116 6.52 175 9.84 204 11.47 211 11.87 175 9.84 154 8.66 122 6.86 161 9.06 145 8.16 146 8.21 1778 100.00 Unique bond observations Frequency Percent 144 2.66 160 2.96 234 4.33 326 6.03 442 8.17 571 10.56 676 12.5 552 10.21 451 8.34 397 7.34 556 10.28 481 8.89 419 7.75 5409 100.00 (b) Sample composition by industry Industry Transportation and Warehousing Accommodation and Food Services Administrative and Support and Waste Management Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing and Hunting Arts, Entertainment, and Recreation Construction Health Care and Social Assistance Information Management of Companies and Enterprises Manufacturing Mining Other Services Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services Real Estate and Rental and Leasing Retail Trade Utilities Wholesale Trade Total 25 Unique firm-quarter observations Frequency Percent 72 4.05 33 1.86 14 0.79 4 0.22 39 2.19 90 5.06 29 1.63 198 11.14 3 0.17 809 45.5 121 6.81 6 0.34 11 0.62 23 1.29 251 14.12 16 0.9 59 3.32 1778 100.00 s Unique bond observations Frequency Percent 294 5.44 71 1.31 27 0.5 5 0.09 143 2.64 282 5.21 62 1.15 526 9.72 4 0.07 2369 43.8 393 7.27 20 0.37 24 0.44 34 0.63 965 17.84 53 0.98 137 2.53 5409 100.00 Table 2: Descriptive statistics Variable BVE MVE YS EBIT Age Maturity Rating Spec Loss Neg Smooth DA OBD CScore N 1778 1778 1778 1778 1778 1778 1778 1778 1778 1778 1778 1778 1778 1778 Mean 0.33 0.95 4.74 0.02 3.34 9.54 9.29 0.44 0.09 0.04 0.32 -0.16 0.49 0.06 Std Dev 0.18 0.97 4.25 0.02 2.56 6.92 4.66 0.50 0.29 0.20 0.40 4.68 1.21 0.10 Min -0.37 0.01 0.81 -0.05 0.00 1.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.03 -30.14 0.00 0.00 26 Q1 0.25 0.42 2.67 0.01 1.50 5.00 6.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.12 -0.49 0.06 0.00 Median 0.35 0.71 3.56 0.02 3.00 7.50 8.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.20 0.21 0.14 0.02 Q3 0.45 1.16 5.12 0.03 4.60 11.60 11.00 1.00 0.00 0.00 0.35 0.79 0.32 0.07 Max 0.67 18.41 31.24 0.10 19.00 64.00 23.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 2.55 19.99 8.14 0.55 Table 3: Relative valuation of net income and book value of equity in bond and equity markets Panel A (B) presents coefficient estimates from linear regressions of yield spread (market value of equity) on net income and book value of equity. Y S is the value- weighted yield spread on all bonds that were traded in the 30 day window after the quarterly report date. EBIT is earnings before interest and taxes. BV E is book value of equity as reported by Compustat at the quarterly report date. T statistics are in parentheses. (a) Dependent variable: Yield spread on traded bonds (YS) Intercept EBIT I 5.70*** (11.85) -63.66*** (-5.60) II 6.54*** (10.51) BVE Obs Adjusted R2 1778 0.10 Incremental R2 EBIT Incremental R2 1778 0.19 1778 0.22 II 0.45*** (3.29) 1.52*** (3.91) III 0.14 (1.26) 22.79*** (4.35) 0.99*** (3.59) 1778 0.06 1778 0.25 EBIT BVE Vuong Z statistic 27 0.06 0.09 3.81*** Market value of equity I 0.43*** (4.48) 24.48*** (4.78) BVE Obs Adjusted R2 1778 0.13 EBIT BVE Vuong Z statistic (b) Dependent variable: (MVE) Intercept -6.71*** (-5.79) III 7.28*** (9.79) -54.36*** (-5.50) -5.44*** (-5.83) 0.19 0.03 -2.90*** Table 4: Relative valuation of earnings and book value of equity in debt markets with additional controls The panels below present coefficient estimates from linear regressions of yield spread on earnings before interest and taxes, book value of equity, and a set of controls. The dependent variable is Y S, the valueweighted yield spread on all bonds that were traded in the 30 day window after the quarterly report date. EBIT is earnings before interest and taxes. BV E is book value of equity as reported by Compustat on the quarterly report date. Age is the number of months since bond issuance. Loss is an indicator variable equalling one if the firm reported negative EBIT. N eg is an indicator equalling one if the firm’s book value of equity is negative. T statistics are in parentheses. (b) Maturity, loss, and negative BVE controls (a) Maturity and age controls Intercept EBIT I 3.18*** (4.39) -47.13*** (-4.75) -0.02 (-1.65) 0.26*** (4.81) -4.72*** (-4.94) -0.02* (-1.75) 0.27*** (4.89) III 4.68*** (5.07) -42.11*** (-4.63) -4.00*** (-5.16) -0.02* (-1.84) 0.23*** (4.67) 1778 0.25 1778 0.27 1778 0.30 BVE Maturity Rating II 3.67*** (4.79) Intercept EBIT BVE Maturity Rating Loss Obs Adjusted R2 Incremental R2 EBIT BVE Vuong Z statistic I 2.45*** (4.08) -21.20*** (-3.31) -0.02 (-1.45) 0.25*** (4.77) 2.11*** (4.02) Neg EBIT*Loss 0.03 0.05 2.32** Incremental R2 28 0.03 (0.00) III 3.61*** (5.03) -20.57** (-2.80) -2.80*** (-4.30) -0.02 (-1.61) 0.22*** (4.65) 1.89*** (4.21) 1.63** (2.44) -43.47 (-1.58) -0.06 (-0.01) 1778 0.30 1778 0.34 -3.49*** (-4.31) -0.02 (-1.65) 0.27*** (4.89) 2.02** (2.14) -52.10* (-1.86) BVE*Neg Obs Adjusted R2 II 3.20*** (4.80) 1778 0.26 EBIT BVE Vuong Z statistic 0.04 0.08 6.98*** Table 5: Relative debt valuation of net income and book value of equity with controls for financial health This table presents coefficient estimates from equation (5). The dependent variable is M V B, the market value of all bonds that were traded in the 30 day window after the quarterly report date. EBIT is earnings before interest and taxes. BV E is book value of equity as reported by Compustat at the quarterly report date. Spec is an indicator variable equalling one if the firm has a speculative credit rating (BBB- or lower). All variables are scaled by total assets as of the quarterly report date and are winsorized at 1%. T statistics calculated using two-way cluster robust standard errors clustered by industry and year are in parentheses. *, **, and *** indicate significance at 10, 5, and 1 percent, respectively. (b) Dependent variable: Equity market value (MVE) (a) Dependent variable: Yield spread (YS) Intercept EBIT I 4.01*** (8.74) -25.42** (-2.52) BVE Spec 3.75*** (4.54) BVE*Spec EBIT*Spec -51.39** (-2.98) Obs Adjusted R2 1778 0.21 Incremental R2 II 4.01*** (6.19) -1.84 (-1.40) 5.40*** (4.69) -8.29*** (-3.52) 1778 0.24 EBIT BVE Vuong Z statistic III 4.59*** (5.22) -24.49** (-2.56) -1.64 (-1.25) 5.40*** (4.30) -7.13*** (-3.17) -37.55*** (-3.08) Intercept EBIT I 0.50*** (3.75) 25.91*** (4.96) BVE Spec 0.02 (0.25) BVE*Spec EBIT*Spec -19.43*** (-4.71) 1778 0.29 Obs Adjusted R2 1778 0.21 0.05 0.08 4.07*** Incremental R2 29 II 0.67** (2.25) 1.39 (1.71) -0.25 (-0.97) -0.68 (-1.03) 1778 0.12 EBIT BVE Vuong Z statistic III 0.08 (0.30) 25.24*** (5.04) 1.18 (1.72) 0.30 (1.50) -0.60 (-1.07) -19.74*** (-4.63) 1778 0.24 0.12 0.03 -0.98 Table 6: Regression analysis of accounting quality Panel A presents mean differences in bond yield spreads on quintiles of the sample partitioned using different measures of accounting quality. Panel B presents summary statistics from linear regressions of corporate bond yield spreads on earnings and balance sheet measures of accounting quality. The dependent variable in Panel B is Y S, the value weighted yield spread for each firm-quarter. Smooth is the ratio of the standard deviation in operating cash flows to the standard deviation of earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) over the prior 10 quarters. AccQual is the Dechow-Dichev (2002) measure of accruals quality. OBD is the ratio of off balance sheet operating lease obligations to total reported debt. CScore is the Penman and Zhang (2002) conservatism score. (a) Univariate analyses Variable Smooth DA OBD CScore Q1 0.04 0.05 0.04 0.04 Q5 0.06 0.07 0.04 0.05 Diff -0.02 -0.02 0.00 -0.01 T -6.80 -1.21 0.00 -2.53 p-value 0.00 0.52 0.89 0.01 (b) Regression analyses Intercept Maturity Rating Smooth I 1.35** (2.49) -0.02 (-1.51) 0.27*** (5.74) 1.71*** (10.14) DA II 1.54** (2.43) -0.02 (-1.36) 0.31*** (5.92) III 1.65** (2.43) -0.02 (-1.33) 0.31*** (5.13) -1.59* (-1.80) V 1.54** (2.28) -0.02 (-1.27) 0.28*** (5.70) 2.02*** (5.51) 0.03 (1.37) 0.12*** (3.15) -2.65** (-2.59) 674 0.23 674 0.29 0.01 (0.94) OBD 0.10** (2.79) CScore Obs Adjusted R2 IV 1.65** (2.87) -0.03* (-1.83) 0.33*** (7.05) 674 0.27 674 0.22 674 0.22 Incremental R2 30 Smooth/DA CScore/OBD Vuong Z statistic 0.00 0.01 0.77