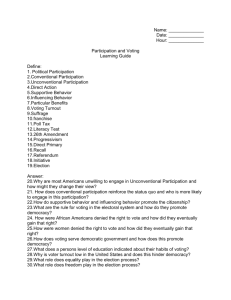

CALTECH/MIT VOTING TECHNOLOGY PROJECT

advertisement