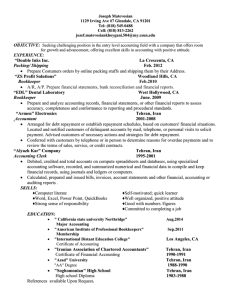

AND B.A., Tehran University M.A., Tehran University

advertisement