Patterns and trends in Global savinG and investment ratios Introduction

advertisement

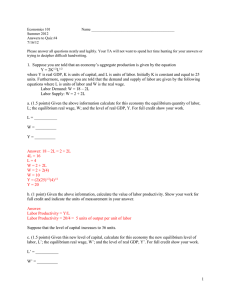

Patterns and trends in Global saving and Investment ratios Introduction There have been substantial changes in the size and distribution of current account balances around the world in recent decades. This article focuses on the differences in the saving and investment ratios of the major countries and emerging regions that have underpinned these changes. It shows that saving and investment ratios as a share of GDP have, for many decades, been much higher in Asia than in all other regions of the world, with persistent current account surpluses in Asia offsetting deficits in other areas. The article also shows that, in contrast to the early 2000s when the US current account deficit widened as the saving ratio fell, since the mid 2000s the investment and saving ratios in the United States have broadly moved commensurately, and hence the US current account deficit has been fairly stable as a share of GDP. The large increases in the current account surpluses of China and the oil exporters between 2005 and 2008 – as their saving ratios increased more than their investment ratios – have instead been associated with larger current account deficits in major countries and regions outside of the United States. The article concludes with a review of the near-term trends in these aggregates in light of the global recession. Average Saving and Investment Ratios in Major Countries and Regions Three identities underpin an analysis of world financial flows: a country’s current account balance equals the difference between its national saving and its investment; the sum of all the current account surpluses around the world equals the sum of the deficits; and, by implication, the level of world saving equals that of world investment. The global saving and investment ratio has varied over time (Graph 1). Saving and investment trended lower during the late 1990s and early 2000s, falling from around 22½ per cent of global GDP to a trough of 21 per cent in 2002, as declines in the saving and investment ratios of the United States and Japan were only partly offset by increases in the emerging economies. Thereafter, the global saving and investment ratio rose significantly, peaking at 24 per cent of GDP by 2008, primarily reflecting large increases in the saving ratio and to a lesser extent the investment ratio in Asia, especially in China and India. However, the global saving and investment ratio is expected to fall back in 2009 in response to large declines � This article was prepared by Jennie Cassidy and David Orsmond of Economic Analysis Department, and extends the discussion in Orsmond D (2005), ‘Recent Trends in World Saving and Investment Patterns’, RBA Bulletin, October, pp 28–36. The data are primarily taken from the April 2009 World Economic Outlook database of the International Monetary Fund. The global saving and investment data shown in Graph 1 abstract from the large valuation changes in these data for the former Soviet Union in the period through 1991. More generally, country-specific saving and investment data are subject to significant measurement error, although the gap between the recorded global saving and investment ratios has been relatively small since the mid 1990s. B U L L E T I N | s e p t e m b e r� 2009 � � � ��� | A r t i c l e Graph 1 Global Saving and Investment Ratios Per cent of world GDP % % 24 24 23 23 Investment 22 22 21 21 Saving 20 1993 1997 2001 20 2009 2005 Source: IMF Graph 2 Saving Ratios – Selected Countries and Regions Per cent of GDP % Advanced Emerging 50 50 China Oil exporters 40 % Asia 40 Emerging Europe Japan 30 30 Euro area India 20 Latin America US 10 Rest of Asia 10 Anglo area 0 1993 2008 1993 2008 20 0 2008 1993 Sources: CEIC; IMF; RBA Graph 3 Investment Ratios – Selected Countries and Regions Per cent of GDP % Advanced Emerging 50 Rest of Asia 40 40 30 Euro area US 10 0 Anglo area 1993 Latin America R e s er v e b a n k India Japan 20 10 2008 1993 Sources: CEIC; IMF; RBA 50 China Emerging Oil exporters Europe 30 20 % Asia o f Au s tr a li a 2008 1993 0 2008 in these aggregates in the advanced economies in the context of the global recession. The global saving and investment ratio masks considerable diversity across countries and regions. Saving and investment ratios in Asia have historically been higher than those in all other regions, often by a considerable magnitude (Graphs 2 and 3). In addition, there is a large variation in the level of country saving and investment ratios within the Asian region – with the highest levels recorded in China and, more recently, India. In contrast, the saving and investment ratios of other advanced and emerging economies and regions have been broadly similar to each other through time, with the saving ratio of the oil exporters the only major exception. The pattern of net contributors to and absorbers of the pool of global saving has also been relatively similar over time. Saving ratios have generally exceeded investment ratios in Asia, and hence the region has run a current account surplus that has spanned many decades. This has been a notable feature of the Japanese economy since the 1980s, most other economies in east Asia after the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s, and China from the mid 2000s (Graph 4). Oil exporters (defined here as the Middle East region plus Russia) also became large suppliers of global saving in the 2000s following the sharp rise in the world price of oil. In contrast, in the United States, other English-speaking advanced countries (defined here as the ‘Anglo area’) and in Emerging Europe, the investment ratio has typically exceeded the saving ratio. Hence, these countries have tended to run persistent current account deficits and, as such, been net absorbers of global saving through time. The current account positions of the euro area and Latin America have fluctuated between deficits and surpluses. Graph 4 Current Account Balance – Selected Countries and Regions US$b Advanced Emerging US$b Asia China 400 400 Oil exporters Japan Euro area 0 Anglo Latin America area Emerging Europe India Rest of Asia 0 -400 -400 US However, while the pattern of -800 -800 1993 2008 1993 2008 1993 2008 net saving contributor and absorber Sources: CEIC; IMF; RBA countries and regions has been broadly similar through time, the absolute level of global current account balances has increased sharply over the past decade. Until the mid 1990s, deficits in the United States, the Anglo area and Latin America were primarily matched by surpluses in Japan. Between the late 1990s and the mid 2000s, the size of the US current account deficit doubled, with a corresponding increase in net saving in a range of countries in Asia, the Middle East, Latin America and the euro area. But since the mid 2000s the US current account deficit has been broadly flat. As such, the substantial rises in the current account surpluses in China and the oil exporters that have occurred since the mid 2000s have largely been matched by changes in the external positions of the euro area and Latin America – which switched from being net lenders to net borrowers over this period – and wider current account deficits in the Anglo and Emerging Europe areas. The rest of this article outlines the changes in the saving and investment ratios of the major countries and regions that have underpinned these developments. Developments in Saving and Investment Ratios outside Asia and the Oil Exporters As noted, the current account deficit in the United States widened sharply between the late 1990s and mid 2000s as the saving ratio fell – with a large decline in public saving in particular – while its investment ratio was boosted by a rise in housing construction (Graph 5). But since the mid 2000s, the US investment and saving ratios have changed by a broadly similar magnitude, and hence the US current account has been comparatively steady. Graph 5 United States % % Investment (per cent of GDP) 20 20 15 15 Saving (per cent of GDP) US$b 0 % Current account balance Level (LHS) 0 -400 -5 Per cent of GDP (RHS) -800 1983 1988 1993 1998 2003 -10 2008 Source: IMF B U L L E T I N | s e p t e m b e r� 2009 � � � ��� | A r t i c l e In the other advanced English-speaking countries, Australia has traditionally had among the highest national saving and investment ratios (Graph 6). Australia’s investment ratio has significantly exceeded its saving ratio through time, but since both ratios have tended to move together – rising noticeably Graph 6 since the early 1990s – Australia’s Anglo Area current account deficit as a share Per cent of GDP % of GDP has fluctuated around a Other Anglo area countries* % Australia relatively stable mean. In contrast, 28 28 while the average investment ratio Investment has also exceeded the saving ratio 24 24 in other Anglo countries, the size of the gap between these aggregates 20 20 has tended to trend in different directions over time. In the last few Saving 16 16 years, the average investment ratio of this group has increased while the 12 12 saving ratio has been broadly steady 1984 1996 2008 1984 1996 2008 * Unweighted average of Canada, NZ and UK and hence the group’s cumulative Sources: ABS; IMF; RBA; Thomson Reuters current account deficit has widened. Graph 7 Emerging Regions % Per cent of GDP Emerging Europe Latin America 28 % 28 Investment 24 24 20 20 Saving 16 12 16 1984 1996 2008 1984 Source: IMF 1996 12 2008 The average investment ratios in the Emerging Europe and Latin America regions have fluctuated over time, but both have increased in recent years (Graph 7). However, while the saving ratio has trended lower in Emerging Europe, it has increased markedly in Latin America. As a consequence, the size of the current account deficit has increased over time in the former region, but remained relatively contained in the latter. The euro area switched from being a net absorber of global saving during the 1980s and mid 1990s to being a net contributor for most of the period thereafter. But since the magnitude of the euro area’s saving and investment ratios has been similar through time, its current account position has remained fairly small. However, this masks very divergent trends across the countries of the euro area. In particular, the saving ratio in Germany has increased sharply since the mid 1990s and its investment ratio has fallen, while these ratios in other major countries of the euro area have moved in the opposite direction (Graph 8). The investment ratio in Spain in particular has boomed in the past decade, due in large part to the strength of R e s er v e b a n k o f Au s tr a li a housing construction, although this has started to unwind over the past few years. Developments in Saving and Investment Ratios in Asia and the Oil Exporters The Asian region has historically been a large supplier of global saving to the rest of the world. In Japan, while the saving ratio has persistently exceeded the investment ratio, both declined sharply during the economic slowdown in Japan in the 1990s (Graph 9). This downward trend stopped in the early 2000s, with the saving ratio rising somewhat while the investment ratio stabilised; as a consequence, the current account surplus increased somewhat for most of this decade. Other countries in Asia have also become significant suppliers of global saving during the past decade. After many years when the saving and investment ratios trended higher by a broadly similar magnitude, the average investment ratio in the rest of Asia region (Asia excluding Japan, China and India) fell sharply after the 1997–98 Asian financial crisis while its average saving ratio remained at a high level. As a consequence, this region has recorded a large current account surplus since that time (Graph 10). This trend is evident in both the newly industrialising economies of Asia (Hong Kong, Singapore, Korea and Taiwan) as well as the ASEAN group. Graph 8 Euro Area Per cent of GDP % Saving % Investment Spain 28 28 Germany 24 24 20 20 Italy 16 12 16 1984 1996 2008 1984 12 2008 1996 Sources: IMF; RBA; Thomson Reuters Graph 9 Japan % % 35 Saving (per cent of GDP) 30 30 25 25 Investment (per cent of GDP) US$b % Current account balance 200 10 Level (LHS) 100 0 -100 35 5 0 Per cent of GDP (RHS) 1983 1988 1993 1998 -5 2008 2003 Source: IMF Graph 10 Rest of Asia % % Saving (per cent of GDP) 30 30 25 25 Investment (per cent of GDP) US$b % Current account balance 100 5 0 -100 -200 Level (LHS) -5 Per cent of GDP (RHS) 1983 1988 1993 0 1998 2003 -10 2008 Sources: CEIC; IMF; RBA B U L L E T I N | s e p t e m b e r� 2009 � � � ��� | A r t i c l e Graph 11 China % % 55 55 Saving (per cent of GDP) 45 35 45 35 Investment (per cent of GDP) US$b % Current account balance 400 10 Per cent of GDP (RHS) 200 0 5 0 Level (LHS) -200 1983 1988 1993 1998 2003 -5 2008 Sources: CEIC; IMF; RBA Graph 12 India % % Investment (per cent of GDP) 30 20 30 20 Saving (per cent of GDP) US$b % Current account balance 100 5 Level (LHS) 0 0 Per cent of GDP (RHS) -100 -200 1983 1988 1993 1998 2003 -5 -10 2008 Sources: CEIC; IMF; RBA Graph 13 Oil Exporters* % % 45 45 Saving (per cent of GDP) 30 30 15 US$b 400 200 15 Investment (per cent of GDP) US$ 80 Crude oil (RHS, US$ per barrel) 40 0 0 Current account balance (LHS) -200 1983 1988 1993 1998 * Excludes Russia before 1992 Sources: IMF; RBA; Thomson Reuters R e s er v e b a n k o f Au s tr a li a 2003 -40 2008 China’s current account surplus remained very small for an extended period, as China’s saving and investment ratios were broadly equal. However, starting from the early 2000s, China’s saving ratio increased especially rapidly, driven in particular by a large increase in saving by the corporate sector. While the investment ratio also increased during this period, the rise was smaller (Graph 11). As a consequence, China has become one of the largest suppliers of global saving – totalling around $440 billion in 2008 – with a current account surplus of over 10 per cent of GDP in 2008, compared with around 3 per cent as recently as 2004. Like China, the saving ratio in India also increased sharply during the 2000s, rising from around one-quarter of its GDP in 2001 to be well over one-third by 2008, driven by increases in saving by the household, corporate and government sectors (Graph 12). However, unlike China, the surge in India’s saving ratio has continued to be matched by a commensurate increase in its investment ratio. As a consequence, India has recorded only very modest current account positions through time. Finally, the average saving ratio of the oil exporters (the Middle East region plus Russia) has fluctuated widely in line with changes in world oil prices, with the saving ratio having risen sharply in the 2000s (Graph 13). In contrast, their investment ratio has remained fairly steady through time, at around the levels seen in other regions outside of Asia. As a consequence, the combined current account surplus of the oil exporters increased sharply in recent years, standing at over $440 billion in 2008. Trends in 2009 The recent sharp downturn in global economic activity is projected to lead to a significant fall in the global saving and investment ratio and large shifts in the current account positions of some major countries and regions. Most of this reflects the sharp fall in the investment ratio in the United States in 2009 – driven by a slump in domestic demand and tight financial conditions – as well as sharply reduced saving in the oil exporters following the large fall in oil prices since mid 2008 (Graph 14). The current account of the oil exporters is expected to be in broad balance in 2009. Graph 14 Current Account Balances US$b US$b ■ 2008 ■ 2009 (estimate) 300 300 0 0 Oil exporters Anglo area China -900 Japan -900 Rest of Asia -600 Latin America -600 Euro area -300 Emerging Europe -300 US In comparison, the projected changes in current account positions in other economies and regions in 2009 are fairly small. Like in the United States, the investment ratio in Emerging Europe is expected to decline, with an accompanying reduction in the size of the region’s current account deficit. While the investment ratio in Japan is also projected to fall, its saving ratio is expected to decline somewhat faster. In contrast, the investment and saving ratios and the size of the current account surplus in China are expected to remain very high in 2009. R Source: IMF B U L L E T I N | s e p t e m b e r� 2009 � � � ��� | A r t i c l e