Topic #1: Consumption

advertisement

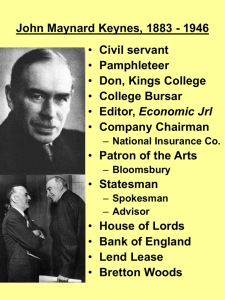

Topic #2: Investment I. Introduction to Concepts Whenever new machines, factories, plant and equipment, tools, and structures are produced and sold, we say that fixed investment has taken place. Sometimes it is as small as a company buying a new light bulb. Sometimes it is as large as the construction of a new production line. Real net fixed investment occurs when there is an increase in existing physical capital. This will happen if gross fixed investment is greater than depreciation. We write this as Real net fixed investment = Gross real fixed investment – real depreciation Sometimes we refer to depreciation as capital consumption allowance. Nominal investment is just real investment multiplied by the price index of investment. Fixed investment does not take place when an existing machine or factory is sold from one owner to another. In that case, we say that there has merely been an exchange of existing assets. Therefore, whenever a person sells corporate stock to another person on the secondary market or stock exchange, this is not investment as economists use the word. It is an sset transfer only. In addition to fixed investment, total investment also includes changes in inventories. For example, if inventories on December 31, 2002 equaled $1000 and if inventories on December 31, 2003 equaled $1100, then annual inventory investment for 2003 equaled to $100. It follows that Total Investment = Total Gross Fixed Investment + Total Inventory Investment and Total Gross Fixed Investment = Total Net Fixed Investment + Depreciation Investment is a flow. It is not a stock, although the amount of capital in the economy is certainly a stock. Investment is the change in this stock of capital. Within a fixed period of time, anything that increases the stock of capital, increases the flow of investment. Investment can be separated into domestic investment and net foreign investment. Net foreign investment represents an increase in foreign capital owned by domestic residents. Investment can also be divided into private investment and public investment. A highway is an example of public capital. Any increase in public capital takes place as public investment. Some countries (e.g., the US) count public investment in G = government spending. public investment in I=total investment. Other countries (e.g., Taiwan) count II. Theories of Investment There are three basic theories of investment that have become popular over the years. The first was introduced by Keynes in the General Theory in 1936. The second was proposed by D. Jorgenson of Harvard during the 1960's and is referred to as the neoclassical theory of investment. The last theory was developed by J. Tobin of Yale and is known as the q-theory. Keynes focused attention on the investment function because he believed that fluctuations in real GDP and employment were mainly due to the unpredictable changes in investment. These unpredictable changes were due to abrupt changes in the psychological expectations of businesses. Keynes felt that the decision to purchase new capital depended on the cost of new capital, the expected stream of future profits expected to be earned by the new capital, and the current long run rate of interest. Anything which affected these three variables could be expected to alter the desire to invest. For example, if prior heavy investment lowered the productivity of potential new capital, this would lower expected profits and thus lower current investment demand. Also, if heavy investment raised the cost of new capital goods, then this would also lower investment. Naturally, a higher real rate of interest would lower real investment. At times, Keynes introduced interesting situations, such as a fall in nominal wage rates, as in Chapter 19. He stated that this would increase investment, but if wage rates were expected to continue to fall, then this would lower investment. The reason for this is that future investment in capital goods would be done at a lower cost and this would mean that current capital would have to compete with future capital requiring a much lower level of profitability. Keynes defined the marginal efficiency of capital (MEC) as the rate of discount that would equate the stream of future expected net revenues from an additional unit of capital with its current supply price. We often write this as: N Pc t 1 E ( Rt Ct ) (1 m e )ct where Rt = revenue and Ct = cost. Keynes felt that confidence would also affect this mec. How could it do this?