INTERNATIONALISATION AND PRICING BEHAVIOUR: SOME EVIDENCE FOR AUSTRALIA

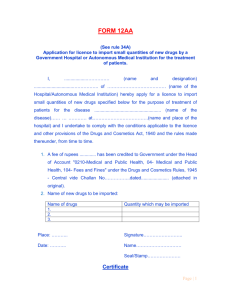

advertisement