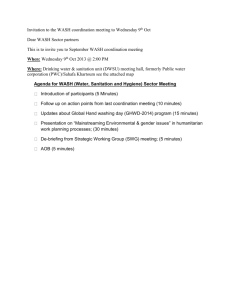

Relationships between water supply, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) service delivery and

advertisement