Ulnar Collateral Ligament Reconstruction in Major League Baseball Pitchers

advertisement

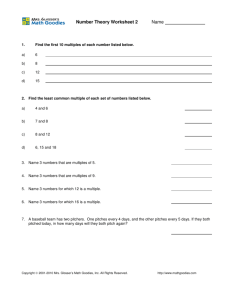

Ulnar Collateral Ligament Reconstruction in Major League Baseball Pitchers Brett W. Gibson, MD, David Webner, MD, G. Russell Huffman, MD, MPH, and Brian J. Sennett, MD From the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Penn Sports Medicine Center, Division of Sports Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Background: Ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction is commonly performed in major league pitchers, but little is known about pitching performance after a return to major league play. Hypothesis: Pitching performance after ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction returns to baseline by the second season after surgery. Study Design: Cohort study (prognosis); Level of evidence, 2. Methods: Data were reviewed for 68 major league pitchers who pitched in at least 1 major league game before undergoing ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction between 1998 and 2003. Mean innings pitched per season, earned run average, and walks and hits per inning pitched were compared for each major league pitcher before and after surgery. All demographic and performance variables were analyzed for an association with ulnar collateral ligament insufficiency and a successful return to major league play. Results: Fifty-six (82%) pitchers returned to major league play at a mean of 18.5 months after surgery with no significant change in mean earned run average or walks and hits per inning pitched. The mean innings pitched per season was not statistically different from controls by the second season after surgery. Starting pitchers demonstrated a higher risk of ulnar collateral ligament injury requiring reconstruction. More experienced pitchers and those with a higher earned run average were less likely to require ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction. No factors predictive of a successful return to play were identified. Conclusion: Most major league pitchers return from ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction by the second season after surgery with no statistical change in mean innings pitched, earned run average, or walks and hits per inning pitched from preinjury levels. Keywords: elbow; ulnar collateral ligament; injury; pitcher; overuse “Tommy John surgery.” Today, UCL reconstruction is commonly performed for overhead athletes with UCL injury. Several published case series have described the results of UCL reconstruction.1-3,7,13,15,18,19 Few have dealt exclusively with major league pitchers, and little is known about potential risk factors for injury requiring reconstruction or factors contributing to a successful return to play in this patient population. Additionally, little is known about the performance of pitchers who return to major league play after UCL reconstruction. The purpose of this study is to describe the results of UCL reconstruction in major league pitchers, to compare the performance of these pitchers before and after surgery, and to identify risk factors for undergoing UCL reconstruction and factors associated with a successful return to major league play. The primary stabilizer to valgus stress of the elbow is the anterior oblique bundle of the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL).9-12,14,16,17 Valgus stress on the medial elbow occurs during the late cocking and acceleration phases of the overhead throwing motion. The anterior bundle of the UCL is subject to high tensile stress during the acceleration phase of throwing that may eventually lead to ligament attenuation or failure.4-6,9-12,14,16,19 Ulnar collateral ligament insufficiency is common among baseball pitchers and other overheadthrowing athletes. Historically, rupture of the UCL was career-ending. In 1974, Jobe performed the first reconstruction of the anterior band of the UCL on Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher Tommy John. Tommy John proceeded to win 164 games after the procedure, which has since been dubbed *Address correspondence to Brett W. Gibson, MD, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Penn Sports Medicine Center, Division of Sports Medicine, 235 S. 33rd Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104-4405 (e-mail: brett.gibson@uphs.upenn.edu). No potential conflict of interest declared. MATERIALS AND METHODS Reconstructed Pitchers Data were reviewed for 68 major league pitchers who pitched in at least 1 major league game before undergoing UCL reconstruction. No pitchers appeared in only 1 game The American Journal of Sports Medicine, Vol. 35, No. 4 DOI: 10.1177/0363546506296737 © 2007 American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine 575 576 Gibson et al before reconstruction, and most pitchers appeared in several games during multiple seasons. Reconstructed pitchers were identified from team injury reports and press releases indicating that the pitcher underwent UCL reconstruction. “Tommy John surgery” was considered an acceptable reference to UCL reconstruction. Article XIII Section C of the Major League Baseball Players Association Collective Bargaining Agreement provides standards for injury reporting in major league baseball, stating that the “Application by a Club to the Commissioner to place a Player on the Disabled List shall be accompanied by a Standard Form of Diagnosis” to be completed by the team physician. The Standard Form of Diagnosis includes fields for UCL injury and surgery in the arm/elbow diagnosis description. The physician and a club official are required to sign the completed form before submission to the Commissioner. These standards ensure a high degree of reliability for major league baseball injury reports as a primary source of identifying the study population. Surgery was performed between 1998 and 2003. Age and major league pitching experience were determined at the time of UCL reconstruction. Height, weight, throwing handedness, and pitching role (starting or relief pitcher) were recorded for each reconstructed pitcher. Body mass index was calculated from height and weight data. The date of return to major league play was recorded, and the time to return was calculated. The month of surgery was not available for 1 subject who successfully returned to major league play. The innings pitched, earned run average (ERA), and walks and hits per inning pitched (WHIP) during major league play were recorded for each reconstructed pitcher during 7 consecutive seasons. Earned run average represents the average number of earned runs allowed per 9 innings pitched, or 1 complete major league game. An earned run is any run scored by the opposing team for which the pitcher is held accountable. Runs scored as a result of fielding errors, including those by the pitcher himself, or passed balls are considered unearned and are excluded from the calculation. Walks and hits per inning is determined by dividing the sum of walks and hits by the total number of innings pitched. The average during 3 consecutive seasons before the index year was defined as the subject’s preindex performance. The average during 3 consecutive seasons after the index year was defined as the pitcher’s postindex performance. Data from the index season were excluded from both calculations. Control Pitchers A control group is necessary to define expected levels of performance in major league pitchers during the course of 7 seasons. Every fifth name was selected from a complete alphabetical roster of major league pitchers from the 2001 season for a total of 112 pitchers in the control group. The 2001 major league season was defined as the index year for this cohort. Players with a known history of UCL reconstruction were excluded from this list before selection. Pitchers were not excluded from the control group on the basis of any other injuries or surgical procedures. The American Journal of Sports Medicine Age and major league pitching experience were determined at opening day in 2001. Height, weight, throwing handedness, and pitching role (starting or relief pitcher) were recorded for each control pitcher. Body mass index was calculated from height and weight data. Preindex and postindex performance averages were calculated as described for reconstructed pitchers. Statistical Methods Paired analysis of preindex and postindex performance measures was performed for each major league pitcher in the reconstructed and control groups. Performance measures were compared between reconstructed and control groups on a seasonal basis to better account for the expected decline in innings pitched among reconstructed pitchers during the recovery period. Age, experience, height, weight, body mass index, throwing handedness, pitching role, and preindex performance measures were then analyzed for an association with risk of UCL injury requiring reconstruction and a successful return to major league play. The Student t test was used to compare age, experience, height, weight, body mass index, and performance measures between groups. Paired means testing was used to assess preindex and postindex performance measures within each group of pitchers. The Fisher’s exact probability test was used to compare throwing handedness and pitching role between groups. Both univariate and multivariate statistical analyses were performed using STATA 8.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas). RESULTS Player Characteristics Player characteristics are presented in Table 1. Sixty-eight reconstructed pitchers and 112 control pitchers were included in the study. The mean age was 28.2 years (range, 22-42 years) for reconstructed pitchers and 29.1 years (range, 21-44 years) for controls (P = .26). The mean major league experience was 5.1 years (range, 1-18 years) for reconstructed pitchers and 5.9 years (range, 1-22 years) for controls (P = .26). Thirty-nine reconstructed pitchers (57%) were starting pitchers compared with 40 (36%) control pitchers (P = .005). By comparison, 232 major league pitchers (38 percent) in 2005 were starting pitchers, which is not statistically different from the control group (P = .67). No statistical difference in height, weight, body mass index, or throwing handedness was identified between the reconstructed and control groups (Table 1). The preindex average innings pitched per season was 92.98 for reconstructed pitchers and 87.11 for controls (P = .58). The preindex mean ERA was 4.16 for reconstructed pitchers and 4.37 for controls (P = .03). The preindex mean WHIP was 1.362 for reconstructed pitchers and 1.384 for controls (P = .04). The mean innings pitched, ERA, and WHIP for the control group was statistically representative of the mean for Vol. 35, No. 4, 2007 UCL Reconstruction in Major League Baseball Pitchers TABLE 1 Reconstructed and Control Pitcher Characteristics Seasonal Comparison 140.00 Reconstructed Control UCL Reconstruction (n = 68) Control (n = 112) P Value 28.2 ± 0.4 5.1 ± 0.1 29.1 ± 0.3 5.9 ± 0.1 .26 .26 Age (years) Major league experience (seasons) Height (m) Weight (kg) Body mass index % Right-handed pitchers % Starting pitchers Innings Pitched 120.00 Player Characteristic 577 100.00 * 80.00 ** 60.00 40.00 20.00 0.00 −3 1.89 ± 0.03 95.6 ± 1.4 26.9 ± 0.4 1.88 ± 0.02 94.7 ± 0.8 26.8 ± 0.2 .58 .54 .73 78% 74% .60 57% 36%a .005 a 38% of major league baseball pitchers in 2005 were starting pitchers. all major league pitchers who played during the 2001 major league baseball season. The overall league average was calculated using the total innings pitched and the total earned runs, walks, and hits allowed for all 622 major league pitchers in 2001. The mean performance measures for the control group during the index year were within 2.4% of the calculated league average. Return to Major League Pitching Fifty-six (82%) reconstructed pitchers returned to major league play at a mean of 18.5 months (range, 10-49 months) after surgery. Reconstructed pitchers were observed for an average of 4.3 years (range, 2-8 years). No reconstructed pitchers returned to major league play during the index year. Thirty-two (47%) reconstructed pitchers returned to major league play during the first postindex season. Fifty (74%) reconstructed pitchers returned to major league play by the second postindex season. Fifty-three (78%) reconstructed pitchers returned to major league play by the third postindex season. The remaining 3 reconstructed pitchers returned to major league play greater than 3 years after the index year. Player Performance Fifty-four reconstructed pitchers and 70 control pitchers were available for paired analysis of preindex and postindex performance measures. Preindex averages could not be calculated for 1 reconstructed pitcher and 23 control pitchers who did not appear in any major league games before the index year. Postindex averages could not be calculated for 12 reconstructed pitchers who failed to return to major league play after surgery, 3 reconstructed pitchers who returned more than 3 seasons after the index year, and 13 control pitchers with no major league appearances during the postindex period. Neither preindex nor postindex −2 −1 0 Season 1 2 3 Figure 1. Comparison of innings pitched by individual season between reconstructed pitchers and controls. Season 0 represents the index year. *P = .06; **P < .05. averages could be calculated for 6 control pitchers who played during the index year only. Paired analysis of reconstructed pitchers revealed that innings pitched per season decreased significantly from a preindex mean of 97.10 (range, 6.00-234.56) to 70.17 (range, 2.00-198.00) after the index year (P = .003). Control pitchers also demonstrated a significant decrease in innings pitched per season from a preindex mean of 94.73 (range, 1.00-246.44) to 79.29 (range, 4.00-238.22) after the index year (P = .02). The ERA for reconstructed pitchers demonstrated no significant change from a preindex mean of 4.12 (range, 0.00-11.37) to 4.21 (range, 0.00-8.24) after the index year (P = .14). Similarly, control pitchers demonstrated no significant change in ERA from a preindex mean of 4.34 (range, 0.00-13.48) to 4.27 (range, 2.19-15.75) after the index year (P = .47). The WHIP for reconstructed pitchers showed no significant change from a preindex mean of 1.362 (range, 1.000-2.422) to 1.356 (range, 0.500-1.958) after the index year (P = .83). Control pitchers also demonstrated no significant change in WHIP from a preindex mean of 1.376 (range, 0.922-2.622) to 1.349 (range, 0.795-2.750) after the index year (P = .97). The average innings pitched per season was compared between reconstructed and control pitchers for each of the 7 seasons evaluated in this study (Figure 1). Innings pitched was not statistically different between reconstructed and control groups in any of the 3 preindex seasons (P = .58, P = .58, and P = .77, respectively). During the index year, the mean innings pitched was 50.80 for reconstructed pitchers and 72.25 for controls (P = .06). Only 6 pitchers in the reconstructed group completed a full season during the index year before undergoing surgery. During the first postindex season, the mean innings pitched was 44.91 for reconstructed pitchers who had successfully returned to major league play and 82.98 for controls (P = .001). Of the 32 reconstructed pitchers who returned during the first postindex season, 13 (41%) missed at least half of the season. In the second and third postindex seasons, the mean innings pitched among reconstructed pitchers was not statistically different from control pitchers (P = .71 and P = .76, respectively). The mean ERA between cohorts was similarly compared (Figure 2). In the first and second preindex seasons, no 578 Gibson et al The American Journal of Sports Medicine Seasonal Comparison Seasonal Comparison 6.00 5.50 Reconstructed Control 1.500 1.450 5.00 * WHIP ERA 1.550 Reconstructed Control 4.50 * 1.400 4.00 1.350 3.50 1.300 1.250 3.00 −3 −2 −1 0 Season 1 2 -3 3 Figure 2. Comparison of ERA by individual season between reconstructed pitchers and controls. Thirty-nine reconstructed pitchers played during the index year (Season 0). *P < .05. statistical difference was found in the mean ERA for reconstructed and control pitchers (P = .83 and P = .19, respectively). During the third preindex season (1 season before the index year), the mean ERA for reconstructed pitchers (4.19) was significantly better than the mean ERA for control pitchers (4.54, P = .01). During the index year, the mean ERA was 5.20 for reconstructed pitchers and 4.45 for controls, but this difference was not statistically significant (P = .92). No statistical difference was found in the mean ERA for reconstructed and control pitchers in any of the 3 postindex seasons (P = .31, P = .18, and P = .69, respectively). The mean WHIP for reconstructed and control pitchers is presented in Figure 3. In the first and second preindex seasons, no statistical difference was found in the mean WHIP for reconstructed and control pitchers (P = .89 and P = .43, respectively). During the third preindex season (1 season before the index year), the mean WHIP for reconstructed pitchers (1.368) was significantly better than the mean WHIP for control pitchers (1.417, P = .007). During the index year, the mean WHIP for reconstructed pitchers was 1.489 compared with 1.361 for controls, but this difference was not statistically significant (P = .48). No statistical difference was found in the mean WHIP for reconstructed and control pitchers in any of the 3 postindex seasons (P = .11, P = .12, and P = .84, respectively). Risk Factors for UCL Reconstruction Univariate analysis (Table 2) demonstrated a significantly increased risk of undergoing UCL reconstruction among starting pitchers (odds ratio [OR] = 2.42, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.31-4.48, P = .005). A significant association was also observed for preindex ERA (OR = 0.80 per earned run, 95% CI 0.65-0.99, P = .04) and preindex WHIP (OR = 0.25 per unit, 95% CI 0.07-0.97, P = .05) with reduced odds for undergoing UCL reconstruction. Comparison of preindex performance measures between starting and relief pitchers revealed that starters averaged significantly more innings pitched per season (130.00 vs 59.00, P < .001) with a superior WHIP (1.391 vs 1.484, P = .05). The mean ERA was not statistically different between starters (4.44) and relievers (4.60, P = .63). Linear regression -2 -1 0 Season 1 2 3 Figure 3. Comparison of WHIP by individual season between reconstructed pitchers and controls. Thirty-nine reconstructed pitchers played during the index year (Season 0). *P < .05. TABLE 2 Univariate Analysis of Risk Factors for Pitchers Undergoing UCL Reconstruction Player Characteristic Age Major league experience Starting pitcher Right-handed pitcher Mean innings pitched Mean earned run average Mean walks and hits per inning pitched Odds Ratio (95% CI) P Value 0.96 0.96 2.42 1.23 1.00 0.80 0.25 0.90-1.03 0.90-1.03 1.31-4.48 0.60-2.52 0.97-1.01 0.65-0.99 0.07-0.97 .280 .259 .005 .562 .577 .037 .045 analysis demonstrated a significant association between major league experience and preindex performance measures as well. The mean innings pitched was 4.79 innings higher per year of major league experience (P < .001). The mean WHIP was 0.012 units lower per year of major league experience (P = .03). The mean ERA was 0.05 earned runs lower per year of major league experience, but this was not a statistically significant association (P = .13). Since these factors are potential confounding variables, a multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed. Multivariate analysis adjusting for all demographic and performance variables, including age, major league experience, BMI, throwing handedness, pitching role, and preindex performance measures, revealed that the only significant risk factor for undergoing UCL reconstruction was being a starting pitcher (OR = 2.62, 95% CI 1.03-6.67, P = .04). In a backward stepwise multivariate logistic regression analysis (Table 3) excluding variables with a greater than 10% probability of an association by chance alone (P > .10), only starting pitching was associated with an increased likelihood of undergoing UCL reconstruction (OR = 2.45, 95% CI 1.21-4.98, P = .01), while major league experience (OR = 0.88 per year, 95% CI 0.80-0.95, P = .002) and a higher preindex ERA (OR = 0.76 per earned run, 95% CI 0.61-0.95, P = .02) were both associated with a significantly decreased likelihood of undergoing the procedure. Vol. 35, No. 4, 2007 UCL Reconstruction in Major League Baseball Pitchers TABLE 3 Backward Multivariate Stepwise Logistic Regression Analysis of Risk Factors for Pitchers Undergoing UCL Reconstruction, Beginning With All Variables and Eliminating Factors With P > .10 in a Stepwise Fashion Player Characteristic Major league experience (per year) Starting pitcher Mean earned run average Odds Ratio (95% CI) P Value 0.88 0.80-0.95 .002 2.45 0.76 1.21-4.98 0.61-0.95 .013 .018 Factors Predicting Successful Return to MLB Univariate analysis identified no significant factors predictive of a successful return to major league play among reconstructed pitchers (Table 4). Similarly, multivariate analysis adjusting for all demographic and performance variables revealed no significant factors associated with a successful return to major league play. DISCUSSION Jobe7 first reported his results for UCL reconstruction in throwing athletes in 1986. Ten of 16 (63%) patients returned to the same level of play with a minimum 2-year follow-up. Conway et al3 reported on a series of 56 patients with 2- to 15-year (mean, 6.3 years) follow-up after UCL reconstruction. Thirty-eight (68%) successfully returned to sports, including 12 of 16 (75%) major league baseball players with no prior elbow procedures. Andrews and Timmerman19 reported that 12 of 14 (86%) athletes treated with UCL reconstruction returned to play. More recently, Azar et al2 reported on 59 throwing athletes who underwent UCL reconstruction with 12- to 72-month (mean, 35.4 months) follow-up. Forty-eight (81%) returned to play at an average of 9.8 months after surgery. Thompson et al18 published a series on 33 athletes with 2- to 4-year follow-up. Twenty-seven (82%) were able to return to their previous level of play. Rohrbough et al15 reported that 33 of 36 (97%) patients undergoing UCL reconstruction successfully returned to play at 2- to 5-year (mean, 3.3 years) follow-up, including all college or professional athletes. The study group included 33 baseball players, 1 lacrosse player, 1 tennis player, and 1 golfer. Twenty-seven baseball players were pitchers, and 9 were professional baseball pitchers (4 major league). In 2004, Petty et al13 reported the results of UCL reconstruction in 27 high school baseball players, 24 of whom were pitchers. Twenty (74%) returned to play at or above their preinjury level at an average of 11 months postoperatively. No previously reported studies have dealt exclusively with the results of UCL reconstruction in major league pitchers, an elite group of throwing athletes. The rate of return in this series (82%) was comparable to that in more 579 TABLE 4 Univariate Analysis of Factors Associated With Successful Return to Major League Baseball Pitching After UCL Reconstruction Player Characteristic Age Major league experience Relief pitcher Right-handed pitcher Mean innings pitched Mean earned run average Mean walks and hits per inning pitched Odds Ratio (95% CI) P value 0.99 1.04 0.86-1.15 0.89-1.22 .990 .602 1.61 1.22 1.00 1.05 4.76 0.43-5.98 0.28-5.23 0.99-1.02 0.71-1.56 0.16-144.60 .475 .787 .415 .812 .370 recently published series. The mean time to return in this population (18.5 months) was longer than previously reported averages,2,13 with 3 pitchers requiring more than 3 seasons to return. In cases of prolonged delays in return to play, nonbiologic factors are presumed to play a role, including substandard pitching performance in minor league assignments and the major league roster’s limited capacity to accommodate additional pitchers. In all recently published series of UCL reconstruction, success was determined by a return to the same level of play for at least 1 year. This measure as originally described by Conway et al3 is thought to control for subjective performance bias by considering only the achievable level and duration of competition. Innings pitched, ERA, and WHIP represent additional objective measures for baseball pitchers that have not been previously considered. In the present study, pitchers who successfully returned to major league play after UCL reconstruction experienced no significant decline from preindex performance. The average innings pitched among reconstructed pitchers reached control levels by the second season after surgery. Both reconstructed and control pitchers experienced a significant decline in innings pitched during the postindex period. The decline in innings pitched among control pitchers may represent missed games due to other injuries or an expected decline in games played as some pitchers retire. Other control pitchers might fail to meet the standards of major league play and lose time to more promising prospects. Most reconstructed pitchers who returned during the first postindex season failed to play a full season, resulting in statistically fewer innings pitched when compared with controls. The mean ERA and WHIP among reconstructed pitchers, both of which are weighted performance measures and therefore may represent better indicators of performance than innings pitched, were not statistically different from controls by the first season after surgery. Very little is known about risk factors for UCL insufficiency. Overuse was implicated as a primary risk factor for development of UCL insufficiency in a recent series of high school baseball pitchers.13 A significantly higher proportion of pitchers in this study’s UCL reconstruction cohort 580 Gibson et al were starting pitchers compared with the nonreconstructed (control) cohort. Starting pitchers demonstrated a significantly higher likelihood of undergoing UCL reconstruction on both univariate and multivariate analyses. While limited conclusions about risk may be ascertained from observational studies, this finding appears to support the concept of overuse as a risk factor for injury. Starting pitchers average more innings pitched per season and per game than relief pitchers, placing greater demands on the throwing elbow and making them more susceptible to UCL injury. No significant association between preindex innings pitched and UCL reconstruction was found on either univariate or multivariate analysis. On univariate analysis, a higher likelihood of undergoing UCL reconstruction was found among pitchers with better weighted performance measures, that is, lower ERA and WHIP, during the preindex seasons. After controlling for potential confounding factors, a better preindex ERA and fewer years of major league experience were associated with an increased risk of undergoing UCL reconstruction. The style of pitching required to achieve a lower ERA, including elevated pitch speed and increased number of breaking pitches thrown, might explain the higher rate of UCL injury in this population. More experienced pitchers might demonstrate superior pitching mechanics that are protective with regard to injury, with this improved durability translating into longer major league careers. Younger pitchers might choose to ignore early signs of UCL insufficiency and play through the pain, resulting in more severe injury over time. Finally, older pitchers faced with UCL reconstruction might elect to retire rather than endure the prolonged recovery time inherent in this procedure. Univariate and multivariate analyses of potential factors contributing to a successful return to major league play yielded no statistically significant results. Since relatively few pitchers fail to return, large numbers of reconstructed pitchers are required to achieve statistical significance. Relief pitchers might enjoy an advantage over starting pitchers given the lower demands placed on the throwing elbow in terms of innings pitched per game. This series demonstrated a trend toward more successful return to play among relief pitchers, including 5 starting pitchers who returned to major league play as relief pitchers, but this difference was not statistically significant. A more successful return to major league play might be related to unobserved factors such as surgeon experience, the method of ligament reconstruction employed, or transposition of the ulnar nerve at the time of reconstruction. Limitations of the current study include the potential for bias, confounding, and chance inherent in all observational studies. In this report, potential sources of bias include missing data (information bias) that is unobtainable from injury reports. We may not, in fact, be capturing all major league pitchers undergoing UCL reconstruction during the study period. In doing so, we may not be able to correctly infer as to the performance, rate of return to pitching, and potential risk factors for undergoing UCL reconstruction. Anecdotally, UCL reconstruction is perceived favorably among major league baseball players, with some major league pitchers The American Journal of Sports Medicine claiming that ball velocity and movement of breaking pitches actually improve from preoperative levels after surgery. For this reason, players and teams have little motivation to misreport UCL injury compared with, for example, rotator cuff injuries requiring repair, which have demonstrated much poorer results in this population.8 Confounding, or associations between risk factors for an outcome and between 2 or more risk factors, is also possible in this type of analysis leading to incorrect assumptions regarding associations of risk when they do not exist. To control for confounding, one may perform an experimental clinical study (randomized, prospective clinical trial), but this is not possible when assessing risk. Alternatively, one may minimize confounding by accounting for potential associated factors using multivariate analysis as performed in this study. Chance occurs when the probability of an association occurs randomly. In an observational study, one may control for chance only by selecting an acceptably stringent level of significance. In the present study, the significance of starting pitchers having an increased likelihood of undergoing UCL reconstruction was .005, or 5 in 1000 by chance alone. After controlling for other potentially confounding factors, the chance of this association persisting by chance alone remained low at 13 in 1000 (P = .013). In conclusion, the present study suggests that most major league pitchers return from UCL reconstruction by the second season after surgery with no discernable change in mean innings pitched, ERA, or WHIP from preinjury levels. Starting pitchers are more likely to undergo UCL reconstruction but return to major league play at a rate not statistically different from that of relief pitchers. Pitchers with a lower preindex ERA or fewer years of major league experience also demonstrated an increased risk of UCL injury requiring reconstruction. No factors predictive of a successful return to play were identified in this study. REFERENCES 1. Andrews JR, Timmerman LA. Outcome of elbow surgery in professional baseball players. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23:407-413. 2. Azar FM, Andrews JR, Wilk KE, Groh D. Operative treatment of ulnar collateral ligament injuries of the elbow in athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28:16-23. 3. Conway JE, Jobe FW, Glousman RE, Pink M. Medial instability of the elbow in throwing athletes: treatment by repair or reconstruction of the ulnar collateral ligament. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74:67-83. 4. Dillman CJ, Fleisig GS, Andrews JR. Biomechanics of pitching with emphasis upon shoulder kinematics. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1993;18:402-408. 5. Fleisig GS, Andrews JR, Dillman CJ, Escamilla RF. Kinetics of baseball pitching with implications about injury mechanisms. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23:233-239. 6. Hotchkiss RN, Weiland AJ. Valgus stability of the elbow. J Orthop Res. 1987;5:372-377. 7. Jobe FW, Stark H, Lombardo SJ. Reconstruction of the ulnar collateral ligament in athletes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68:1158-1163. 8. Mazoue CG, Andrews JR. Repair of full-thickness rotator cuff tears in professional baseball players. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:182-189. 9. Morrey BF. Applied anatomy and biomechanics of the elbow joint. Instr Course Lect. 1986;35:59-68. 10. Morrey BF, An KN. Articular and ligamentous contributions to the stability of the elbow. Am J Sports Med. 1983;11:315-319. Vol. 35, No. 4, 2007 UCL Reconstruction in Major League Baseball Pitchers 581 11. Morrey BF, An KN. Functional anatomy of the ligaments of the elbow. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1985;201:84-90. 12. Morrey BF, Tanaka S, An K. Valgus stability of the elbow. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;265:187-195. 13. Petty DH, Andrews JR, Fleisig GS, Cain EL. Ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction in high school baseball players: clinical results and injury risk factors. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:1158-1164. 14. Regan WD, Korinek SL, Morrey BF, An KN. Biomechanical study of ligaments around the elbow joint. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;271: 170-179. rd 15. Rohrbough JT, Altchek DW, Hyman J, Williams RJ 3 , Botts JD. Medial collateral ligament reconstruction of the elbow using the docking technique. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30:541-548. 16. Schwab GH, Bennett JB, Woods GW, Tullos HS. Biomechanics of elbow instability: the role of the medial collateral ligament. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1980;146:42-52. 17. Søjbjerg JO, Ovesen J, Nielsen S. Experimental elbow instablitity after transection of the medial collateral ligament. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;218:186-190. 18. Thompson WH, Jobe FW, Yocum LA, Pink MM. Ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction in throwing athletes: muscle-splitting approach without transposition of the ulnar nerve. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10:152-157. 19. Timmerman LA, Andrews JR. Histology and arthroscopic anatomy of the ulnar collateral ligament of the elbow. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22: 667-673.