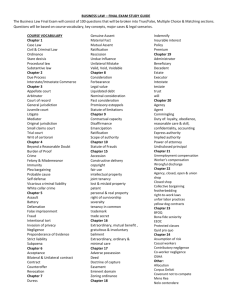

United States Supreme Court I T

advertisement