Standard 5: Technical Quality

advertisement

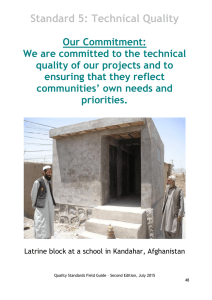

Standard 5: Technical Quality Our Commitment: We are committed to the technical quality of our projects and to ensuring that they reflect communities’ own relief and recovery priorities. Latrine block at a school in Kandahar, Afghanistan Quality Standards Field Guide – First Edition, December 2009 Standard 5: Technical Quality The issues Project evaluations in the past have criticised NGOs for carrying out projects which are of poor technical quality – for example a building which was poorly designed or used inappropriate materials or a feeding programme which didn’t follow agreed nutrition standards. The project staff may have been well meaning but they didn’t have access to technical support or qualified professionals who could ensure the project’s design was technically appropriate. The Tsunami Evaluation Coalition in its evaluation of the tsunami response noted the poor technical quality of some projects and identified one of the contributing factors as being the lack of suitably skilled staff and another as being the extension by some NGOs into sectors that they had no previous experience or competence in. This came alongside another criticism: that the projects carried out did not actually reflect the priorities of the communities themselves. The TEC recommended that NGOs “concentrate their efforts, and develop deeper competence in specific sectors”. There is also growing recognition of the differences between demand-led and supply-driven approaches. Demand-led approaches are processes that empower beneficiaries to address the needs that they perceive as important. This builds on the comment above about projects needing to reflect the priorities of the communities themselves. Supply driven approaches by contrast focus on providing assistance, which requires input from the community or beneficiary but the project is based on the supply of materials and approaches as opposed to demand from the community. More recently we are recognising the superiority of demand-led approaches, such as Community-Led Total Sanitation (CLTS). Projects are sometimes described as having “hardware” and “software” components: “hardware” meaning the physical or constructed provisions of a project, such as a well, a latrine or a school building, and “software” meaning the ownership, knowledge, understanding and skills which are needed if such physical provisions are to be properly owned and have lasting impact. NGOs need to have both the technical skills to provide the “hardware” requirements of the project and the sociological skills for engaging with communities and so provide the “software” requirements. Biblical foundations The book of Nehemiah provides a good example of technical quality considerations, when the prophet sets about rebuilding the walls of Jerusalem. In ancient times, most cities had city walls. The wall was an important defence that surrounded the city. It would be strong and high and several metres thick. The wall that Nehemiah planned to rebuild needed to be of sufficient quality if it was to be a defence. Quality Standards Field Guide – First Edition, December 2009 Standard 5: Technical Quality Good Practice commitments Tearfund’s commitment is to ensure that emergency projects are of good technical quality, and that they reflect communities’ own relief and recovery priorities. When considering technical quality, the issues of sustainability and replicability need to be assessed; for example it may be possible in theory to design and build a latrine which is a very high technical quality, but it isn’t sustainable if the owner can’t replace it in the future and it isn’t replicable if others in the community can’t afford to build to the same design. Standards of technical quality therefore need to be assessed for the context and the issues of supply and demand need to be carefully considered. The Sphere handbook (see introduction on page 143) provides technical guidance for a wide range of sectors and should be used to help guide assessment, project design and implementation. Assessment checklists are provided and are a good reference to help you decide what technical questions to ask in an assessment, and the Sphere standards and indicators can be used in the project logframe. Close links to other Quality Standards There are close links with Disaster Risk, as we need to address underlying vulnerabilities in our technical design (e.g. earthquake resilient buildings); Children and Gender, as we need to ensure that technical design is appropriate for the needs of boys and girls, women and men; Environment, with the need to consider impact on the environment in our technical design; and Sustainability, as projects need to be locally sustainable and responsive to demand as well as being of good technical quality. Where to look for further information: • • • • • • • • • • • • The Sphere Handbook (see introduction on page 143) Nutrition: Valid International Community Based Therapeutic Care Food Security: LEGS (FAO Website) WASH: http://www.communityledtotalsanitation.org/page/about-site http://www.redr.org/redr/support/resources/EinE/EinE.htm http://www.actionagainsthunger.org/resources/water-sanitation-hygienepopulations-risk http://wedc.lboro.ac.uk/WHO_Technical_Notes_for_Emergencies/ http://tilz.tearfund.org/webdocs/Tilz/Topics/Why%20advocate%20for%20w ater,%20sanitation%20and%20hygiene.pdf http://tilz.tearfund.org/Topics/Water+and+Sanitation/Water+Safety+Plans .htm Shelter and Construction: Lessons from Aceh: Key Considerations in PostDisaster Reconstruction (by Jo da Silva - Disasters Emergency Committee / ARUP / Practical Action Publishing) Education: Inter-Agency Network for Education in Emergencies Health Promotion: Tearfund Children’s Health Promotion Manual Quality Standards Field Guide – First Edition, December 2009 Standard 5: Technical Quality Practical Steps for carrying out our Technical Quality commitment Identification Step 1: Be clear on your own areas of specialism and technical strengths as an organisation Step 2: Understand the priorities expressed by the community, and identify which areas you have the technical experience and capacity to support Design Step 3: Ensure your project staff have the technical support needed to guide project implementation Implementation Step 4: Ensure quality control when you are working with contractors Step 5: Monitor and evaluate the project and make technical adjustments where necessary Quality Standards Field Guide – First Edition, December 2009 Standard 5: Technical Quality Step 1: Be clear on your own areas of specialism and technical strengths as an organisation Is there a clear understanding amongst staff of the specialisms of your organisation – what types of projects you do and don’t carry out? Avoid the danger of trying to meet needs in a situation where you do not have the necessary technical experience. Also avoid the temptation of designing your project based on what donors are wanting to fund, when these don’t fit with your areas of specialism. Step 2: Understand the priorities expressed by the community, and identify which areas you have the technical experience and capacity to support When you carry out assessments, ensure that you gather detailed information that relates to your areas of specialism e.g. water and sanitation, food, shelter. The assessment checklists in the Sphere handbook can be helpful in deciding what technical questions to ask. As the community shares priority needs in areas which are outside of your areas of specialism, you have an important role to play in advocating to others to respond to these needs. Quality Standards Field Guide – First Edition, December 2009 Standard 5: Technical Quality Step 3: Ensure your project staff have the technical support needed to guide project implementation For any project that needs technical input, make sure that this input is available to the project staff responsible for the project, both for its design and for implementation. This could be arranged through the hiring of suitably qualified and experienced staff (e.g. nutritionists, engineers, nurses) or drawing on the support of technical advisors or consultants. Such advisors can provide helpful comments even just by reading through the project proposal. Remember that both the “hardware” and “software” requirements of the project need to be adequately supported and the level of demand carefully considered. Step 4: Ensure quality control when you are working with contractors Some projects may involve subcontracting, often ones that involve large scale construction e.g. building homes or schools. In these situations the construction company rather than the NGO carries out the actual building work and good quality control is needed so that you can be sure that the work carried out by the company is of high technical quality. In these project situations, it is important to appoint a supervisor to oversee the work, checking for example that concrete is made to the correct ratios, foundations are properly laid, building design is closely followed, and so on. Depending on the situation and the reliability of the contractor, such monitoring may need to be daily. Quality Standards Field Guide – First Edition, December 2009 Standard 5: Technical Quality Step 5: Monitor and evaluate the project and make technical adjustments where necessary This involves monitoring and capturing learning to ensure technical standards are being maintained, but also checking to confirm that the project still meets communities’ own priorities and there is good acceptance. It also involves considering the issues of sustainability and replicability as set out in the Practical Steps listed under Sustainability. Monitoring technical quality which stems from a social marketing or demand-led approach brings challenges in ensuring the approach is demand-led and based on community and individual action, whilst also ensuring appropriate minimum technical design and structural safety. Quality Standards Field Guide – First Edition, December 2009 Standard 5: Technical Quality Project Examples A partner working in the Andaman Islands after the tsunami, realised that there was greater technical expertise available in the area of training and supporting livelihoods by liaising with local government departments than they would be able to provide internally. Therefore they established a relationship and linked in their beneficiaries with government schemes. This was also more sustainable. A post-tsunami housing project in Indonesia using contractors resulted in houses that were of poor quality. The decision was made to put in some more funds for remedial work, but this time to enable the home-owners to do the necessary improvements. Cluster groups were set up in each village, the members were trained in each of the issues in the key stages in house improvement, then they were given a grant for one stage of work, the quality of that work was checked by partner staff engineers, with the cluster receiving their next grant instalment only when all their members had completed the renovations to a satisfactory standard. By the end of the remedial work, the community were reporting that they were satisfied with the quality of their homes mainly because they had been enabled to do the work for themselves. Quality Standards Field Guide – First Edition, December 2009