QUALITY EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION 1 QUALITY EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION:

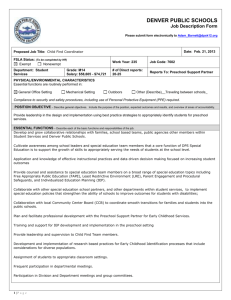

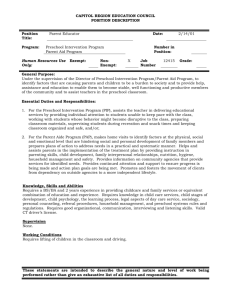

advertisement