Box C: Margin Lending

advertisement

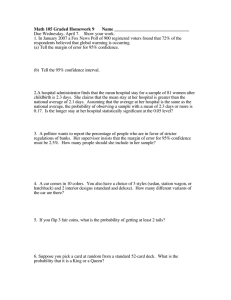

Reserve Bank of Australia Bulletin May 2000 Box C: Margin Lending In recent years household borrowing to finance investment in the share market has increased. Some of this has been through personal loans and loans secured against houses and, therefore, the amount of such activity is not easily measurable. Some of the lending, however, has been more direct, taking the form of ‘margin lending’. Margin loans involve the borrower lodging cash or shares with the lender (typically a bank or stockbroker), which then supplements the investor’s capital by providing a line of credit. This line of credit – the margin loan – plus the borrower’s own capital are used to purchase shares, which then become the security for the loan. Margin loans have been available in Australia since the late 1970s, although they have increased strongly in recent years as most retail banks and larger stockbrokers now offer this product. Margin loans outstanding from banks and brokers rose from $2 billion in September 1996, when the Reserve Bank began informally collecting this information, to $6.3 billion in the March quarter of 2000. Over the past year, margin lending has increased by 50 per cent, although there are some signs that this growth might have begun to slow following the absorption of the Telstra 2 sale. Interest rates on margin loans are currently around 8.4 per cent, about 0.7 of a percentage point higher than for a residentially-secured line of credit, but almost 2 percentage points below the interest rates available on other secured personal loans. Fast growth in margin lending over recent years mirror s developments overseas. For example, over the year to March 2000, margin lending in the US grew by 78 per cent. While the recent rate of growth of margin lending in Australia has been high, the level of margin debt remains relatively low. The value of outstanding margin loans represents about 0.9 per cent of market capitalisation of the Australian Stock Exchange, around 1 per cent of GDP and 1.3 per cent of the household sector’s gross liabilities. These figures are well below those for the US (Graph C1). The level of margin loans is not thought to pose any significant prudential risk to the individual lenders involved, or systemic risk for the financial system as a whole, given that they account for such a small part of total lending. Whether margin loans will adversely affect the share market in the event of a market correction is, however, less clear. Graph C1 Margin Debt Outstanding As at December 1999 % 3.0 2.5 % 3.0 Australia United States 2.5 2.0 2.0 1.5 1.5 1.0 1.0 0.5 0.5 0.0 As a per cent of market capitalisation As a per cent of GDP As a per cent of household liabilities 0.0 Leverage and risk By leveraging their own capital with a margin loan, it is possible for investors to control a much larger portfolio than they could if they were to invest only their own capital. Leverage, however, magnifies both the potential gains and losses that might result from fluctuations in equity prices (see example below). Financial institutions typically designate the range of securities which they are prepared to accept as collateral in order to limit their potential exposure to investors 29 Semi-Annual Statement on Monetary Policy with margin loans. In Australia, lenders also typically limit the funding from margin loans to a maximum of 70 per cent of a portfolio of ‘blue-chip’ stocks; a larger equity contribution would be required of investors buying other securities. Larger margin lenders in Australia say that Australian borrowers typically gear their portfolios conservatively, providing around 50 per cent of funds from their own resources. This operates to minimise investors’ exposure to market volatility, particularly the risk of receiving a margin call. Banks and brokers make margin calls when falling share prices result in the Example: The effects of leverage Initial portfolio value: $100 000 Investor’s equity contribution: $30 000 Margin loan: $70 000 Maximum gearing ratio prescribed by the lender: 70 per cent Case 1: Market value of portfolio rises by 10 per cent New portfolio value: $110 000 Gearing ratio: 63.6 per cent ($70 000/ $110 000) Return on investor’s equity: 33.3 per cent ($10 000/$30 000) In the absence of the margin loan, the investor’s return would have been 10 per cent, the same as the rise in the market value of the portfolio. To the extent that the investor still has unused margin credit available, the investor could purchase up to about an additional $23 000 of shares, to restore the gearing ratio to 70 per cent. This would tend to reinforce buying pressure in the market. 30 May 2000 market value of a borrower’s equity falling below the minimum level prescribed by the lender (see Case 2 in example). When a margin call is made, borrowers must restore, within 24 hours, their gearing to the ratio required by the lender. Borrowers can provide additional equity (in the form of cash or approved securities) or instruct their lender to sell some shares from the portfolio and use the proceeds to repay part of the debt. If they fail to take either of these courses of action, the lender has the power to sell sufficient securities to restore the required ratio. R Case 2: Market value of portfolio falls by 10 per cent New portfolio value: $90 000 Gearing ratio: 77.8 per cent ($70 000/ $90 000) Return on investor’s equity: –33.3 per cent With the gearing ratio exceeding the prescribed maximum, a margin call is triggered, with the investor required to restore the gearing ratio to 70 per cent. The investor could do this in one of three ways: • Paying a minimum of $7 000 in cash, thereby reducing the loan to $63 000. • Providing the equivalent of at least $10 000 extra in approved securities, restoring the portfolio to its initial value of $100 000, with a loan of $70 000. • Selling about $23 000 in shares out of the leveraged portfolio, and using the proceeds to repay the debt. This would leave the investor with a portfolio valued at about $67 000, a loan of $47 000 and investor’s equity of $20 000. This sale of shares is larger than the margin call in cash or securities because, as the investor’s equity has been reduced to $20 000 by the decline in the market value of the portfolio, the maximum loan size this will support is about $47 000. Therefore, if the investor was not willing to top up the equity in the portfolio, the investor would have to sell enough shares (i.e. about $23 000) to raise cash to reduce the loan to this level.