Does Design Make a Difference: An Analysis ... Under Which Youth Centers Operate Sarah Shin by

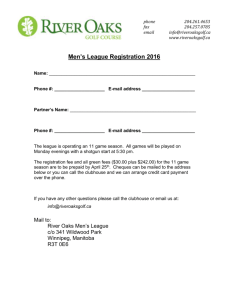

advertisement