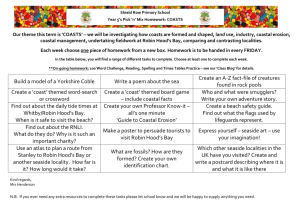

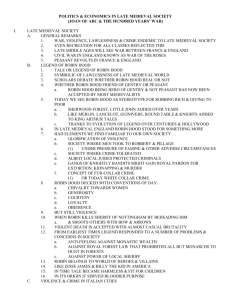

Robin Hood “Under the Greenwood Tree”: Legend

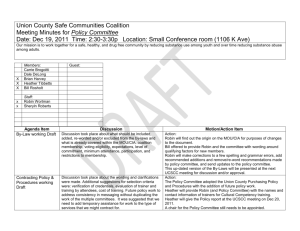

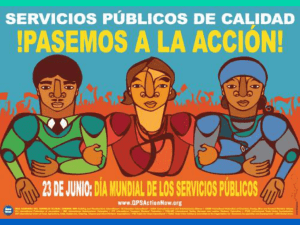

advertisement