Document 10913845

advertisement

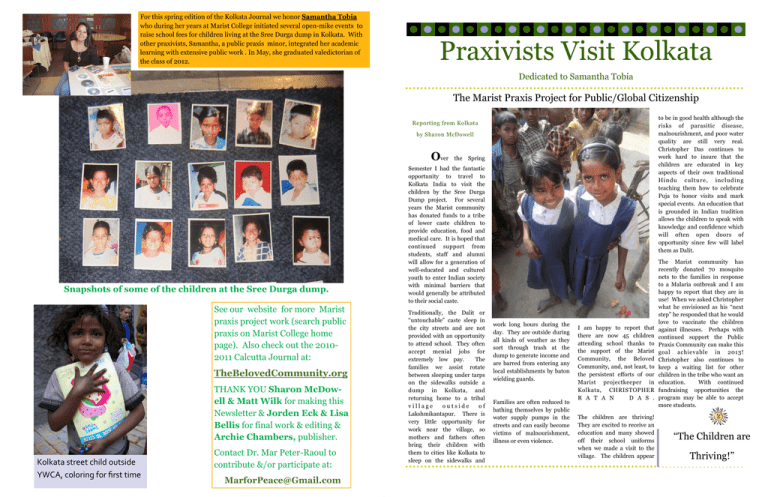

For this spring edition of the Kolkata Journal we honor Samantha Tobia who during her years at Marist College initiated several open-mike events to raise school fees for children living at the Sree Durga dump in Kolkata. With other praxivists, Samantha, a public praxis minor, integrated her academic learning with extensive public work . In May, she graduated valedictorian of the class of 2012. Praxivists Visit Kolkata Dedicated to Samantha Tobia The Marist Praxis Project for Public/Global Citizenship Reporting from Kolkata by Sharon McDowell Over Snapshots of some of the children at the Sree Durga dump. See our website for more Marist praxis project work (search public praxis on Marist College home page). Also check out the 20102011 Calcutta Journal at: TheBelovedCommunity.org THANK YOU Sharon McDowell & Matt Wilk for making this Newsletter & Jorden Eck & Lisa Bellis for final work & editing & Archie Chambers, publisher. Kolkata street child outside YWCA, coloring for first time Contact Dr. Mar Peter-Raoul to contribute &/or participate at: MarforPeace@Gmail.com the Spring Semester I had the fantastic opportunity to travel to Kolkata India to visit the children by the Sree Durga Dump project. For several years the Marist community has donated funds to a tribe of lower caste children to provide education, food and medical care. It is hoped that continued support from students, staff and alumni will allow for a generation of well-educated and cultured youth to enter Indian society with minimal barriers that would generally be attributed to their social caste. Traditionally, the Dalit or “untouchable” caste sleep in the city streets and are not provided with an opportunity to attend school. They often accept menial jobs for extremely low pay. The families we assist rotate between sleeping under tarps on the sidewalks outside a dump in Kolkata, and returning home to a tribal village outside of Lakshmikantapur. There is very little opportunity for work near the village, so mothers and fathers often bring their children with them to cities like Kolkata to sleep on the sidewalks and Caption describing picture or graphic. work long hours during the day. They are outside during all kinds of weather as they sort through trash at the dump to generate income and are barred from entering any local establishments by baton wielding guards. Families are often reduced to bathing themselves by public water supply pumps in the streets and can easily become victims of malnourishment, illness or even violence. I am happy to report that there are now 45 children attending school thanks to the support of the Marist Community, the Beloved Community, and, not least, to the persistent efforts of our Marist projectkeeper in Kolkata, CHRISTOPHER R A T A N D A S . The children are thriving! They are excited to receive an education and many showed off their school uniforms when we made a visit to the village. The children appear to be in good health although the risks of parasitic disease, malnourishment, and poor water quality are still very real. Christopher Das continues to work hard to insure that the children are educated in key aspects of their own traditional Hindu culture, including teaching them how to celebrate Puja to honor visits and mark special events. An education that is grounded in Indian tradition allows the children to speak with knowledge and confidence which will often open doors of opportunity since few will label them as Dalit. The Marist community has recently donated 70 mosquito nets to the families in response to a Malaria outbreak and I am happy to report that they are in use! When we asked Christopher what he envisioned as his “next step” he responded that he would love to vaccinate the children against illnesses. Perhaps with continued support the Public Praxis Community can make this goal achievable in 2013! Christopher also continues to keep a waiting list for other children in the tribe who want an education. With continued fundraising opportunities the program may be able to accept more students. “The Children are Thriving!” Praxivists Visit Kolkata Page 2 Embracing the “View from Below” by Mar Peter-Raoul I am looking at this picture taken by one of the kids living at the Sree Durga dump, a large corner dump in the midst of Calcutta, across from the Sree Durga hotel. The hotel is where I stayed with other members of Philosophers for Peace on my first travel to India. those rare souls such as Dr. Paul Farmer and his Partners in Health colleague, Jim Yong Kim, newly appointed to head the World Bank, that this is a site of privileged perspective, a certain take on the workings of the world, an angle rarely glimpsed in more affluent contexts. The picture is of a mother working in the dump with her 12 year-old-son, their hands sorting through a bag of trash. I imagine they are sorting out specific items to be picked up later by the City, all day work in exchange for an equivalent dollar, or maybe two, depending on the success of their sorting. It is enough for a good meal of rice and a vegetable, but not for much else. Certainly not for school fees for the boy, nor a required uniform, shoes, study materials, and a morning breakfast before school. This “view from below” is almost always missing from corporate board rooms, college curricula, policies made in Washington and other locations of power, and even from a good many religious institutions. Farmer, in Tracy Kidder’s Mountains Beyond Mountains, takes pains to show the interrelationship of the rich and poor. His favorite metaphor is the dam built in Haiti by the U.S. Army of Engineers to bring electricity to the elite in Port-auPrince. The consequences for the poor families farming the very area to be flooded, is catastrophic. With little or no compensation, they are forced to higher, less fertile ground, where they become among Haiti’s poorest. I don’t know which of the kids from the dump took the picture. The minute our team gives them instant cameras to shoot whatever they want, they begin clicking away. We try to keep track when the film is developed - two sets, one for the young photographer and one for our team. We offer to purchase the pictures we like best, managing to like pictures from each set. The kids are very happy with the 100 rupees in each envelope, their very own, which they have earned. We think better than hand-outs, they are earning the rupees. But on further reflection, we realize that they work all the time, rarely receive hand-outs, and do not depend on anyone for their meager earnings. I have to admit to a lifetime of hand-outs – starting with working parents providing food, shelter, clothes, and piano lessons; public schools, a state-subsidized public university, and a grant from Marist College to be here among cast-off, very poor people relegated to the lowest rung of Indian society. It is precisely here that I have learned from my study of liberation and black theology, and from “There are choices made by those in power to make policy, to advance actionable projects, and to prioritize an agenda that over and over Christopher gives new sari to older woman I have a special connection with Kamini, the mother sorting trash with her son. My first time in Calcutta, in my fourth floor walk-up facing the dump, I leaned one night on the sill of the open window drawn to the soft sound of rain. Across the street below, bordering the dump, figures were lifting bundles from the sidewalk where they had been sleeping. The soft rain out my window, was raining on their sleeping cloths, making everything miserably wet. I watched as the figures, carrying their belongings, crossed the street beneath my window, seeking some cover from the rain, unaware of my watching them. One of the mothers lifted a small child onto her hip, and as she crossed the street, seeing me, waved. A sudden current ran through me as I waved back. benefits those who have power” Farmer’s point is that there are reasons for people’s poverty. There are choices made by those with the power to make policy, to advance actionable projects, and to prioritize an agenda that over and over benefits those who also have power. This is true for Haiti; it is true wherever abject poverty exists; it is true for the poor of Calcutta. Though it was my two grandsons, 14 & 16, who while I attended and gave a paper at the Peace Conference, trooped around with the kids at the dump, spending time at night around their little fire and taking pictures, & establishing a friendship that they could not turn their backs on when leaving. This was the beginning of the Calcutta Project. Pictures on these two pages taken by Sree Durga youth (except Christopher giving sari to an older woman.) Spring 2012 Now, my fifth time back to Calcutta, together with Colin, my 14 year-old grandson, now 21, his brother Caleb (17), and Marist students, Sharon McDowell and Lindsay Zambraski, I want to be more present to the dwellers at the dump and come closer to sharing solidarity with them. It isn’t until the second week of this spring break trip to Calcutta, when I get to spend significant time with the families. Today, Christopher, our Calcutta Project-keeper, has packed into taxis 30-40 of the adults and children, bringing them to “the maiden,” a park of stubby grass and a wide open space, with each side bordering a highway. We bring out harmonicas, giving them to a line of 8-11 year old children. Caleb stands in front of them and plays a song inviting them to join him, but they play their own random songs, sliding their mouths side to side. Christopher has spread a large cloth on the ground motioning me to sit there. But first, he sets up a little shrine, and gives me a lei to place on a picture of Mother Teresa. Kamini stays close to me, sharing the cloth as well. Most of the young women have a baby in their arms. Babies are carried everywhere, by everyone. One toddler is crying as she stands at the edge of a tug of war, both teams intense with hilarity and struggle. A teen-ager walking by picks her up and carries her for a while, then sets her down near where he had picked her up. A girl of around 8, near-by, picks up the little girl and runs playing with her. Young children seem always in someone’s arms, with the young men as nurturing as anyone, and young children carrying around even Page 3 younger children. I am reminded of a description of Moses as a nursing father. Before we leave, I give a weathered brass bell to each grandmother. I want to spend more time with them and get to know them, individually, but I feel intolerably hot, and have to leave. I nearly died of heat stroke a few visits ago, and so am wary of staying too long. Kamini takes my arm and shepherds me out of the park. We hug and pause, looking at each other, and smile with affection as we part. A Flood of Memories by Colin-Pierre Larnerd Whenever someone asked how my trip to Kolkata was, I would always have trouble summing up the trip in just a few words. “It was incredible, crazy, awesome, a total sensory overload...” A flood of memories would hit me, but describing everything with a few adjectives just didn’t give the experience justice. After many unsatisfactory explanations of what Kolkata was like, I finally realized that defining a foreign experience in a few words is impossible. It’s just not meant to be and that’s the beauty of traveling to Kolkata. Our team worked with people who are considered the lowest of the low by members of the upper class in Kolkata. This social stratification has been in place for centuries and is deeply embedded in Indian culture. But to our Christopher, Marist Project-Keeper in Kolkata, eating with folks at the dump. He often brings them breakfast, carrying everything himself—bread, bananas & 80 hard-boiled eggs (he boils himself on little one-burner). Page 4 team, these people who lived and worked in a garbage dump were far from the unclean, polluting people that so many others consider them as. Spending time with them made me realize how loving, caring, smart, and cheerful they can be despite their living conditions and place in society. Even though they called themselves Hindus, they were not allowed to enter large temples. Instead, they did their worshipping in front of small shrines scattered throughout the city. I was amazed that they held their faith in a system of belief that indirectly causes their hardships and low social status. Seeing the smiles on the kids’ faces made me realize how our consumer culture makes so many of us dependent on material goods for happiness. Industrialization makes us think we need things when we actually don’t. It was evident that material goods and cash are not necessary for a happy life. They may make things easier or more enjoyable, but love and relationships Praxivists Visit Kolkata between family and friends are what really matters. One experience I will never forget was the time we spent with the kids in their home village. It was so fun playing “king of the hill” with the kids on top of a big mound of dirt they use to create bricks. Another popular activity was playing “tug of war” with everyone. Each game would start off having a few people on each team but every time the game started suddenly half the village would join in on the fun. The chaos was filled with laughter and screams from children grabbing the rope and pulling it one’s own way. I loved how I always ended up being on a team with people from the village. Although we once tried a game between those from India versus those from the U.S., the second Christopher said “Go!” our bond became humanity and team or nationality no longer existed. We played tug of war on our trip to the Bay of Bengal as at the Maiden and village. The energy and enjoyment those children get from something so simple (and dirty) is astounding when you contrast it with affluent children in our country lying around playing video games while complaining about one thing or another. Seeing the squalid conditions these kids are living in makes me realize just how extraordinary it is that they ever smile at all. Those in the dump and village have the most basic of material needs, but in many ways that has led them to grow closer and rely more on each other as a community which is relatively uncommon in the United States. My time in Kolkata was very rewarding and it taught me so much about life in India, the people who live there, and how cultural beliefs can affect so many. The bond between the families and I is one that I truly value. The respect we give one another is mutual and I am thankful that I can call everyone in the dump and village my friend. Lindsay Zambraski, Business major Boy across road with Sree Durga dump in background Mosquito nets donated by Marist faculty & staff Spring 2012 Page 5 The Kolkata Experience by Caleb Larnerd My first visit to Kolkata, Students accompany the Sree Durga families to the Kalighat Temple for a Hindu Ceremony The children are celebrating a Hindu celebration Our arrival is celebrated with a Puja of Welcome! Notice children in their school uniforms The Children of the Sree Durga Dump & the Lakshmikantapur village & Christopher & we praxivists thank you greatly for your support! India was the most memorable trip of my life. While there, I feel as though I got the full Kolkata experience by working with “the untouchables” (people of the lowest caste) and going on many excursions in and around the city. After our long tiring flight we were all awakened with sensory overload as everything was so different. Kolkata is a city that never sleeps and is noisy, smelly, and dirty. You can easily get used to these nuisances, but nothing can prepare you for the poverty in India. Our group stayed in a guest house located near Park St. in the business sector of Kolkata. Here there are more tourists so impoverished people go there to beg. I became friends with many of the homeless people on Park St. as our group would buy them food or items of necessity. Most of the time it’s a lot easier to just give them money instead of having to locate a place they would want to eat at, but we couldn’t be sure our donations were going to their benefit. For example, one night we noticed that a homeless mother of many children, who we had been helping, was acting loopy while on some type of drug. This reinforced our notion of not handing out money, but I felt bad not giving the poor anything when there wasn’t enough time to buy them food. Those situations almost defeated the purpose of our goal to help people in India. My favorite part of Kolkata was traveling to different places around the city. We visited the Kali temple, a park called the Maiden, the Bay of Bengal, a village on the outskirts of Kolkata, the dump where the poorest people we sponsor live and work, and many other places. In the dump and village, I got to know almost all of the people and I loved all the kids, who apparently loved me too. They’d fight over who would hold my hand while walking, talk to me in their language of Bengali as if I understood them, and play fun hand games with me. It’s hard to think that they’re rejected in society and can’t even practice their own religion. This was the reason we went to the Kali temple: so when they entered, their social status wouldn’t be questioned because they were with us. At first I didn’t understand why these lower caste people couldn’t just dress nicer so they could enter places, but I realized there’s another way to distinguish social class in India. Christopher told us about how the families should learn “good manners and appropriate ways to act in Indian culture,” comparing their behavior to higher castes’ Indian manners. I noticed what Christopher was talking about at the Bay of Bengal and the village while we played tug of war with the people. Some would push and shove one another and they wouldn’t listen to Christopher’s directions, pulling on the rope before the game started. Although it was frustrating sometimes, it’s sad that such great people are oppressed in their society because of the way they act. But the way they act is part of their culture and the result of a society that separates them & tells them where they should stay in society. When my friends and family ask me about how my trip to India was, I usually juggle the words awesome, great, and incredible but I can’t give them a good answer to really describe Kolkata. Even while there I switched from taking pictures to videos because I knew photos couldn’t give the experience justice. This is why my adventure in India was so special to me, because so few know what I’m talking about when explaining how much of an eye-opener it was. So few have had the Kolkata experience. Praxivists Visit Kolkata Page 6 Spring 2012 Page 7 A moment of solidarity among women Lindsay, Kamini, Sharon Dipankar is an artist. See his pictures: click Calcutta Journal.on www.thebelovedcommunnity.org, scroll down. A mother and child from the Sree Durga dump visit the Bay of Bengal for the very first time! Picture taken by youth Namaste A brother draws while his sister sleeps A Dalit child begging by the train station. A child stands barefoot inside the dump Project-Keeper Christopher Das breaks into dance