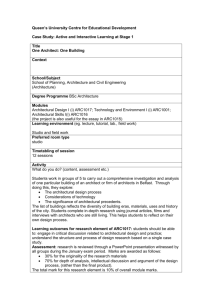

ARCHITECTURAL MEDIATORS: C. B.Arch. Qinghua University

advertisement