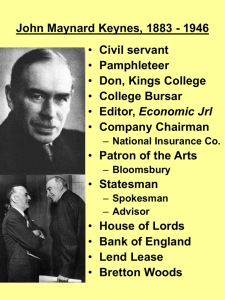

KEYNES AND AUSTRALIA

advertisement