WHAT WE TALK ABOUT WHEN AND WHERE WE TALK ABOUT... SOME CULTURAL AND LINGUISTIC FUNCTIONS OF OBITUARIES IN

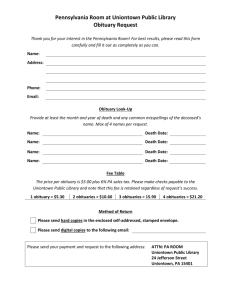

advertisement