AN HIGH VACANCY PHENOMENON STEVEN Y)

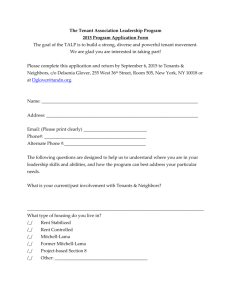

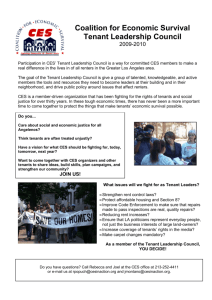

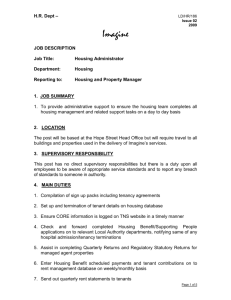

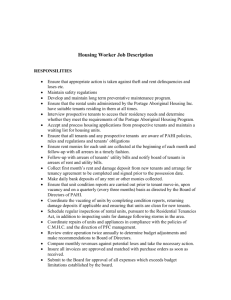

advertisement