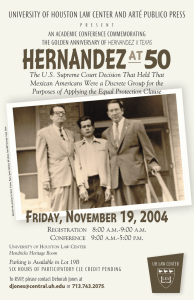

Hernandez v. Texas Kevin R. Johnson

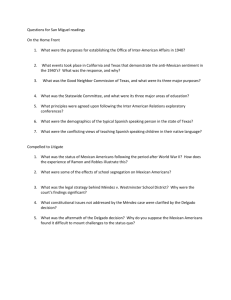

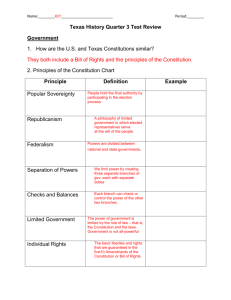

advertisement