Document 10908682

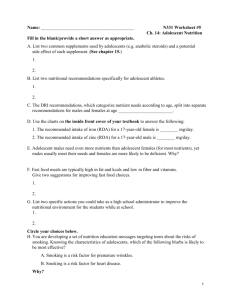

advertisement