2014 From Research to Action Ball State university 1

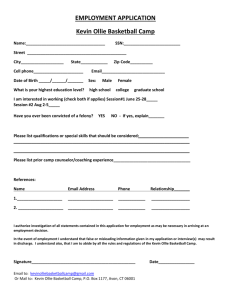

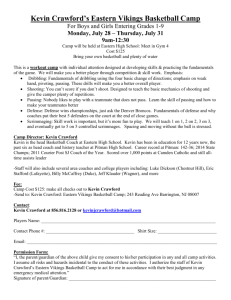

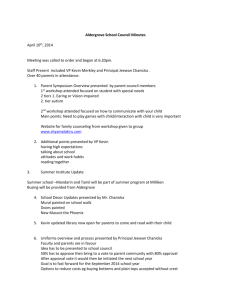

advertisement