Postoperative Rehabilitation Protocols for Achilles Tendon Ruptures A Meta-analysis

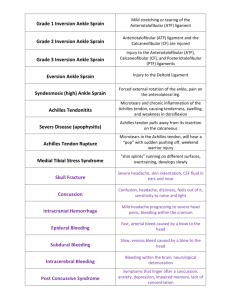

advertisement

CLINICAL ORTHOPAEDICS AND RELATED RESEARCH Number 445, pp. 216–221 © 2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Postoperative Rehabilitation Protocols for Achilles Tendon Ruptures A Meta-analysis Amar A. Suchak, MD; Carol Spooner, MSc; David C. Reid, FRCS(C); and Nadr M. Jomha, FRCS(C) cises.2 Small prospective human clinical trials13,17,18 used early functional protocols involving weightbearing as early as the first postoperative day, with early ROM and splinting in a walking boot or modified orthosis instead of a cast. These studies had good patient satisfaction reported with a low rate of reruptures and infections. Experimental rat research also showed that weightbearing when compared with immobilization after Achilles tendon rupture repair results in a stronger tendon with a greater force required for a rerupture to occur.5,15,16 Therefore, there is preliminary evidence to support the introduction of an early functional protocol for postoperative Achilles tendon rupture repair. Unfortunately, the majority of the published clinical trials that document advantages of an early functional protocol do not have control groups for comparison, making it difficult to determine if this is better than the current accepted standard treatment. In addition, small numbers of patients enrolled in these studies provide insufficient assurance that there are no increased risks associated with early functional protocols. Therefore, it is difficult to implement an early functional protocol as the standard of care for the general population of patients with acute surgically treated Achilles tendon rupture. We determined from prospective, randomized (or quasirandomized) controlled trials whether an early functional protocol compared with cast immobilization for surgical repair of an acute Achilles tendon rupture improved subjective patient satisfaction without an increase in rerupture rate. Secondary outcomes compared among the two protocols included infection rate, ROM, calf strength, and minor surgical complications. The optimal postoperative rehabilitation protocol after surgical repair of an Achilles tendon rupture is unknown. Although a 6-week cast immobilization is common, many early functional rehabilitation protocols have been implemented. The purpose of this study was to conduct a meta-analysis to determine if an early functional protocol for surgical repair of an acute Achilles tendon rupture improves subjective patient satisfaction without an increase in rerupture rates. Secondary outcomes of interest from an early functional protocol include infections, range of motion, strength, and minor complications. An extensive literature search for randomized or quasirandomized studies identified six trials involving 315 patients. Early functional treatment protocols, when compared with postoperative immobilization, led to more excellent rated subjective responses and no difference in rerupture rate. Our conclusions are based on six trials with small sample sizes, and larger randomized trials are required to confirm these results. Level of Evidence: Therapeutic Study, Level II (Systematic review of Level II studies or Level I studies with inconsistent results). See the Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence. The optimal postoperative rehabilitation protocol after surgical repair of an Achilles tendon rupture is evolving from the classic routine using rigid immobilization in a belowknee nonweightbearing cast for 6 weeks with subsequent ankle range of motion (ROM) and strengthening exerReceived: January 14, 2005 Revised: May 26, 2005; October 17, 2005 Accepted: December 1, 2005 From the Department of Surgery, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. Each author certifies that he or she has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article. Correspondence to: Dr. Nadr Jomha, #1002, 8215-112th Street, College Plaza, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T6G 2C8. Phone: 780-434-3668; Fax: 780-434-4859; E-mail: nadr@interbaun.com. DOI: 10.1097/01.blo.0000203458.05135.74 MATERIALS AND METHODS A systematic literature review for randomized controlled trials that compared early functional protocols with immobilization regimens for Achilles tendon ruptures was performed specifically identifying studies that documented patient satisfaction and rerupture rates. Articles were included if they met the following 216 Number 445 April 2006 criteria: (1) prospective randomized or quasirandomized controlled trials; (2) trials enrolling adults (ⱖ 18 years of age) diagnosed with an acute rupture of the Achilles tendon; (3) trials that compared a control group assigned to a standard immobilization and delayed weightbearing regimen with a treatment group assigned to an early functional protocol for postoperative management of a surgically repaired acute Achilles tendon rupture; and (4) subjective patient satisfaction, reruptures, infections, minor surgical complications, and functional measures (eg, plantar flexion function strength). A librarian experienced in systematic review searching assisted with the following search strategy: Achilles tendon AND (rupture* or torn or tear*) AND (rehab* OR repair* OR operati* OR postoperati* OR sutur* OR surg* OR mobili* OR immobili* OR wrap* OR brace* OR weightbear* OR weight bear* OR walking cast*) (* indicates truncation). The Ovid Medline database January 1966 to July 2004, Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) 1982 to July 2004, EMBASE 1988 to 2004 Week 28, The Physiotherapy Evidence Database (online PEDro), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects were searched. In addition, a Web of Science cited reference search was done based on the citations selected for inclusion. The search results were reviewed by two independent reviewers (AS, NJ) using a priori inclusion and exclusion criteria. The article quality was assessed by evaluating components of the study design including randomization, blinding, population, intervention, and outcomes. Interreviewer qualitative statistical analysis for these components was not done. Differences were resolved by discussion. Eighty-four titles and abstracts potentially relevant to the review were retrieved (20 from Medline, 17 from EMBASE, 27 from CINAHL, 20 from the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials Cochrane, and none from PEDro). After limiting for prospective, controlled, human trials and overlap from the search engines, only eight eligible trials remained. Two studies were eliminated based on outcome criteria: one was focused on neuromotor function (as opposed to objective and subjective clinical outcomes) and did not include postoperative complication data,8 and the other did not follow a standard immobilization regimen and failed to provide adequate objective results such as plantar flex- Fig 1. A comparison of the excellent satisfaction patient response for both rehabilitation regimes is shown. More patients reported excellent satisfaction with an early functional routine. Maffulli a10; Maffulli b11 Meta-analysis of Tendon Rupture Protocols 217 ion strength or ROM.9 Therefore, six trials2,3,7,10–12 met all the inclusion criteria. Although each study had slight differences in their methodology or outcomes, the I2 statistic (for evaluation of the extent of variability in results among the studies)6 for subjective patient satisfaction and rerupture rate (the two primary outcomes) was zero, which is suggestive of low heterogeneity, allowing for study comparison. Four studies2,3,7,12 used a randomized selection process, with the other two assigning therapy according to the day of the week.10,11 In four studies,2,3,10,11 it was reported that the individuals assessing the patients postoperatively were blinded to the treatment group. All studies had patients lost to followup. All trials used open surgical techniques, but varied with the commencement of weightbearing in the active early functional groups from 1 day to 6.5 weeks postoperatively. Corresponding authors were contacted, if possible,3,10–12 for additional specifics on data or methodology information that were not provided in the original paper. The studies recorded subjective patient data, reruptures, ankle ROM, ankle strength, and postoperative complications for each group, but not all studies measured identical outcomes. Different scoring scales were used to record patient satisfaction for each postoperative rehabilitation routine. To compare these different subjective scales, patient satisfaction data from each study were reclassified into excellent, adequate, or poor satisfaction groups (Fig 1). In all studies, rerupture and infection rates were reported. Four studies2,3,7,12 investigated ROM. Five studies2,3,10–12 examined gastrocnemius strength and calf circumference. Data were extracted and entered into Review Manager 4.2.2, a software program designed specifically for systematic reviews by the Cochrane Collaboration (Oxford, UK) and available online at http://www.cochrane.org/index0.htm. All calculations were made using a random effects model, as this model provides a more conservative summary estimate of treatment effect.14 For dichotomous data, the odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated for individual trials, and similar outcomes were combined to calculate a pooled estimate of effect, statistical significance, heterogeneity, and total events per group. Continuous data were combined using a weighted mean difference with 95% CI for individual and pooled estimates. Heterogeneity was tested using the Breslow-Day method and the I2 statistic.4 A p value < 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance. 218 Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research Suchak et al TABLE 1. Comparison of Study Characteristics Commencement of Partial Weightbearing Study Number of Subjects Mortensen et al12 1999 Maffulli et al10 2003 71 53 Costa et al3 2003 Cetti et al2 1994 Kangas et al7 2003 Maffulli et al11 2003 28 60 50 53 Randomization Method Computer-generated randomization Dependent on day of presentation Computer-generated random numbers in sequentially numbered opaque envelopes Method not stated Randomly mixed sealed envelopes Dependent on day of presentation RESULTS The six prospective controlled trials included 315 patients, 156 in the immobilization group and 159 in the early function group. The mean age of the patients was 40 ± 15 years. Of the 315 patients, 84% were men and 90% ruptured their Achilles tendon during a sporting event. The time until surgery varied in the immobilization group from 0 to 112 hours and in the early functional group from 0 to 508 hours. Commencement of partial weightbearing also varied among the studies (Table 1). Early functional treatment protocols led to more (p < 0.0001) excellent subjective responses when compared with postoperative immobilization (88% versus 62%, respectively) (Fig 1). The rerupture rate in the early functional treatment group was not different to that in the immobilized group (2.5% versus 3.8% respectively) (Fig 2). Ten reruptures occurred in 315 patients. No differences in superficial and deep infections occurred in the early functional treatment group (four infections) and immobilized group (six infections) during their postoperative rehabilitation (Fig 3). The average incisional infection rate was 2.6% in the early functional treatment group and 3.9% in the immobilized group. Fig 2. The rerupture rates in the early functional rehabilitation groups were compared rates in the immobilized groups. The odds ratio trends toward more reruptures occurring during an immobilized routine. Maffulli a10; Maffulli b11 Immobilized Group (Day) Early Motion Group (Day) 42 28 1 1 42 42 21 28 1 1 21 1 Other complications, including scar adhesions and transient sural nerve deficits, occurred less frequently (p ⳱ 0.01) (Fig 4) in the early functional treatment group (5.8%) than in the immobilized group (13.5%). Only one study2 found fewer (p ⳱ 0.02) patients with calf atrophy with an average of 0.7 cm larger (p ⳱ 0.02) calf circumference and better (p ⳱ 0.0006) plantar flexion strength in the early functional treatment group compared with the immobilized group. All other studies3,7,10–12 showed no difference between their groups. Only one study2 found a difference (p < 0.00001) in the degree of ROM in the early functional treatment group, with these patients having a 25º greater range after 6 weeks. DISCUSSION We report the first meta-analysis of randomized studies comparing an early functional protocol with the traditional postoperative protocols in acute Achilles tendon rupture repair. A meta-analysis was used because the current literature lacks appropriately conducted, large prospective, randomized clinical trials to determine if an early functional rehabilitation protocol improves patient satisfaction Number 445 April 2006 Meta-analysis of Tendon Rupture Protocols 219 Fig 3. The infection rates for each rehabilitation regimen were compared. There were no differences between the two groups. Maffulli a10; Maffulli b11 without an increase in rerupture rate. In addition, secondary outcomes, such as infection rates, gastrocnemius strength, and ROM were evaluated to determine other adverse effects of implementing an early functional protocol. This meta-analysis has certain limitations. There are only six studies available for comparison and not all of these studies were strictly randomized, although all were prospective. Two studies were included that had treatment groups determined by the day or the week the patient presented for treatment. These were included because trauma is a relatively random event and we could not identify a biasing factor leading patients to present on specific days or weeks. Each study used different rehabilitation routines. When classifying an early functional rehabilitation protocol, early ROM and type of weightbearing allowed early during the postoperative period were considered of prime importance. If either of these two factors Fig 4. A comparison of other postoperative complications occurring in each rehabilitation regimen is shown. The odds ratio revealed more complications occurred when an immobilized routine was used. Maffulli a10; Maffulli b11 was initiated in the immediate postoperative period, this was considered early functional rehabilitation when compared with traditional treatment. Finally, contacting all authors via phone or E-mail to discuss study specifics was largely unsuccessful. The subjective outcomes reported by patients after an early functional protocol were significantly better than outcomes of patients after a traditional rehabilitation protocol. In one study,2 two patients in the mobile cast group had previously ruptured the same Achilles tendon but were treated with a traditional rigid cast rehabilitation after their first injury. Both patients preferred the early functional protocol with a mobile cast because of “no edema of the leg in the cast period, the ability to weight bear and walk during the cast period, the ability to move the foot in a secure way immediately after the operation, and easier and faster ability to obtain normal gait after removal of the 220 Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research Suchak et al cast.”2 This meta-analysis strongly suggests that an early functional protocol can improve patient satisfaction after surgical repair of an acute Achilles tendon rupture. The rerupture rate after an early functional protocol is the same as after an immobilization protocol. Unfortunately, the details of the mechanisms of rerupture were not provided in all of the studies. A low postsurgical rerupture rate is in agreement with a review of Achilles tendon rupture management that compared (1) operative management with functional bracing, (2) nonoperative management with functional bracing, and (3) nonoperative management with immobilization.19 That study did not directly compare various aggressive rehabilitation protocols. The rerupture rates for these three groups were 1.4%, 1.5%, and 10.7%, respectively.19 These results provide confidence that an early functional rehabilitation protocol will not cause undue damage to the healing tendon. The early functional protocol group experienced fewer minor surgical complications, including infection rate, than the immobilized group. This is in agreement with a previous study, which compared open repair with early functional protocols with open repair with immobilization and nonoperative management of Achilles tendon ruptures, and concluded “overall, the best outcome with regard to complication rates was found in those patients managed with open repair and early mobilization.”19 Postoperative infections after operative treatment for Achilles tendon ruptures have been reported with a range of 4–20%.1 This is substantially greater than the pooled infection incidence reported in either group of the six studies in this meta-analysis. One explanation may be an improvement of surgical techniques in recent years, resulting in fewer complications as documented in this meta-analysis. The ankle ROM in both groups was comparable at 1 year. The increased ROM at 6 weeks in the mobile cast group2 is likely related to early timing of the measurement. Unfortunately, insufficient data for differences in ROM at 1 year postoperatively were provided in this study. Inconsistencies in data reporting among the six studies did not allow for a direct or statistical comparison of time to return to work and return to sport. In one study,11 it was reported that patients in the early functional group used less healthcare resources because of less physiotherapy and fewer cast changes. Also, this group of patients returned to work earlier than the immobilized group. Intuitively, an earlier weightbearing routine would allow a patient to return to a light duties routine at work and increased use of upper extremities for carrying purposes. The time to return to work and return to sport are important socioeconomic and psychosocial factors in evaluating new rehabilitation routines and are important to consider when designing studies to investigate new treatment regimens. An early functional rehabilitation protocol for Achilles tendon ruptures improves patient satisfaction with reduction in minor complications and no increase in rerupture rate or infection rate. Larger powered, prospective randomized studies are required to investigate the individual component of early weightbearing and early ROM to determine their effects on the outcome of Achilles tendon rupture repair and lead to dynamic rehabilitation protocols to improve patient satisfaction and clinical outcome. Acknowledgments We thank Mrs. J. Buckingham for help with the literature search, and Mrs. L. Beaupre for protocol support. References 1. Bhandari M, Guyatt GH, Siddiqui F. Morrow F, Busse J, Leighton RK, Sprague S, Schemitsch EH. Treatment of acute Achilles tendon ruptures: a systematic overview and metaanalysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;400:190–200. 2. Cetti R, Henriksen LO, Jacobsen KS. A new treatment of ruptured Achilles tendons: a prospective randomized study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;308:155–165. 3. Costa ML, Shepstone L, Darrah C, Marshall T, Donell ST. Immediate full-weight-bearing mobilisation for repaired Achilles tendon ruptures: a pilot study. Injury. 2003;34:874–876. 4. Deeks JJ AD. Bradburn MJ. Statistical Methods for Examining Heterogeneity and Combining Results From Several Studies in Meta-analysis. London, England: BMJ Publishing Group; 2001. 5. Enwemeka CS, Spielholz NI, Nelson AJ. The effect of early functional activities on experimentally tenotomized Achilles tendons in rats. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1988;67:264–269. 6. Hatala R, Keitz S, Wyer P, Guyatt G. Tips for learners of evidencebased medicine: 4. Assessing heterogeneity of primary studies in systematic reviews and whether to combine their results. Can Med Assoc J. 2005;172:661–665. 7. Kangas J, Pajala A, Siira P, Hamalainen M, Leppilahti J. Early functional treatment versus early immobilization in tension of the musculotendinous unit after Achilles rupture repair: a prospective, randomized, clinical study. J Trauma. 2003;54:1171–1180. 8. Kauranen K, Kangas J, Leppilahti J. Recovering motor performance of the foot after Achilles rupture repair: a randomized clinical study about early functional treatment vs. early immobilization of Achilles tendon in tension. Foot Ankle Int. 2002;23:600–605. 9. Kerkhoffs GM, Struijs PA, Raaymakers EL, Marti RK. Functional treatment after surgical repair of acute Achilles tendon rupture: wrap vs walking cast. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2002;122:102– 105. 10. Maffulli N, Tallon C, Wong J, Lim KP, Bleakney R. Early weightbearing and ankle mobilization after open repair of acute midsubstance tears of the achilles tendon. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:692– 700. 11. Maffulli N, Tallon C, Wong J, Peng Lim K, Bleakney R. No adverse effect of early weight bearing following open repair of acute tears of the Achilles tendon. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2003;43:367– 379. 12. Mortensen HM, Skov O, Jensen PE. Early motion of the ankle after operative treatment of a rupture of the Achilles tendon: a prospective, randomized clinical and radiographic study. J Bone Joint Surg. 1999;81:983–990. 13. Motta P, Errichiello C, Pontini I. Achilles tendon rupture. A new technique for easy surgical repair and immediate movement of the ankle and foot. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25:172–176. 14. Pettitti D. Meta-analysis, Decision Analysis, and Cost-effectiveness Analysis: Methods for Quantitative Synthesis in Medicine. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1994. 15. Qin L, Appell HJ, Chan KM, Maffulli N. Electrical stimulation Number 445 April 2006 prevents immobilization atrophy in skeletal muscle of rabbits. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997;78:512–517. 16. Rantanen J, Hurme T, Kalimo H. Calf muscle atrophy and Achilles tendon healing following experimental tendon division and surgery in rats: comparison of postoperative immobilization of the muscletendon complex in relaxed and tensioned positions. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 1999;9:57–61. 17. Solveborn SA, Moberg A. Immediate free ankle motion after sur- Meta-analysis of Tendon Rupture Protocols 221 gical repair of acute Achilles tendon ruptures. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22:607–610. 18. Troop RL, Losse GM, Lane JG, Robertson DB, Hastings PS, Howard ME. Early motion after repair of Achilles tendon ruptures. Foot Ankle Int. 1995;16:705–709. 19. Wong J, Barrass V, Maffulli N. Quantitative review of operative and nonoperative management of achilles tendon ruptures. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30:565–575.