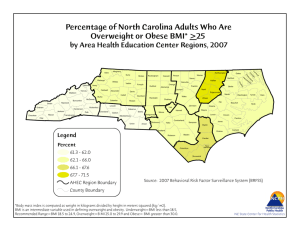

A STUDY TO DETERMINE THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SUGAR- PREADOLESCENTS (11-13 YEARS)

advertisement