Standard 5: Technical Quality

advertisement

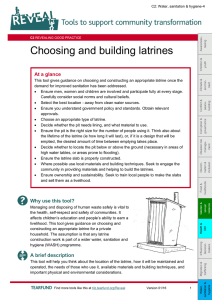

Standard 5: Technical Quality Our Commitment: We are committed to the technical quality of our projects and to ensuring that they reflect communities’ own needs and priorities. Latrine block at a school in Kandahar, Afghanistan Quality Standards Field Guide – Second Edition, July 2015 48 Standard 5: Technical Quality The issues Project evaluations in the past have criticised NGOs for carrying out projects which were of poor technical quality – for example a building which was poorly designed or which used inappropriate materials, or a feeding programme which didn’t follow agreed nutrition standards. The project staff had good intentions but they did not have access to the right technical support or qualified professionals. Such criticisms have applied in both relief and development. After the 2004 tsunami, an evaluation of the response noted the poor technical quality of some projects. One reason for this was the lack of suitably skilled staff and another was the extension by some NGOs into sectors in which they had no previous experience or competence. This came alongside another criticism: that the projects carried out did not actually reflect the priorities of the communities themselves. The evaluators recommended that NGOs “concentrate their efforts, and develop deeper competence in specific sectors”. There is also growing recognition of the differences between demand-led and supply-driven approaches when working with a community. Demand-led approaches use processes that empower beneficiaries to address the needs that they perceive as important. This builds on the comment above about projects needing to reflect the priorities of the communities themselves. Supply driven approaches, by contrast, focus on providing assistance, which may require a little input from the community (or beneficiary) but the project is based on the supply of materials and services, not upon the priority needs expressed by the community. More recently we have been recognising the superiority of demandled approaches, such as Community-Led Total Sanitation (CLTS). Projects are sometimes described as having “hardware” and “software” components. “Hardware” means the constructions or physical inputs of a project, such as a well, a latrine or a school building. “Software” means the ownership, knowledge, organisation and skills that are needed if the physical provisions are to be properly used and have lasting impact. NGOs need to have both the technical skills to provide the “hardware” requirements of the project and the sociological skills for engaging with communities to provide the “software” requirements. Biblical foundations The book of Nehemiah provides a good example of technical quality, when the prophet sets about rebuilding the walls of Jerusalem. In ancient times, most cities had a perimeter wall. The wall was an important defence that surrounded the city. It would be strong and high and several metres thick. The wall that Nehemiah planned to rebuild needed to be of sufficient quality if it was to be a Quality Standards Field Guide – Second Edition, July 2015 49 Standard 5: Technical Quality defence. He persisted with the project, despite the unjustified criticism and mocking from his enemies (Neh.4: 1-9). Good Practice commitments Tearfund’s commitment is to ensure that all projects are of good technical quality, and that they reflect communities’ felt needs and priorities. Technical quality relates to sustainability and replicability. For example, it may be possible to design and build a latrine that is of very high technical quality. However, the benefits are not sustainable if the owner can’t maintain it and other people are unable to afford to replicate this design. Standards of technical quality should therefore be influenced by the context; good or appropriate quality is not the same as best quality. Every project type will have its own relevant technical standards. If it involves construction, building codes must be met. If it involves education, then issues of national curriculum content and standards of teacher training will be important. Other technical areas of current focus for Tearfund include WASH (Water, Sanitation and Hygiene), Food Security, Livelihoods, prevention of Sexual Violence, Cash Programming, Peace Building, Resilience and specifically within Disaster Management: Shelter, Protection, Nutrition and Psychosocial Support. Appropriate technical support and quality are needed in each of these areas. The Sphere handbook (see introduction on page 154) provides core standards for all project types, plus technical guidance for work in a wide range of sectors. These standards can be used to guide our assessments, inform project design and assist our implementation. Assessment checklists are provided and are a good reference to help design more technical questions. The Sphere standards and indicators can also be used in the project log frame. Close links to other Quality Standards Our commitment to Technical Quality has close links with: Disaster Risk, as technical quality needs to be sufficiently robust to address underlying vulnerabilities (e.g. earthquake resilient buildings); Children and Gender, as technical design must be appropriate for the needs of boys and girls, women and men, and all should have the opportunity to influence the quality of the inputs; Accountability, in that there should be community participation in decision making & opportunity to complain if quality is poor; Environment, in that the technical design should not impact heavily upon the environment; Sustainability, as projects need to be locally sustainable and responsive to demand as well as being of good technical quality. Quality Standards Field Guide – Second Edition, July 2015 50 Standard 5: Technical Quality Where to look for further information: The Sphere Handbook (see introduction on page 154) Nutrition: Valid International Community Care: http://www.validinternational.org/about-us/ Food Security (Livestock): Livestock Emergency Guidelines (LEGS) Cash Programming: CALP http://www.cashlearning.org WASH: Community Led Total Sanitation: http://www.communityledtotalsanitation.org/page/about-site REDR UK Emergency Preparedness resources: http://www.redr.org.uk/en/resources/index.cfm/emergencypreparedness WHO Technical Notes for Emergencies: http://wedc.lboro.ac.uk/knowledge/notes_emergencies.html Shelter and Construction: Lessons from Aceh: Key Considerations in PostDisaster Reconstruction (by Jo da Silva - Disasters Emergency Committee / ARUP / Practical Action Publishing): http://www.dec.org.uk/sites/default/files/pdf/lessons-from-aceh.pdf Education: Inter-Agency Network for Education in Emergencies: http://www.ineesite.org/en/ Quality Standards Field Guide – Second Edition, July 2015 51 Standard 5: Technical Quality Practical Steps for carrying out our Technical Quality commitment Identification Step 1: Be clear on your own areas of specialism and technical strengths as an organisation, and those of your partners Step 2: Understand the priorities expressed by the community, and identify which areas you have the technical experience and capacity to support Design Step 3: Ensure your project staff have the technical support needed to guide project implementation Implementation Step 4: Ensure quality control when you are working with contractors, and when supervising construction Step 5: Monitor and evaluate the project and make technical adjustments where necessary work directly. Quality Standards Field Guide – Second Edition, July 2015 52 Standard 5: Technical Quality Step 1: Be clear on your own areas of specialism and technical strengths as an organisation, and those of your partners Is there a clear understanding amongst staff of the specialist knowledge and experience of your organisation? What are the types or sectors of project which you do and don’t carry out? Avoid the danger of trying to meet needs in a situation where you do not have the necessary technical experience. Also avoid the temptation of designing your project based on what donors want to fund, when these don’t fit with your areas of specialism. Step 2: Understand the priorities expressed by the community, and identify which areas you have the technical experience and capacity to support When you carry out assessments, ensure that you gather detailed information that relates to your areas of specialism e.g. water and sanitation, or food distribution, or shelter. The assessment checklists in the Sphere handbook can be helpful in deciding what technical questions to ask. If the community shares priority needs in sectors which are outside of your areas of specialism, then you should seek to link the community with other agencies or Government Departments, who do have the skills to respond to these needs. Quality Standards Field Guide – Second Edition, July 2015 53 Standard 5: Technical Quality Step 3: Ensure your project staff have the technical support needed to guide project implementation For any project that needs technical input, make sure that this input is available to the staff responsible for the project, both for its design and later for implementation. This could be arranged through the hiring of suitably qualified and experienced staff (e.g. nutritionists, engineers, nurses) or drawing on the support of technical advisors or consultants. Such advisors can provide helpful comments, perhaps just by reading through the project proposal. Remember that both the “hardware” (inputs) and “software” (knowledge/skills/organisation) requirements of the project need to be adequately supported and the level of demand carefully considered. Quality Standards Field Guide – Second Edition, July 2015 54 Standard 5: Technical Quality Step 4: Ensure quality control when you are working with contractors, and when supervising construction work directly. Some projects may involve sub-contracting. For example, large scale construction projects e.g. building homes, clinics or schools. In these situations the construction company rather than the NGO carries out the actual building work and good quality control is needed so that you can be sure that the work carried out by the company is of high technical quality. In these project situations, it is important to appoint a supervisor to oversee the work, checking for example that concrete is made to the correct ratios, foundations are properly laid, building design is closely followed, and so on. Depending on the situation and the reliability of the contractor, such monitoring may take place daily. Step 5: Monitor and evaluate the project and make technical adjustments where necessary This involves monitoring to ensure technical standards are being maintained, capturing learning for future projects and also checking to confirm that the project still meets communities’ own priorities. If this is the case, then there will be good acceptance. Negative feedback on quality should be carefully considered and acted upon, with a response given to those making complaints. Quality Standards Field Guide – Second Edition, July 2015 55 Standard 5: Technical Quality Project Examples A partner working in the Andaman Islands after the tsunami realised that there was greater technical expertise available in the area of training and supporting livelihoods by liaising with local government departments than they would be able to provide internally. Therefore they established a relationship and linked in their beneficiaries with government schemes. This was also more sustainable. A post-tsunami housing project in Indonesia using contractors resulted in houses that were of poor quality. The decision was made to put in some more funds for remedial work, but this time to enable the homeowners to do the necessary improvements themselves. Cluster groups were set up in each village, the members were trained in each of the issues in the key stages in house improvement, then they were given a grant for one stage of work, the quality of that work was checked by partner staff engineers, with the cluster receiving their next grant instalment only when all their members had completed the renovations to a satisfactory standard. By the end of the remedial work, the community were reporting that they were satisfied with the quality of their homes mainly because they had been enabled to do the work for themselves. In Uganda, a partner was implementing water and sanitation projects but there was demand from the community for the construction of rainwater harvesting structures at household and community level. To ensure technical quality, the partner established contact with another partner in southern Uganda who was very experienced in this area. The partner provided them, and the local community, with training in the construction of rainwater harvesting structures, with follow up support and facilitated exchange visits. This meant the project was of higher technical quality and the partner staff and community learnt new skills. Quality Standards Field Guide – Second Edition, July 2015 56