UNIT 1 LINEAR PROGRAMMING Structure

advertisement

Linear Programming

UNIT 1

LINEAR PROGRAMMING

Structure

NOTES

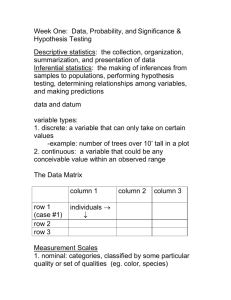

1.0 Introduction

1.1 Unit Objectives

1.2 Basic Structure of LP Problem

1.3 Properties of the LP Model

1.4 Application Areas of Linear Programming

1.5 General Mathematical Model of LPP

1.6 Formulation of LP Model

1.7 Examples on LP Model Formulation

1.8 Solution of LPP

1.8.1 Graphical LP Solution

1.9 Some Special Cases in LP Solution

1.10 Solution of LPP Using Simplex Method

1.11 Special Cases in Simplex Method

1.12 Sensitivity Analysis

1.13 Summary

1.14 Key Terms

1.15 Question & Exercises

1.16 Further Reading and References

1.0 Introduction

Linear programming (LP) can best be defined as a group of mathematical

techniques that can obtain the very best solution to problems which have many possible

solutions. Linear programming can be used to solve a variety of industrial problems. In

most of the situations, resources available to the decision maker are limited. Several

competing activities require these limited resources. With the help of linear

programming those scarce resources are allocated in an optimal manner on the basis of

a given criterion of optimality. In most of the situations, the criterion of

optimality is either maximization of profit, revenue or minimization of cost, time and

distance, etc.

1.1 Unit Objectives

After studying this unit, you should be able to

Understand Basic Structure of LP Problem

Know the properties of LP Model

Know the Application areas of Linear Progrmming

Quantitative Techniques in

Management : 1

Linear Programming

NOTES

Understand formulation of LP Model

Understand Graphical and Algebraic (Simplex) Methods of solution of LP

Models

Use of slack, surplus and artificial variables in LP solution

Use of Big-M and Two phase methods to handle artificial variables

Understand solution process to handle changes in constraints and changes in

objective function with sensitivity analysis.

1.2 Basic Structure of LP Problem

Structure of all LPP has three important components.

(1) Decision variables (activities) : These are activities for which we want to

determine a solution. These are usually denoted by x1, x2, ...., xn.

(2) The objective function (goal) : This is a function which is expressed in terms

of decision variables and we want to optimize (maximize or minimize) this function.

(3) The constraints : These are limiting conditions on the use of resources. The

solution of LPP must satisfy all these constraints.

1.3 Properties of the LP Model

In linear programming, the word linear refers to linear relationship among variables

in a model. The word “programming” refers to modelling and solving a situation

mathematically. In a LP model, the objective and the constraints are all linear function

and are expressed in terms of decision variables. Any LP model must satisfy following

basic properties :(1) Proportionality (Linearity) : The contribution of each activity (decision

variable) in both the objective function and the constraints to be directly

proportional to the value of the variable.

(2) Additivity : In LP models, the total contribution of all the activities in the

objective function and in the constraints to be the direct sum of the individual

contributions of each variable.

(3) Certainty : In all LP models, all model parameters such as availability of

resources, profit (or cost) contribution of a unit of decision variable and use

of resources by a unit of decision variable must be known and constant.

1.4 Application Areas of Linear Programming

LP is one of the most popular technique to find best solution in variety of situations.

Some of the common applications of LP are :-

Quantitative Techniques in

Management : 2

(1) Agricultural Applications : LP can be applied in agricultural planning. e.g.

allocation of limited resources such as acreage, labour, water supply and

working capital, etc. in such a way so as to maximize net revenue.

(2) Military Applications : LP can be applied to maximize the effect of military

operations as well as to minimize the travel distance and cost of operations.

(3) Production Management : Most of the examples of LPP are related to

develop a suitable product mix. A Company can produce several different

products, each of which requires the use of limited production resources.

Product mix is developed using LP, knowing marginal contribution and amount

of available resource used by different product. The objective is to maximize

the total contribution, subject to all constraints.

Linear Programming

NOTES

Similarly LP can be used in production planning to minimize total operation

costs, in assembly line balancing to minimize the total elapse time, in blending

problem to determine minimum cost blend and also to minimize the trim losses

in case of products of standard size.

(4) Financial Management : LP is used for deciding investment activity among

several other activities in such away which maximizes the total expected

return or minimize risk under certain conditions.

(5) Marketing Management : LP may be used in determing the media mix to

maximize the effective exposure within constraints of budget and circulation

/ reach of various media. LP can be used for determining location of

warehouses and other facilities to minimize cost of distribution of products.

(vi) Personnel Management :- LP is used to allocate available manpowers to

different shifts / duties to minimize overtime cost or total manpower.

LP has also find applications in capital budgeting, health care, diet- mix, cupala

charging, fleet utilization and many more such situations.

1.5 General Mathematical Model of LPP

Let us consider n decision variables x1, x2.... xn.

Contribution of each of these decision variable is c1, c2.... cn respectively. So as to

Optimize (Max. or Min.) Z = c1 x1+c2x2 + ......... + cnxn.

Let us consider m constraints.

Total Available

of resource 1

Constraints are expressed as follows :-

a11 x1 + a12 x2 + .... + a1n xn (< or = or >) b1

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

a21 x1 + a22x2 + ....+a2nxn (< or = or >) b2

○

This coefficient

represent amount of

resource 2 used by per

unit of activity 1, i.e. x1)

am1 x1+ am2 x2+ .... +amn xn (< or = or >) bm

Unless specified, in all LP models nonnegativity constraints are also included.

These constraints signify that decision variables can take only non negative values.

These are expressed as x1 > 0, x2 > 0 ..... xn > 0

The above formation can also be expressed in a compact form using summation

sign.

Quantitative Techniques in

Management : 3

Linear Programming

n

Optimize (Max. or Min.) Z = Σ cj xj

(objective function)

j=1

NOTES

Subject to constraints

n

Σ aijxj (< or = or >) bi ; i=1, 2 .... m (constraints)

j=1

and xj > 0 ; j=1, 2...n

(Non negativity Constraints)

In all LP situation, left hand side of constraints is either less than, or equal to or

greater than right hand side. In a particular case of a resource, only one possibility may

take place.

1.6 Formulation of LP Models

Usefulness of LP technique starts with modlling of a given situation in a standard

form as shown in section 1.5. Various steps involved in modelling of LPP are as follows.

(i)

Indentify the decision variables and express them in terms of algebraic

symbols. (Mostly x1, x2... xn).

(ii) Indentify contribution of each of these decision variable in objective which is

to be optimized (maximize or minimize). Express objective function as shown

in section 1.5.

(iii) Identify different resources or conditions which are to be satifsied. Develop

constraint inequality for each constraint. Be careful for the sign (less than,

equal to, greater than) in writing constraints.

Also add non negativity constraints for all decision variables.

1.7 Examples on LP Model Formulation

Example 1 : A manufacturer wishes to determine how to make products A and B

so as to realize the maximum total profit from the sale of the products. Both products

are made in two processes I and II. It takes 7 hours in process I and 4 hours in process

II to manufacture 100 units of product A. It requires 6 hours in process I and 2 hours in

process II to manufacture 100 units of product B. Process I can handle 84 hours of

work and process II can handle 32 hours of work in the scheduled period. If the profit

is Rs. 11 per 100 units for product A and Rs. 4 per 100 units for product B, then how

much of each of products A and B should be manufactured to realize the maximum

profit? It is assumed that whatever is produced can be sold and that the set-up time on

the two processes is negligible. Formulate the above problem as a linear programming

model.

Solution :

Step 1 : Let

Quantitative Techniques in

Management : 4

x1 = number of Product A (in 100's)

x2 = number of Product B (in 100's)

}

There are decision variables.

Step 2 : Now contribution of per 100 units of product A is Rs 11 and contribution of per

100 units of product B is Rs. 4

Linear Programming

Therefore total contribution is 11x1 + 4x2

We want to maximize this total contribution function, which is objective of this

model. Therefore, objective function becomes,

NOTES

Maximize Z = 11x1 + 4x2

Step 3 : Identification of resources : Here two resources are given, namely, process I

and process II.

For process I, total use should be less than or equal to maximum capacity to

handle, i. e. 84 hrs.

So Constraint for process I is 7x1+ 6x2 < 84

Similarly, for process II, 4x1 + 2x1 < 32

Also nonnegativity constraints will be x1, x2 > 0

Example 2 :

A company manufactures three grades of a product A, B and C. The plant operates

on a three shift basis and the following data are available from the production records.

Requirement of Resources

Grade

Availablility

A

B

C

(Capacity per month)

0.25

0.12

0.80

500 tonnes

Mixing (Kilolitres per machine shift) 2.0

3.0

5.0

100 machine shifts

Packing (Kilolitres per shift)

10.0

10.0

80 shifts

Special additive (kgs per litre)

10.0

There are no limitations on other resources. The particulars of sales forecasts and

estimated contribution to overheads and profits are given below.

A

B

C

Maximum possible sales per month (kilolitres)

100

400

600

Contribution (Rs. per kilolitre)

4000

3500

2000

Due to Commitments already made, a minimum of 150 kilolitres per month of `C`

has to be necessarily supplied during the next year.

Just as the company was able to finalise the monthly production programme for

the next 12 months, an offer was received from a nearby competitor for hiring 25

machine shifts per month of mixing capacity for grinding `B` product, that can be spared

for at least a year. However, profit margin of `B` product will reduce by Rs. 1 per litre,

for the amount of product produced on hired facility. Formulate the LP model for

determining the monthly production programme to maximize contribution.

Quantitative Techniques in

Management : 5

Linear Programming

Solution :

Step 1 : Identification of decision variables :

x1 = Monthly quantity of product A (kilolitres)

Let

NOTES

x2 = Monthly quantity of product B using conpany's facilities (Kilolitres)

x3 = Monthly quantity of product B using hired facilities (Kilolitres)

x4 = Monthly quantity of product C (Kilolitres)

Step 2 : Development of objective function :

Contribution per kilolitre

Decision Variable Total contribution

4000

x1

4000x1

3500

x2

3500x2

Working or Hired facility 3500 - 1x 1000 = 2500 x3

2500x3

2000

x4

2000x4

So complete objective function is

Maximize Z = 4000x1 + 3500x2 + 2500x3 + 2000x4

Step 3 : Development of constraints ;

(i)

Special additive constraint :

0.25x1 + 0.12x2 + 0.12x3 + 0.80x4 < 500 (tonnes)

(ii)

Own mixing facility constraint

x1

+

2.0

(iii)

x2

+

3.0

x4

< 100 (machine shifts)

5.0

Hired mixing facility constraint

x3

< 25 (machine shifts)

3.0

(iv)

Packing Constraint

x1

+

10.0

(v)

x2

10.0

x3

10.0

+

x4

10.0

Marketing constraint

< 100

For product A

x1

For product B

x2+x3 < 400

For product C

150

Step 4 : Non negativity constraints

x1, x2, x3, x4 > 0

Quantitative Techniques in

Management : 6

+

< x4 .... 600

< 80 (shifts)

Linear Programming

Example 3 : ABC limited has a flect of 4 different type of 120 coaches, which operates

along 4 routes. Details of capacity, daily trips of each coach and the number of customers

expected for each route during a certain period are as follows :

Type of Capacity

Number of

Coach (passengers) coaches Available

Number of daily trips on route

1

2

3

4

1

50

30

4

5

6

4

2

60

50

2

4

3

3

3

30

20

1

2

1

2

4

40

20

2

3

2

3

250

300

200

400

Daily Number of Customers

NOTES

x1

The operational cost / trip and penalty cost if a customer is not given service is

given below :

Type of Coach

Operation cost / Trip on given route (Rupees)

1

2

3

4

1

250

700

200

500

2

400

500

500

300

3

600

350

400

600

4

350

400

450

250

Penalty cost per customer

50

40

30

60

Formulate the above situation as a LPP

Solution :

Let xij denote the number of trips made by ith type of coach along route J.

i varies from 1 to 4 and j also varies from 1 to 4.

Note : It is assumed that during each trip, coach carry passengers to its full capacity.

Developing objective function

It is required to operate trips of each coach in order to minimize operational cost/

trip, penalty cost to maximize profit, i. e.

Minimize Z

=

250x11 + 700x12 + 200x13 + 500x14

+ 400x21 + 500x22 + 500x23 + 300x24

+ 600x31 + 350x32 + 400 x33 + 600 x34

}

Operational Cost

Component

+ 350 x41 + 400 x42 + 450 x43 + 250 x44

+ 50 (250-50x11-60x21-30x31-40x41)

+ 40 (300-50x12-60x22-30x32-40x42)

+30(200-50x13-60x23-30x33-40x43)

+60 (400-50x14-60x24-30x34-40x44)

}

Penalty cost

Component

Sample Calculation of penalty cost is as follows :

Penalty Cost on route 1 is

50x Number of Customers not given service on route1.

Quantitative Techniques in

Management : 7

Linear Programming

50x [ Daily number of customers on route1 -

50 x Number of trips made by first

type of coach on route 1

60 x Number of trips made by

second type of coach on route 1

NOTES

30 x Number of trips made by

third type of coach on route 1

40 x Number of trips made by

fourth type of coach on route 1

Threrore penalty cost on route is

50 [250 - 50x11 - 60x21 - 30x31 - 40x41]

Similarly penalty coast on route 2,3 and 4 is calculated

Developing Constraints :

(i)

Capacity Constraints :

The number of passengers carried along any route is the sum of passengers

carried by each type of coach is the total number of trips made, viz.

50x11 + 60x21 + 30x31 + 40 x41 < 250

50x12 + 60x22 + 30x32 + 40 x42 < 300

50x13 + 60x23 + 30x33 + 40 x43 < 200

50x14 + 60x24 + 30x34 + 40 x44 < 400

(ii) Maximum number of trips constraints

Total number of trips constraints.

Total number of trips made by a given type of coach along a route cannto exceed

the product of number of coaches available and number of daily trips on that route. It

will be expressed as follows :

X11< 30 x 4

X21 .. 50 x 2

X31 .. 20 x 1

X41 .. 20 x 2

X12< 30 x 5

X22 .. 50 x 4

X32 .. 20 x 2

X42 .. 20 x 3

X13< 30 x 6

X23 .. 50 x 3

X33 .. 20 x 1

X43 .. 20 x 2

X14< 30 x 4

X24 .. 50 x 3

X34 .. 20 x 2

X44 .. 20 x 3

Finally add non negativity constraints :

Xij > 0, for all i and j.

1.8 Solution of LPP

Once a LP model is ready, next step is to find solution of this model. Solution of LP

model can be done either graphically or using simplex methos.

1.8.1 Graphical LP Solution

Quantitative Techniques in

Management : 8

A LPP can easily be solved by graphical method when it involves two decision

variables.

Linear Programming

The process includes two steps :

1

Determination of the feasible solution space.

Any solution (values of decision variables) which satisfy the constraints and non

negativity restrictions of LP model is known as feasible solution.

NOTES

Within the feasible solution space, feasible solution correspond to the extreme (or

corner) points of the feasible solution space.

2

Determination of the optimum solution from among all the feasible points in the

solution space.

Any basic feasible solution which optimizes (maximize or minimize) the objective

function of a LP model is called an optimum solution.

The optimal feasible solution, if it exists, will occur at one, or more, of the extreme

points that are basic feasible solutions.

The procedure uses two examples to show how maximization and minimization

objective functions are handled.

Example 4 :

Solve graphically following LP model :

Maximize Z = 5x1 + 4x2

Subject to constraints :

6x1 + 4x2 < 24

(1)

x1 + 2x2 < 6

(2)

-x1 + x2 < 1

(3)

x2 < 2

(4)

x1, x2 > 0

(5) & (6)

Solution :

Step 1 : Consider a graphical plane. First, we account for the non negativity

constraints which are given in inequality (5) & (6) i. e. x1> 0 and x2 > 0. In figure no. 1,

the horizontal axis and the vertical axis represent the x1 and x2 variables respectively.

xx2

2

x1

x1

Fig. 1

Thus, the nonnegativity of the variables restricts the solution space area to the

first gradrant that lies above the x1 - axis and to the right of the x2 - axis.

Step 2 : Each of the four constraints expressed as inequalities will be treated as

Quantitative Techniques in

Management : 9

Linear Programming

equalities and, then their respective intercepts on both the axis can be determined.

(i)

NOTES

For first constraint, after replacing 6x1 + 4x2 < 24 with the straight line 6x1+ 4x2 =

24, we can determine two distinct points by first setting x1 = 0 to obtain x2 = 6 and

then setting x2 = 0 to obtain x1 = 4. Thus we get a line passed through the two

points (0, 6) and (4, 0) as shown by line (1) in fig. 2.

x2

5

5

(0, 6) 6

5

(1)

4

3

2

1

(4, 0)

0

1

2

3

4

6

5

x1

x1

6

Fig. 2

Next, consider the effect of inequality. The line 1 divides the (x1, x2) plane. into

two half- spaces, one on each side of the graphed line. Only one of these two halves

satisfies the inequality. To determine the correct side, choose (0, 0) as a reference

point. If it satisfies the inequality, then the side in which it lies is the feasible half-space,

otherwise the other side is. To illustrate the use of the reference point (0, 0), in this

inequality (6 x 0 + 4 x 0 = 0) it is less than 24, the half - space represnting the inequality

includes the origin. This is shown by direction of arrow for (1) in figure 2. It is convenient

computationally to select (0, 0) as the reference point, unless the line happens to pass

through the origin in which case any other point can be used

(ii) Similarly for constraint 2, x1 + 2x2 < 6, we get points (6, 0) and (0, 3). Using

reference point method, this inequality includes the origin, Figure 3 shows common

area which satisfies inequality 1, 2 and non negativity constraints.

x2

5

8

7

6

5

4

1

3

2

2

1

0

6

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

x1

Fig. 3

Quantitative Techniques in

Management : 10

(iii) Finally, figure 4 shows the feasible solution space of the given LPP. The feasible

solution space satisfies all six constraints simultaneously. Any point in or on the

boundary of the area ABCDEF is part of the feasible solution space. All points

outside this area are infeasible, as these points do not satisfy one or more than one

constraints.

Linear Programming

NOTES

Fig. 4

Step 3 : Since the value of x1 and x2 have to lie in the shaded area which contains

an infinite number of points would satisfy the constraints of the given LPP. But we are

confined only to those points which correspond to corners of solution space. Thus, as

shown in figure 4, the corner points of feasible region are A = (0, 0), B = (4, 0), C = (3,

1.5), D = (2, 2), E = (1, 2), F = (0, 1).

Step 4 : Value of objective junction at corner points

Corner

points

Coordinates

of corner points (x1, x2)

Objective Function

Z = 5x1 +4x2

Value

A

(0, 0)

5 (0) + 4 (0)

0

B

(4, 0)

5 (4) + 4 (0)

20

C

(3, 1.5)

5 (3) + 4 (1.5)

21

D

(2, 2)

5 (2) + 4 (2)

18

E

(1, 2)

5 (1) + 4 (2)

13

F

(0, 1)

5 (0) + 4 (1)

4

Here we see that maximum value of objective function is 21 which is obtained at

the point C = (3, 1.5), i. e. x1 = 3 and x2 = 1.5 are values of decision variables.

Example 5

: Minimize Z

= .3x1 + .9x2

Subject to

x1 + x2 > 800

.21x1 - .30x2 < 0

.03x1 - .01x2 > 0

x1, x2 > 0

Solution :

Figure 5 provides the graphical solution of the model.

Quantitative Techniques in

Management : 11

1500

Mi

nim

ize

0

Z=

.3x

1

2

1000

+.

9x

2

A

<0

.3x 2

1x1

.2

500

B

=

+x 2

x1

(Students are advised to select

a point on any side of a particular

constraint, and if that point satisfies

constraint then direction of constraint

is towards it otherwise it will be

directed opposite to that point.

Verify.)

x2

01x

>

It is also to be noted that (0, 0)

cannot be used as a reference point

to know the direction of constraint 2

and 3.

1

NOTES

Check that second and third constraints pass through origin. To plot these constraints

as straight lines, we need one additional point. (Student should take any value of x1,

such as 100 or 200 in constraint 2 and compute x2 Similarly assume one value of x1 for

constraint 3 and compute corresponding value of x2)

03x

-

Linear Programming

0

80

Another important point to

0

500

1000

1500 6 x

1

understand is about closed feasible

Fig. 5

solution space. Here objective

function is of minimization nature so we can get a solution otherwise it will become a

case of unbounded solution. (Unbounded solution will be discussed later in the chapter.)

Next we will calculate value of objective function at two corner points, A and B.

At point A, x 1 = 200,

x2 = 600 and

At point B, x 1 = 470.6,

x2 = 329.4 and Z = 437.64

Z = 600

So the minimum value of Z lies at B giving solution as x1 = 470.6 and x2 = 329.40.

1.9 Some Special Cases in LP Solution

(1) Multiple optimal solution or Alternative optima : In two earlier examples,

optimal value of objective function lies at one of the corner points of the feasible

solution space. But it is also possible in some situations, when optinal solution

obtained is not unique. It happens when objective function (line equation of objective

function) is parallel to one of the lines showing constraint in making the feasible

space. In this case infinite number of solutions will take place giving same value of

objective function but with different combinations of decision variables.

Students should verify case of multiple optimal solution with objective function

Z = 2x1 + 4x2 in example 4.

This objective function is parallel to constraint (2), represented by line segment

CD in feasible solution space. All points on this segment give Z = 12.

Quantitative Techniques in

Management : 12

(2) Unbounded Solution : In some LP models, the values of one or more decision

variables can be increased indefinitely without violating any constraint.

Correspondingly value of objective function is also increased indefinitely. Students

should verify for a LP model having objective function of maximize Z = 2x1 + x2,

Subjected to constraints of x1 - x2 < 10 and 2x1 < 40 with non negativity conditions.

They will find that the solution space is unbounded in the direction of x2, and the

value of Z can be increased indefinitely. Unboundedness normally occurs because

of poor construction of model.

Linear Programming

NOTES

(3) Infeasible Solution : In some cases, constraints are incosistent. Then, no common

feasible area can be obtained. This situation can only occur when some constraints

are of the type < and some are of the type >.

When no common feasible area is available, it means that solution is not possible

for this model.

Students should verify for a LP model having objective function of maximize Z

= 40x1+60x2 Subject to constraints of 2x1 + x2 > 70, x1 + x2 < 40 and x1 + 3x2 > 90

with non negativity conditions.

From the practical point, an infeasible solution space points to the possibility

that the model is not formulated correctly.

1.10 Solution of LPP Using Simplex Method

Graphical solution method discussed earlier is suitable for two decision variables.

Solution always occur at one of the corner points of feasible solution space. Values of

decision variables (x1, x2) can be determined for different corner points by solving

linear equations of constraints giving birth to a corner point. We test value of objective

function for different pairs of values of decision variable to decide optimum values of

decision variables. But in real world many decision variables are possible in LP models.

In case of more than two decision variables, simplex method is more useful. The simplex

method enumerates solution only at few selected corner points, if we compare with

graphical method.

To start simplex process of solving LPP, first we should be careful for following

two conditions :(i)

All the constraints (except non negativity constraints for decision variables)

are equations with non negative right hand side.

(ii) All the variables are non negative.

[Note : All computer programmes directly accept inequalities. Just we need to

keep positive RHS.]

How to convert inequalities into equations

Consider an inequality, 2x1 + 3x2 < 12

To convert this type of inequality into equation, we add a variable in LHS of this

inequality as follows.

2x1 + 3x2 + S = 12, with S > 0

This `S` is unused or slack amount of this resource. `S` here is known as slack

variable.

Now consider another inequality, 3x1 + x2 > 8.

Quantitative Techniques in

Management : 13

Linear Programming

Here we subtract a variable in LHS of the inequality.

3x1 + x2 - S = 8, with S > 0

NOTES

This `S` is amount by which LHS exceeds the minimum limit. It represents a

surplus. `S` here is known as surplus variable.

In case of negative RHS such as 2x1 - 3x2 < - 2

We can do 2x1 - 3x2 + S = -2 and then -2x1 + 3x2 - S = 2

Or we multiply both sides of inquality by -1. This will also change sign of inequality

from

(<) to (>)

So whenever (<) sign is there a slack variable is added and in case of (>)

a surplus variable is subtracted to convert inequalities into equations.

Important definitions for simplex method

In a simplex model where m equations and n variables (m < n) are there, only m

variables are part of solution. These m variables are known as basic variables.

Remaining n - m variables are non- basic variables. Solution obtained from basic

variables is known as basic solution of the model. In case all variables in basic solution

are non negative, it is a basic feasible solution.

One of the basic feasible solution will give best value of the objective function.

This best value (maximum in a maximization problem and minimum in a minimization

problem) is the optimum solution of given LPP.

Computation using Simplex Method

To explain the process of solving a LPP using simplex method, we will consider an

example of maximization type. Necessary steps will be discussed with the help of this

example.

Example 6 : Maximize Z = 5x1 + 4x2

Subject to

6x1 + 4x2 < 24

x1 + 2x2 < 6

-x1 + x2 < 1

x2 < 2

x1, x2 > 0

Solution

Step 1 : Convert constraint inequalities into equations :

6x1 + 4x2 + S1

= 24

1st constraint

x1 + 2x2

=6

2nd constraint

=1

3rd constraint

=2

4th constraint

-x1 + x2

Quantitative Techniques in

Management : 14

x2

+ S2

+ S3

+ S4

Linear Programming

x1, x2, s1, s2, s3, s4 > 0

Here variables S1, S2, S3 and S4 are the slacks associated with the respective

constraints.

We will also add these slack variables in objective function but with `0` (zero)

coefficients. So objective function will be

NOTES

Max Z = 5x1 + 4x2 + 0s1 + 0s2 +0s3 +0s4

For further computation, we write the objective equation as

Z - 5x1 - 4x2 = 0

Step 2 : Starting Simplex table :

With the help of objective equation and constraint equations, we will make initial

simplex table. The design of the table specifies the set of basic and non basic variables

as well as provides the solution associated with the starting iteration.

Standard desing of the simplex table used in iteration process is as follows :

Basic

Variables

Z

Decision, slack / surplus variables

Z ROW

1

Co efficient of various variables in

objective equation

0

0

0

Coefficients of different variables

↓

↓

Solution

RHS

according to row.

Fig. 6

To make starting simplex table, we need initial basic variables. In this model four

constraints are given and total variables are six (two decision variables x1 and x2 and

four slack variables S1, S2, S3 and S4). So only four variables will be basic variables and

two will be non basic variables.

Normally decision variables are given zero values and slack variables are initial

basic variables. In this example

Nonbasic (zero) variables

: (x1, x2)

Basic variables

: (s1, s2, s3, s4)

With this initial consideration

Z=0

S1 = 24, S2 = 6, S3 = 1, and S4 = 2

Now we will put this initial information in standard simplex table design as shown

in figure 6.

Quantitative Techniques in

Management : 15

Linear Programming

Table I : Initial Table

NOTES

Basic

Z

X1

X2

S1

S2

S3

S4

Solution

Z

1

-5

-4

0

0

0

0

0

S1

0

6

4

1

0

0

0

24

S2

0

1

2

0

1

0

0

6

S3

0

-1

1

0

0

1

0

1

S4

0

0

1

0

0

0

1

2

Step 3 : To check for optimality

After preparing simplex table, we need to check optimality of this solution. In this

case objective function Z = 5x1 + 4x2 shows that the solution can be improved by

increasing x1 or x2. In simplex table we write objective function as Z - 5x1 - 4x2 = 0. If

any variable with negative coefficient in Z row is available, it means value of Z can be

improved and it is known as optimality condition. Optimality condition will be satisfied if

all variables in 2 row has non negative coefficients. So any variable with higher negative

coefficient will improve the value of Z faster.

This rule is referred to as the optimality condition. It means that currently nonbasic

variable x1 will enter into the solution. This is known as entering variable. If two or

more non basic variables in Z row are having same maximum negative coefficient, it

means a tie for entering variable. Tie is broken arbitrarily.

When a new variable will enter into the solution one of the existing basic variable

will become nonbasic variable. This is known as leaving variable.

To determine leaving variable : We compute the nonnegative ratios of right hand

side of the equations (Solution Column) to the corresponding constraint coefficients

under the entering variable, x1, as the following table shows :

Basic

s1

Entering

x1

Solution

Ratio

6

24

24

= 4 (Minimum Ratio)

6

s2

1

6

6

=6

1

s3

-1

1

1

= ignored

-1

s4

0

2

2

= ignored

0

Quantitative Techniques in

Management : 16

Decision : To enter x1 in the solution, s1 will be the leaving variable.

The minimum non negative, ratio identifies the current basic variable as leaving

variable. Value of x1 after becoming basic variable will be 4. As in case of entering

variable, two or more basic variable can have similar valid minimum ratio. It is a tie for

leaving variable. This tie can also be broken arbitrarily.

Linear Programming

NOTES

Now we will prepare table II in the solution process by swapping the entering

variable x1 and the leaving variable s1 in the simplex table to produce the following sets

of nonbasic and basic variables :

Nonbasic (zero) variables :

(s1, x2)

Basic variables

(x1, s2, s3, s4)

:

The swapping process is based on the Gauss - Jordan row operations. Process of

Gauss - Jordan row operations is as follows :

1.

Pivot Column : This is the column of entering variable.

2.

Pivot Row : This is the row of leaving variable.

3.

Pivot Element : The element in table obtainted as a result of intersection of

pivot row and column.

Let us reproduce our original table below :

Entering variable (x1 is most negative in z row)

Leaving variable (min. non

negative ratio of solution

and corresponding pivot

column element)

↓

↓

Basic

Z

x1

x2

s1

s2

s3

s4

Solution

Z

1

-5

-4

0

0

0

0

0

S1

0

6

4

1

0

0

0

24

S2

0

1

2

0

1

0

0

6

S3

0

-1

1

0

0

1

0

1

S4

0

0

1

0

0

0

1

2

Pivot row

Pivot column

Pivot element

To get new table from current table, Gauss - Jordan operation will be done in two

steps. First to get new row elements of pivot row and then get elements for all other

rows in table.

(1) To get new pivot row, we will divide all elements of existing pivot row by pivot

element. Thus new pivot row in this case will be

Z

x1

0

6

=0

X1

6

x2

4

=1

6

6

s1

2

=/

3

s2

1

s3

s4

0

0

=0

6

6

RHS

0

=0

=0

6

24

6

=4

6

Quantitative Techniques in

Management : 17

Linear Programming

(2) To get all other rows including z row, we will perform following calculation :

New row = (Current row) - (Its pivot column coefficient) x (New pivot row)

e. g. to get new z row

NOTES

New z row = (current z row) - (-5) (New x1 row)

= (1 -5

-4

0 0 0 0 0)

-

(-5)

(0

2

3

= (1 0 -

1

2

1

3

6

0 0 0 4)

5

0 0 0 20)

6

Students are advised to do calculations for other rows of table.

The new basic solution has rows for z, x1, s2, s3 and s4.

The table will be as follows

Entering variable

↓

z

x1

x2

s1

s2

s3

s4

Solution

z

1

0

- 2/ 3

5

/6

0

0

0

20

Ratio

x1

0

1

2

/3

1

/6

0

0

0

4

s2

0

0

4

/3

- 1/ 6

1

0

0

2

6 Pivot

Column

3

/2

s3

0

0

5

/3

1

0

1

0

5

3

s4

0

0

1

0

0

1

2

2

↓

↓

Leaving variable

/6

0

↓

Basic

Pivot Column

Using the concept of optimality we find here that one of the variable in z row is

with negative coefficient. It implies that solution is not optinal and x2 will be our new

entering variable. To find leaving variable we will perform as usual following calculation.

Entering variable

Colum (x2)

RHS

(Solution Column)

Ratio

x1

2

/3

4

4

s2

4

/3

2

s3

5

/3

5

s4

1

Basic

2/

2

=6

/

3

=1.5 (minimum)

/

4/

3

2

5

5/

2

=3

/

/

1

3

=2

Leaving variable

Here minimum ratio is corresponding to S2 variable. So S2 is new leaving variable

making space for entering variable x2.

New rows for table will be computed as follows.

New pivot (x2) row

Quantitative Techniques in

Management : 18

Linear Programming

1

(current s2 row)

=

4/3

3

(0

=

0

4/3

-1/6

1

0

0

2)

NOTES

4

New z row

= current z row - (-2/3) (new x2 row)

Similarly new x1, s3 and s4 rows will be computed. Resulted table will be as

follows:

Basic

z

x1

x2

s1

s2

s3

s4

Solution

z

1

0

0

3

/4

1

/2

0

0

21

x1

0

1

0

1

/4

- 1 /2

0

0

3

x2

0

0

1

- 1 /8

3

/4

0

0

3

/2

s3

0

0

0

3

/8

- 5 /4

1

0

5

/2

s4

0

0

0

1

/8

- 3 /4

0

1

1

/2

Again using the condition of optimality, we see that all coefficients in z row are

non negative. Hence current table is optimal.

We read optimal solution as follows :

Z = 21 with x1=3 and x2 = 3/2

Since S3 = 5/2 and s4 =1/2 are also present in the final table, we conclude that

resource 3 and resource 4 are available in abundant. As S1 and S2 are not part of final

solution, we conclude that first two resourices are scarce.

Example 7 : Maximize Z - 2x1 +x2 - 3x3 + 5x4

Subject to

x1 + 2x2 + 2x3 + 4x4 < 40

2x1 - x2 + x3 + 2x4 < 8

4x1 - 2x2 + x3 - x4 < 10

x1, x2, x3, x4 > 0

Solution : Convert constraints into equations :

x1 + 2x2 + 2x3 + 4x4 + s1

= 40

2x1 - x2 + x3 + 2x4

=8

4x1 - 2x2 + x3 - x4

+ s2

+ s3

= 10

x1, x2, x3, x4, s1, s2, s3 > 0

Initial basic solution can be obtained by putting x1, x2, x3, x4 = 0

so initial basic feasible solution is

(s1, s2, s3) = (40, 8, 10)

Quantitative Techniques in

Management : 19

Linear Programming

Simplex tables will be as follows : ↓

NOTES

↓

Basic z

x1

x2

x3

x4

s1

s2

s3

Solution

z

1

-2

-1

3

-5

0

0

0

0

Ratio

s1

0

1

2

2

4

1

0

0

40

10

s2

0

2

-1

1

2

0

1

0

8

4

s3

0

4

-2

1

-1

0

0

1

10

-10 (ignored)

Second table will have s1, x4, s3 as basic variables

↓

↓

Basic z

x1

x2

x3

x4

s1

s2

s3

solution

z

1

3

- 7 /2

11

0

0

5

/2

0

20

Ratio

s1

0

-3

4

0

0

1

-2

0

24

6

x4

0

1

- 1 /2

1

/2

1

0

1

/2

0

4

-8 (ignored)

s3

0

5

- 5 /2

3

/2

0

0

1

/2

1

14

-28/5 (ignored)

/2

Third table will have x2, x4 and s3 as basic variables.

Basic z

x1

x2

x3

x4

s1

s2

s3

Solution

z

1

3

/8

0

9

0

7

/8

3

/4

0

41

x2

0

- 3 /4

1

0

0

1

/4

- 1 /2

0

6

x4

0

5

0

1

1

1

/8

1

/4

0

7

s3

0

25

0

4

0

5

/8

- 3 /4

1

29

/8

/8

/2

Check with optimality condition. This last table is optimal one, giving z = 41 with x2

= 6 and x4 = 7. Two of the decision variables, x1 and x3 are non basic in final solution,

i. e. these are with zero values. Since S3 is also in the final table, it means that third

resource is in abundance.

Solution of a LPP using surplus variable :

As shown in Example 6 and 7, LPs in which all constraints are (<) with non

negative RHS can be handled by putting slack variables in constraints to convert these

inequalities into equations. But in case of (>) or (=) constraints, we need to do some

extra efforts to bring these inequalities into standard form of simplex processing.

If (=) constraints are involved, we will use artificial variables only in those

equations. If (>) constraints are involved, we will use surplus and artificial variables in

these inequalities.

Quantitative Techniques in

Management : 20

To handle artificial variables, two popular methods are the M-method and the two

- phase methos.

Purpose of artificial variable is to help in providing initial basic feasible solution of

the problem. Both these methods are developed in such a way that artificial variables

will disappear from final solution.

Note : Students can think that slack and surplus variables may be part of final

solution while artificial variables are not. There is a meaning of slack and surplus variable

while artificial variables have no physical meaning.

Linear Programming

NOTES

M-Method : When we use artificial variables in case of (=) or (>) type constraints,

we put a coefficient M with this variable in the objective function of the problem. M is

considered to be a very large quantity. The purpose of M is to assign heavy penalty for

this artifical variable. So as it does not remain in the solution. If problem is a maximization

one we use -M as artificial variable objective coefficient and if problem is a minimization

one, we use +M as coefficient.

Example 8 : Minimize Z = 3x1 + 8x2

Subject to

x1 + x2 = 200

x1 < 80, x2 > 60; x1, x2 > 0

Solution :

Conversion of inequalities into equations : First constraint will have artificial variable,

R1. Second constraint will have slack variable S1. Third constraint will have surplus

variable S2 and one artificial variable R2.

Since it is a minimization problem R1 and R2 will have +M as objective coefficients

while S1 snd S2 will have "0" objective coefficients.

Problem in standard form will be as follows :

Minimize Z = 3x1 + 8x2 + MR1 + MR2

Subject to

x1 + x2

x1

+ R1

+ s1

= 80

- s2

x2

= 200

+ R2 = 60

x1, x2, s1, s2, R1, R2 > 0

The associated starting basic solution is given by (R1, S1, R2) = (200, 80, 60)

The starting table will be as follows :

Basic

z

x1

x2

S1

S2

R1

R2

Solution

z

1

-3

-8

0

0

-M

-M

0

R1

0

1

1

0

0

1

0

200

S1

0

1

0

1

0

0

0

80

R2

0

0

1

0

-1

0

1

60

Quantitative Techniques in

Management : 21

Linear Programming

Be Careful!

Before we apply condition of optimality for minimization problems here, we need

to make z row consistent with rest of the table.

NOTES

Please check, that current basic solution is (R1, S1, R2) = (200, 80, 60) yielding z =

260M while table shows solution of Z as zero. This incosistency stems from the fact

that R1 and R2 have nonzero coefficients in the z row.

To eliminate this inconsistency, we will perform some row operations. In particular,

see the highlighted elements in the R1 - row and the R2 - row.

Multiplying each of R1-row and R2 - row by M and adding the sum to the current

Z row, we get new Z row.

(-3

-8

0

0

-M

-M

0)

+M

(1

1

0

0

1

0

200)

+M

(0

1

0

-1

0

1

60)

-3+M

-8+2M

0

-M

0

0

260M

Modified table thus becomes

Basic z

x1

Z

1

R1

x2

↓

s1

s2

R1

R2

Solution

(-3+M) (-8+2M) 0

-M

0

0

260M Ratio

0

1

1

0

0

1

0

200

200

S1

0

1

0

10

0

0

0

80

ignored

R2

0

0

1

0

-1

0

1

60

60

This Modified table is a consistent one and fit for applying condition of optimality

and Gauss - Jordon row operations.

Applying optimality condition, we will notice that most positive Z row coefficient

is (-8+2M). Thus x2 is entering variable. (Students are advised to compare (-3+M) and

(-8+2M) for most positivity.)

After comparing the ratios obtained from solution column and pilot column elements,

R2 is chosen as leaving variable.

After applying Gauss - Jordon row operations for new pivot row and for other

rows including Z row, table obtained after iteration is as follows :

↓

Quantitative Techniques in

Management : 22

Basic

z

x1

Z

1

R1

↓

x2

s1

s2

R1

R2

Solution

(-3+M) 0

0

M-8

0

+8-2M 140M + 480

0

1

0

0

1

1

-1

140

S1

0

1

0

1

0

0

0

80

x2

0

0

1

0

-1

0

1

60

New table, after x1 becomes entering variable and s1 is leaving variable, will be as

follows :

Basic

z

x1

x2

s1

s2

R1

R2

Solution

Z

1

0

0

-M+3

M-8

0

8-2M

60M+720

R1

0

0

0

-1

1

1

-1

60

x1

0

1

0

1

0

0

0

80

x2

0

0

1

0

-1

0

1

60

Linear Programming

NOTES

In this table, using condition of optimality S2 will be entering and R1 will be leaving

variable.

New table after iteration will be

Basic

z

x1

x2

s1

s2

R1

R2

Solution

z

1

0

0

-5

0

-8M

-M

1200

s2

0

0

0

-1

1

1

-1

60

x1

0

1

0

1

0

0

0

80

x2

0

0

1

-1

0

1

0

120

This table is optimal Verify!

Optimal solution is Minimum Z = 1200

with x1 = 80 and x2 = 120

Two phase Method :

In two phase method, problem is solved in two phases. Phase I attempts to find a

starting basic feasible solution, and, if one is found, phase II is involed to solve the

original problem.

Example 9 : We will use same problem of example 8 to show various steps of

two- phase method.

Solution :

Phase I

Minimize r = R1 + R2

(A new objective function is defined which is always a minimization irrespective

of nature of original problem. This objective function is sum of artificial variables used

in problem to convert (=) or (>) type constraints into standard form.)

Subject to

x1 + x2

x1

x2

+ R1

+ s1

= 200

= 80

- s2 + R 2

= 60

x1, x2, s1, s2, R1, R2 > 0

Quantitative Techniques in

Management : 23

Linear Programming

NOTES

The associated table is given as with R1, S1, and R2 as initial basic variables.

Basic

x1

x2

s1

s2

R1

R2

Solution

Y

0

0

0

0

-1

-1

0

R1

1

1

0

0

1

0

200

S1

1

0

1

0

0

0

80

R2

0

1

0

-1

0

1

60

To make this table consistent for use of Gauss - Jordan iteration process, as in the

M-Method, R1 and R2 are substituted out in the r-row by using the following row

operation:

New r-row = old r row + (1xR1 row + 1xR2 row)

As a result, modified table is :

Basic

x1

x2

s1

s2

R1

R2

Solution

r

1

2

0

-1

0

0

260

R1

1

1

0

0

1

0

200

S1

1

0

1

0

0

0

80

R2

0

1

0

-1

0

1

60

After two iterations, optimal table will be :

Basic

x1

x2

s1

s2

R1

R2

Solution

r

0

0

0

0

-1

-1

0

s2

0

0

-1

1

1

-1

60

x1

1

0

1

0

0

0

80

x2

0

1

-1

0

1

0

120

Bacause minimum r = 0, phase I produces the basic feasible solution x1 = 80 and

x2 = 120 and s2 = 60

Check that artificial variables (R1 and R2) are not part of this solution. These

variables have done their job of providing a feasible basic solution.

We are now ready for phase II computations.

Phase - II

(i)

Delete columns of artificial variables from optimal table of phase - I.

(ii) Rewrite the problem with original objective function and new constraints

derived from optimal table of phase - I.

Minimize Z = 3x1 + 8x2

Subject to

Quantitative Techniques in

Management : 24

-s1, +s2

= 60

x1 + s 1

= 80

r2 -s1

= 120

Linear Programming

NOTES

x1, x2, s1, s2 > 0

So, associated table with this set of objective function and constraint equations is

Basic

x1

x2

s1

s2

Solution

z

-3

-8

0

0

0

s2

0

0

-1

1

60

x1

1

0

1

0

80

x2

0

1

-1

0

120

In this table also we can see that two basic variables x1 and x2 have non zero

coefficients in z row. These coefficients need to be converted into zeros and associated

row operation required will be

New z row = old z row + (3xX1 row + 8xX2 row)

The initial table of phase II is thus given as

Basic

x1

x2

s1

s2

Solution

z

0

0

-5

0

1200

s2

0

0

-1

1

60

x1

1

0

1

0

80

x2

0

1

-1

0

120

In this table when we apply condition of optimality we realize that it is an optimal

solution. (In a minimization objective function, optimality is achieved when Z row has

no positive coefficient.)

So optimal (minimum) z = 1200 with x1 = 80 and x2 = 120.

1.11 Special Cases in Simplex Method

As mentioned earlier also, similar special cases can be seen during application of

simplex calculations.

(1) Alternative optima or multiple optimal Solution :Consider the following LP formulation :Max. z = 2x1 + 4x2

Subject to

Quantitative Techniques in

Management : 25

Linear Programming

6x1 + 4x2 < 24

x1 + 2x2 < 6

-x1 + x2 < 1

NOTES

x2 < 2

x 1 , x2 > 0

After putting this LPP in tabular arrangement :

Iteration

Basic

x1

x2

s1

s2

s3

s4

Solution

0

z

-2

-4

0

0

0

0

0

s1

6

4

1

0

0

0

24

s2

1

2

0

1

0

0

6

s3

-1

1

0

0

1

0

1

s4

0

1

0

0

0

1

2

z

0

0

0

2

0

0

12

s1

0

0

1

-6

0

8

4

s3

0

0

0

1

1

-3

1

x2

0

1

0

0

0

1

2

x1

1

0

0

1

0

-2

2

5

z

0

0

0

2

0

0

12

Alternative

s4

0

0

0.13

-0.75

0

1

0.50

Optimal

s3

0

0

0.38

-1.25

1

0

2.50

(S4 enters

x2

0

1

-0.13

0.75

0

0

1.50

and S1 Leaves x1

1

0

0.25

-0.50

0

0

3.00

4 (optinal)

Here iteration 4 gives optimal solution with basic variables x1, x2, S1 and s3. In

optimal solution one of the nonbasic variable S4 is having 0 coefficient in z row. This

gives a chance of alternative optima condition. After forcing S4 into the solution, checking

for minimum ratio, S1 becomes leaving variable. Iteration 5 gives another optimal solution

without changing value of solution. In both iterations, 4 and 5, maximum value of Z

remains unchanged, i. e. 12. But in iteration 4, basic variables are x1 = 2, x2 =2, s1 = 4

and s3 = 1, while in iteration 5, basic variables are x1 = 3, x2 = 1.50, s3 = 2.50 and s4 =

0.50

In practical terms, alternative solutions are useful because we can choose from

many solutions without affecting the quality of the objective value.

(2) Unbounded solution :

Consider the following LP formulation

Quantitative Techniques in

Management : 26

Linear Programming

Maximize

Z = 2x1 + 3x2

Subject to

x1 - 2x2 < 15

NOTES

3x1 < 50

x 1 , x2 > 0

Let us make tabular arrangement for this LP.

Iteration

0

Basic

x1

x2

s1

s2

Solution

z

-2

-3

0

0

0

s1

1

-2

1

0

15

s2

3

0

0

1

50

This is a maximization problem and x2 is a candidate to enter into solution space.

But neither s1 nor s2 can leave the solution. This means that x2 can be increased

indefinitely without violating any of the constraints.

Situation of unboundedness is a result of poor model making. It is possible that a

constraint which restricts value of x2 to be increased infinitely is missing.

(3) Infeasible Solution :

Infeasible solution can occur when constraints are having opposite signs of

inequalities.

consider the following problem :

Maximize z = 4x1 + 3x2

Subject to

x1 + 2x2 < 5

2x1 + 3x2 > 10

x1, x2 > 0

Using slack variable S1 in first constraint and S2 surplus variable in second constraint

alongwith artificial variable R1 in second constraint and making this LP model in standard

form.

(We are using a value of 100 for M in the objective function.)

Lteration Basic

x1

x2

s1

s2

R1

RHS

0

Z

-204

-303

0

100

0

-1000

S1

1

2

1

0

0

5

R1

2

3

0

-1

1

10

Z

0

105

204

100

0

20

x1

1

2

-1

-

-

5

R1

0

-1

-2

-1

1

0

2

Quantitative Techniques in

Management : 27

Linear Programming

Second iteration is optimal. But this solution has x1 and artificial variable R1 as

basic variables. Artificial variable, if present in final solution, will give a case of infeasible

solution.

Infeasible solution is a result of poor model construction.

NOTES

(4) Degeneracy :

Sometime it is possible to have a situation of tie for deciding leaving variable.

Minimum ratio is same for two current basic variables. This tie can be broken arbitrasily.

In this case, at least one basic variable will be zero in the next iteration and the new

solution is said to be degenerate.

Consider the following problem.

Maximize z = 2x1 + 5x2

Subject to

x1 + 3x2 < 6

x1 + 2x2 < 4

x1, x2 > 0

Given the slack variables s1, and s2, the following tables provide the simplex

iterations of the problem :

Iteration

Basic

x1

x2

s1

s2

RHS

0

z

-2

-5

0

0

0

x2 enters, s1 or s2

s1

1

3

1

0

6

may leave. Take s1 s 2

1

2

0

1

4

z

- 1/ 3

0

5

/3

0

10

x2

1

/3

1

1

/3

0

2

s2

1

/3

0

- 2/ 3

1

0

as leaving variable.

1

See one of the current basic variable s2 is zero now.

Here x1 will enter and s2 will leave.

2

z

0

0

1

1

10

(Optimum)

x2

0

1

1

-1

2

x1

1

0

-2

3

0

In degeneracy situation, objective value of the function may not improve but

optimality condition remains unsatisfied. It is normally a case of overdetermined problems.

1.12 Sensitivity Analysis

Quantitative Techniques in

Management : 28

Sensitivity analysis tells range of input parameter variation without changing optimal

solution. Following two cases will be discussed to explain the concept of sensitivity

Linear Programming

analysis :

(a) Changes in the RHS of the constraints

(b) Changes in the objective function.

(a) Changes in the RHS of the constraints :

NOTES

Consider the following problem :

Maximize z = 2x1 + x2 + 4x3

Subject to

x1 + 2x2 + x3 < 30

(Resource 1)

3x1 + 3x3 < 60

(Resource 2)

x1 + 4x2 < 20

(Resource 3)

x1, x2, x3 > 0

Here availbility of resources are 30 units, 60 units and 20 units respectively. We

can change availability of these resources within a limit without altering current optimum

solution. We want to determine limits of these changes.

First let us see the optimum table for original model using S1, S2 and S3 as slack

variables in three constraints, respectively.

1.13 Summary

1.14 Key Terms

Feasible Solution : A solution which satisfies all constraints including non-negativity

constraints.

Op[timum Solution : A feasible solution which gives either maximum or minimum

value of objective function.

Quantitative Techniques in

Management : 29

Linear Programming

Slack variable : It represents unused amount of a resource.

Surplus variable : It represents shortage of a resource.

NOTES

Artificial variable : These variables have no physical meaning, except to help in getting

a starting solution.

Basic variables : Decision, slack, surplus or artificial variables which are part of

solution are known as basic variables. In other words, non zero variables are

basic variables.

Non-basic variables : All zero variables are non-basic variables.

Pivot Column : In a simplex table, column of entering variable.

Pivot Row : In a simplex table, row of leaving variable.

1.15 Questions and Exercises

PART - A

Que. 1. A Paint company makes 3 grades of paint (α, β, γ ) from 3 raw materials

(A, B, C). Raw materials are used in making of these 3 grades of paint as follows :

Grade Specifications

Unit selling (Rs.)

price (in per litre)

α

8.0

Not less than 50% raw material `A`

Not less than 25% raw material `B`

β

Not less than 25% raw material `A`

6.5

γ

Not less than 50% raw material `B`

5.5

Within above restrictions, raw materials can be used in any grade of paint. There

are capacity limitations on the amounts of three raw materials that can be used :

Raw material

Capacity

Price / litre

A

500 litres

9.5

B

500 litres

9.5

C

300 litres

6.5

It is required to produce the maximum profit. Formulate a LP model for the problem.

Quantitative Techniques in

Management : 30

Que. 2. A manufacturing company has contracted to deliver home windows over

the next 4 months. The demands for each month are 100, 250, 190 and 110 units

respectively. Production cost per window varies from month to month depending on the

cost of labour, material and utilities. The company estimates the production cost per

window over the next 4 months to be Rs. 500, Rs. 450, Rs. 550 and Rs. 500 respectively.

To take advantage of the fluctuations in manufacturing cost, company may elect to

produce more than is needed in a given month and hold the excess units for delivery in

later months. This however, will incur holding cost at the rate of Rs. 30 per window per

month assessed on end- of - month inventory. Formulate a LP model to determine the

Linear Programming

optimum production schedule.

Que 3. Find solution of following problems using graphical method :

(a) Max

Z=

30x1 + 40x2

NOTES

subject to

x1< 20

x2 > 10

4x1 + 2x2 < 100

4x1 + 6x2 < 180

x1 + x2 < 40

x1, x2 > 0

and

(b) Max. Z = 150 x1 + 250 x2

Subject to

x1

/1500 + x2/4500 > 1

x1 1000 + x2 8000 > 1

/

/

x 2000 + x 4000 > 1

/

/

x 3000 + x 9000 > 1

/

/

and

(c) Min.

1

2

1

2

x1, x2 > 0

20x1 + 40x2

Z=

Subject to

36x1 + 6x2 > 108

3x1 + 12 x2 > 36

20x1 + 10x2 > 100

and

x1, x2 > 0

1.16 Further Reading and References

Quantitative Techniques in

Management : 31

Transportation Model

UNIT 2

NOTES

TRANSPORTATION MODEL

Structure

2.0 Introduction

2.1 Unit Objectives

2.2 Transportation Model

2.3 Steps in Solution Process

2.3.1 Initial Basic Feasible Solution

2.3.2 Method of Multiplier for Optimality Test

2.4 Summary

2.5 Key Terms

2.6 Question & Exercises

2.7 Further Reading and References

2.0 Introduction

Trasportation problems are a special class of linear programming problems.

Transportation problems deal with physical distribution of goods and services from

various supply sources to various demand centres. The structure of a transportation

problem involves a large number of shipping routes from several supply origins to

several demand destinations. The objective is to determine the number of units of an

item which should be shipped from an origin to a destination in order to satisfy the

required quantity of goods or services at each destination centre, within the limited

quantity of items available at each supply centre, at the minimum transportation cost

and/or time.

Transportation models are widely used in supply chain management.

2.1 Unit Objectives

After studying this unit, you should be able to

Quantitative Techniques in

Management : 32

Understand basic structure of transportation model as a special case of linear

programming model.

Understand north-west corner method, least coast method and vogel’s

approximation method to obtain initial basic feasible solution of

transportation model.

Understand process of checking optimality of basic feasible solution using

method of multipliers.

Transportation Model

2.2 Transportation Model

Sources

Destinations

c11 : x11

NOTES

1

b1

2

2

b2

a3

3

3

b3

am

m

n

bn

a1

1

a2

C 11 : X11

Cmn : Xmn

Cmn : Xmn

Fig : 2.1

Fig

: 2.1

Figure 2.1 gives a general type of transportation model. Here we have taken m

supply sources and n demand centres (destinations). Each source can supply to each

destination. If i is a source and j is a particular destination then xij units are shipped

from ith source to jth destination at unit cost of transportation cij. Objective of

transportation model is to ensure fullfillment of demand of each destination such as b1,

b2, .......... bn etc. But no supply centre can supply more than its capacity such as a1, a2

.... am.

Finally, distribution of units from sources to destination is designed in such a way

to incur minimum cost of distribution.

Take following case, before we move to develope transportation model.

Example : A company has two production facilities at Mumbai and Nagpur with

production capacity at 1000 and 800 products per day, respectively. Three warehouses

at the company are at Pune, Gondia and Chandrapur with daily requirements of 900,

400 and 500 products, respectively. Transportation cost (in rupees) per unit between

production facilities to warehouses is given in table 1.

Table 1

Warehouses →

Pune

Gondia

Chandrapur

Mumbai

4

8

7

Nagpur

6

4

3

→

Production facility

With the help of knowledge of liner programming of Unit 1, we can make

following linear programming model :

Consider following decision Variables

X11

→

Units to be transported from Mumbai to Pune

X12

→

Units to be transpoted from Mumbai to Gondia

Quantitative Techniques in

Management : 33

Transportation Model

NOTES

X13

→

Units to be transported from Mumbai to Chandrapur

X21

→

Units to be transported from Nagpur to Pune

X22

→

Units to be transported from Nagpur to Gondia

X23

→

Units to be transported from Nagpur to Chandrapur

Objective function will be

Minimize (total transportation cost) Z

= 4x11 + 8x12 + 7x13 + 6x21 + 4x22 +3x23

Subject to the constraints

(i) Capacity Constraints

x11 + x 12 + x 13 = 1000

x 21 + x 22 + x 23 = 800

(ii) Requirement Contraints

x11 + x 21 = 900

x12 + x 22 = 400

x13 + x 23 = 500

and x11, x12, x13, x21, x22, x23 > 0

The LP model can be solved by the simplex method. However, with the special

structure of the constraints, we can solve the problem more conveniently using the

trasportation table shown the table 2.

Table 2 : Trasportation model for examples 1

Destination →

Pune

Gondia

Chandrapur

Supply

→

Sources

4

8

x12

7

Mumbai

x11

Nagpur

x21

x22

x23

Demand

900

400

500

6

x13

4

1000

3

1000 800

In each cell of table 2, we write units to be transported from one source to a

destination (xij) in lower left side and unit cost of transportation between this pair of

source and destination in upper right hand corner.

Taking table 2 and figure 1 into account, we can develop general mathematical

model of trasportation problem :

m

Min Z =

n

Σ

Σ

i =1

j=1

Subject to the constraints

Quantitative Techniques in

Management : 34

cij xij

n

Σ

Transportation Model

xij = ai i = 1,2 ...... m (supply Constraint)

j =1

m

Σ

NOTES

xij = bj j = 1,2 ...... n (demand Constraint)

i =1

and xij > 0 for all i and j

A necessary and sufficient condition for the existence of a feasible solution to the

trasportation problem is

Total Supply = Total demond

m

n

Σ ai = Σ bj

i=1

j=1

If the problem is unbalanced, we can always add dummy source or a dummy

destination to make the original problem balanced. Transportation Costs in dummy

row or dummy column are always zero.

If in example 1, demand at Pune is 1200 instead of 900 given originally. This will

make total demond of 2100 units daily against a production of 1800 Units daily from

two plants. To solve such unbalanced model, we will add a new dummy source with a

capacity of 300 units. The capacity of new source is total demond - total supply available.

The revised balanced model with dummy source is given in Table 3.

Table 3 : Transportation model with dummy source

Source

Pune

Gondia

4

Chandrapur

8

x12

7

Mumbai

x11

Nagpur

x21

Dummy Source

x31

x32

x33

Demand

1200

400

500

6

x13

4

x22

0

Supply

1000

3

x23

0

800

0

300

Again consider example 1, and see if supply available at both these plants are 100

units daily.

This will produce 2000 units daily againts a total daily demand of 1800 units.

This is also unbalanced problem. We will add a new column (new destination) with a

supply requirement of 200 units. Demand of new destination is total supply- total

demand. The revised balanced model with dummy destination is given in table 4.

Quantitative Techniques in

Management : 35

Transportation Model

NOTES

Table 4 : Transportation model with dummy destination

Source

Pune

Gondia

Mumbai

x11

Nagpur

x21

x22

x23

x24

Demand

900

400

500

200

4

Chandrapur

8

x12

6

Dummy Destination

7

x13

4

Supply

0

x14

3

1000

0

1000

2.3 Steps in Solution Process

The transportation problem can be solved with exact steps of the simplex method.

But special structure of transportation problem gives an advantage. We can directly

solve transportation problem without going for complex computations of simplex

method.

Following steps are used in solving a transportation problem.

1.

Formulate the problem and arrange the data in matrix form as shown in table 2.

2.

Detemine a starting basic feasible solution. Following three methods can be

used to get initial basic feasible solution.

North- West Corner Method (N-W-C Method)

Least Cost Method (LC Method)

Vogel's Approximation Method (VAM)

3.

Test initial solution for optimality. If the optimality condition is satisfied stop,

otherwise determine the entering variable from among all the nonbasic variables

and go to step 4.

4.

Use the feasibility condition to determine the leaving variable from among the

current basic variables and find the new basic solution. Return to step 3, till

optimality is reached.

2.3.1 Initital Basic Feasible Solution : (IBFS)

The IBFS or any feasible solution must satisfy all the supply and demand

conditions. If m sources and n destination are shown in a model, it must have m +n -l

allocations, i.e. basic variables.

[Please note that all cells of transportation table will not have positive allocations

only m + n -1 cells will have allocations.]

1.

Northwest Corner Method

N-C method is the simplest method to get a starting solution. However it can not

provide a high quality starting solution. The initial value of objective function is relatively

higher as compared to other methods to get starting solution.

The method starts from the northwest- corner cell of the table.

Quantitative Techniques in

Management : 36

1

Consider table 2, we will all allocate

900 units in the Northwest- corner cell.

1

3

supply

4

8

7

1000

100

6

4

3

800

900

This will complete allocations of

column 1 and supply from row 1 is reduced