Concrete MONASH UNIVERSITY MUSEUM OF ART CONCRETE: MEDIA RELEASE

advertisement

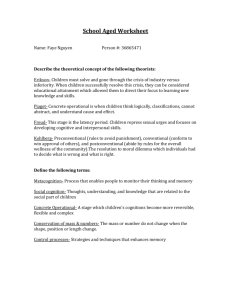

MONASH UNIVERSITY MUSEUM OF ART CONCRETE: MEDIA RELEASE Concrete presented as a key project of 'Australia in Turkey 2015: Celebrating Contemporary Australian Culture' Exhibition dates 29 August – 26 September 2015 Reception: Friday 4 September 2015 Venue Tophane-i Amire Culture and Arts Center / Mimar Sinan Fine Art University Istanbul, Turkey ARTISTS Laurence Aberhart (NZ), Jananne al-Ani (IRQ/UK), Kader Attia (DEU/ DZA), Janet Burchill & Jennifer McCamley (AUS), Aslı Çavuşoğlu (TUR), Saskia Doherty (AUS), Cevdet Erek (TUR), Mekhitar Garabedian (BE/SYR), Fabien Giraud & Raphaël Siboni (FRA), Igor Grubic (CRO), Carlos Irijalba (ESP), Nicholas Mangan (AUS), Rä di Martino (ITY), Ricky Maynard (AUS), Callum Morton (AUS), Tom Nicholson (AUS), Jamie North (AUS), Şener Özmen (TUR), Justin Trendall (AUS) and JamesTylor (AUS) Curator Geraldine Kirrihi Barlow MEDIA For all media enquiries please contact Kelly Fliedner kelly.fliedner@monash.edu +61 418 308 059 Ground Floor, Building F Monash University, Caulfield Campus 900 Dandenong Road Caulfield East VIC 3145 Australia Concrete brings together 22 Australian, Turkish and International artists to explore the concrete, or the solid and its counter: change, and the malleable flow of time. Initially developed to coincide with the centenary of the First World War, the presentation of Concrete in Istanbul comes one hundred years after the first battles at Gallipoli. Concrete considers cycles of construction and destruction, the way civilisations borrow from and build upon each other over time. Monuments and ruins are studied as sites where meaning is condensed whilst also transient, contested and re-writable. Concrete makes a special place for the gaps or absences which stand in for the missing, the experience of loss, and that which is unknown or unknowable. Artworks in the exhibition excavate the complex histories relating to events such as the 1914 destruction of a Russian monument in Istanbul, the deep past of the site of a former weapons manufacturing plant in Guernica, Spain and the demolition of a Sydney incinerator built to echo an ancient Maya temple. Against these solid forms, the passage of time is accentuated­­by the patterns, rhythms and return of changing seasons, the growth rings of an ancient tree, and the fossilised footstep of a dinosaur. Exhibition curator Geraldine Kirrihi Barlow explains, 'Concrete looks to one particular cycle of time, the measure of one hundred years, and sets this against other timespans: the deep time of geology; time as measured by history, literature, monuments and other forms of cultural inheritance; and finally, seasonal time – against which our own lives move so quickly.’ MUMA Director, Charlotte Day comments, 'Concrete considers the function of monuments and ruins from poetic, material and geopolitical perspectives. Also representing MUMA's continued desire to present Australian art and artists within an international context, Concrete builds bridges with university colleagues in Turkey and furthers opportunities for international dialogue. We are thrilled to be able to present Concrete within the historically significant Mimar Sinan designed Tophane-i Amire Culture and Arts Center.' This exhibition has been assisted by the Australian Government through the Australia Council for the Arts, its arts funding and advisory body; and the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade; the Victorian Government through Creative Victoria; the Spanish Government through Spain Arts and Culture; and AsialinkArts. www.monash.edu.au/muma Telephone +61 3 9905 4217 muma@monash.edu Tues – Fri 10am – 5pm; Sat 12 – 5pm Şener Özmen Shut Up! 2014 (detail) c-print courtesy of the artist and Pilot Gallery, Istanbul MONASH UNIVERSITY MUSEUM OF ART CONCRETE: SELECTED ARTWORKS SENER ÖZMEN Şener Özmen draws from the history of the city of Diyarbakır, in southeastern Turkey, where he lives and works. Diyarbakir is a key Kurdish centre, where the recent struggle for a degree of Kurdish autonomy is underpinned by the massive displacement of the Armenian and Kurdish populations in the early twentieth century. Human history in this landscape stretches back to the Neolithic period, and through an extraordinary sequence of civilisations. In Özmen’s work Shut up! a figure lying astride of a concrete edged pit or grave gestures for quiet, as if to silence voices emanating from within the earth. Özmen’s practice is marked by poetry and irony – humour and emotion in the bleakest landscapes. SASKIA DOHERTY Saskia Doherty draws the title of her work Footfalls from Samuel Beckett’s play of the same name, a play in which the central protagonist walks nine steps – a measure of a life – before turning back, and repeating an endless figure eight. From above, her path marks out the mathematical symbol for infinity. Doherty’s Footfalls offers a measured sequence of nine cast concrete steps, like flagstones on a garden path they guide our itinerary through space. Doherty asks us to walk, read and reflect; the rough cement and aggregate of each concrete rectangle bears a cream set of paper, fragments from Beckett’s Footfalls as well as Doherty’s own writing. Doherty also presents an image of Paleontologist Barnum Brown examining the footprints of a Late Cretaceous dinosaur, found as positive counterimpressions in the stone ceiling of a former coal mine – like a distant echo, an imprint of a footprint, embodying the long ago footfalls of an extinct species. Footfalls contrasts transience with permanence, creating a path between brief everyday gestures and longer measures of time. JAMES TYLOR Australian cities and communities feature a wide array of memorials, however the long history of Indigenous Australian occupation is almost entirely absent from such solid forms of public acknowledgement. In Un-resettling James Tylor presents the beginnings of a formal typology of Indigenous dwellings, a number of which relate to his own personal heritage. Tylor states, ‘Un-resettling seeks to place traditional Indigenous dwellings back into the landscape as a public reminder that they once appeared throughout the area.’ Tylor’s photographs remind us of the invisible histories of this land, for instance the fertile volcanic plains west of Melbourne with remnants of stone dwellings and larger ceremonial sites of which there is little public knowledge. LAURENCE ABERHART Photographer Laurence Aberhart is drawn to the edge of dominant historical narratives, creating archives of built and monumental forms particular to certain places and periods of time. He returns to these chosen subjects repeatedly. His photographs of the ANZAC memorials of Australia and New Zealand have been taken over the past thirty years. Familiar across both countries, the memorials were built after the First World War to commemorate those who served with the Australia and New Zealand Army Corps. Very few families were able to visit the graves of those who died, and so these monuments served the bereaved as well as larger national concerns. As we have approached the centenary of the war, these memorials have become the focus of greater attention, yet what they mean is difficult to lock down. In these images the single figure on each column is a fixed point against landscapes in states of constant change. from top: Şener Özmen Shut Up! 2014 c-print, courtesy of the artist and Pilot Gallery, Istanbul Saskia Doherty Footfalls 2013-14 cast concrete, printed paper courtesy of the artist James Tylor Un-resettling (stone footing for dome hut) 2013 hand coloured archival inkjet prints Monash University Collection Laurence Aberhart War memorial, Kaiapoi, Canterbury, 8 December 2010, gelatin photograph, courtesy of the artist and Darren Knight MONASH UNIVERSITY MUSEUM OF ART CONCRETE: SELECTED ARTWORKS JANANNE AL-ANI Jananne al-Ani’s film offers a sequence of aerial views in sepia tones; second by second our perspective nears the ground. Our appreciation of the formal beauty of these images co-exists with our unease as we try to determine what it is we are looking at. Are these archaeological sites, or housing compounds damaged by missile or drone strikes? Iraqi-born al-Ani notes as inspiration the ‘strange beauty’ of Edward Steichen’s 1918 photographs of the Western Front taken whilst he was a member of the US Aerial Expeditionary Force. CARLOS IRIJALBA High Tides (drilling) by Carlos Irijalba presents a 17 metre drilling core from the site of a former weapons factory in the Urdaibai or Guernica Estuary, Basque Country. Beneath an asphalt ‘cap’, layers of soil, clay, limestone and the sedimentary rock Marga are evident. The bombing of Guernica is remembered for its devastating impact upon the civilian population and was the subject of an iconic painting by Pablo Picasso. Irijalba offers a window into the history of this place, as well as longer geological measures of time and materiality. KADER ATTIA In Kader Attia’s photographic series Rochers Carrés we see a series of figures seated on enormous concrete blocks, gazing out across the water to a distant horizon. These are images of possibility as well as constraint. The massive cast concrete forms are like the playthings of giants; their scale suggests they might be the remnants of a vast ancient temple, but the edge of each block is sharp and unweathered by the elements. In fact, these forms are relatively new; they have been placed onto the beaches of Algiers as deterrents to those who might use these sites as disembarkation points for African émigrés. IGOR GRUBIC In the film Monument Zagreb-based artist Igor Grubic offers a series of meditative ‘portraits’ of the massive concrete memorials built by the former Yugoslav state. With the rise of neo-fascism these mysterious sentinel forms, originally intended to honour World War II victims of fascism, are increasingly subject to neglect, even attack. Emphasising the unexpected fragility of these monumental structures, Grubic sets human attempts to fix meaning, against a backdrop of seasonal change. In a landscape which has witnessed so many cycles of trauma and upheaval, this work mirrors the rise and fall of many monuments built to preserve the memory of events which might otherwise be forgotten. Can such forms ever communicate a stable message through time? from top: Jananne al-Ani Excavators 2010 16mm film transfered to video courtesy of the artist Carlos Irijalba High Tides (drilling) 2012 installation view courtesy of the artist Kader Atia Rochers Carrés 2008 five Lambda prints, courtesy of the artist and Galerie Nagel Draxler, Berlin and Cologne Igor Grubic Monument 2014 video projection courtesy of the artist