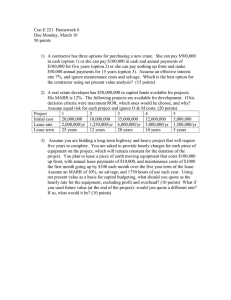

N . C13-0124-1 ________________

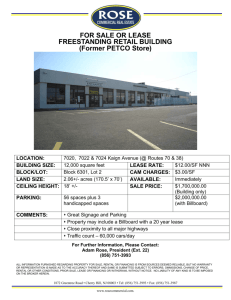

advertisement