Integrated Intelligence and Crime Analysis: Enhanced Information Management for Law Enforcement Leaders

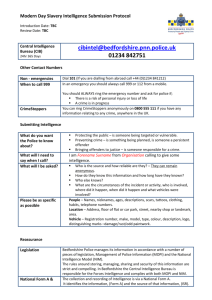

advertisement