Transport Needs Analysis for Getting There and Back:

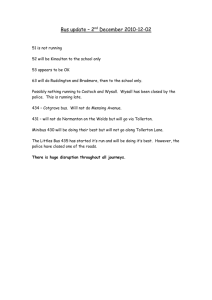

advertisement