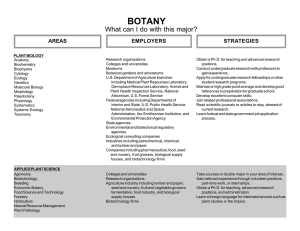

P S LANT CIENCE

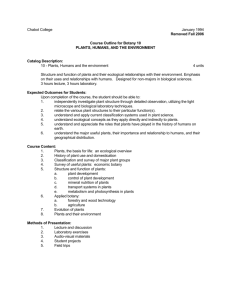

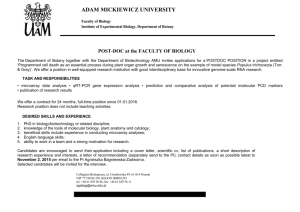

advertisement