Securitisation and the Commercial Property Cycle Frank Packer and Timothy Riddiough 1. Introduction

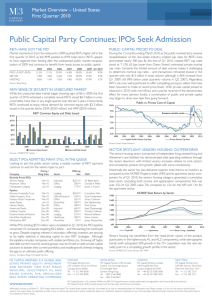

advertisement