NINETEENTH-CENTURY PENNSYLVANIA MENNONITE MEETINGHOUSES IN THE

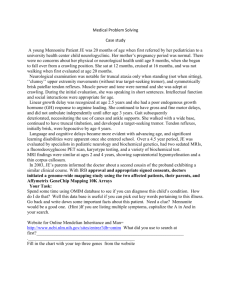

advertisement