Document 10909456

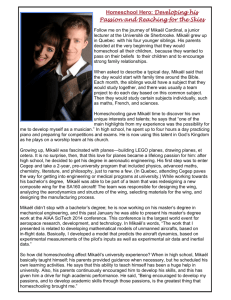

advertisement