PSYCHOMETRIC PROPERTIES OF A MEASURE OF COMPETENCY A DISSERTATION

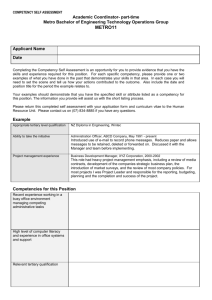

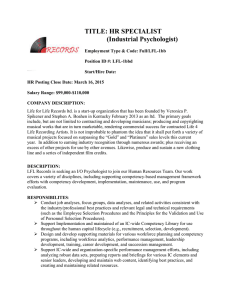

advertisement