Document 10868977

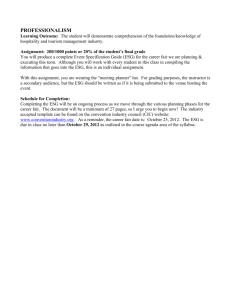

advertisement