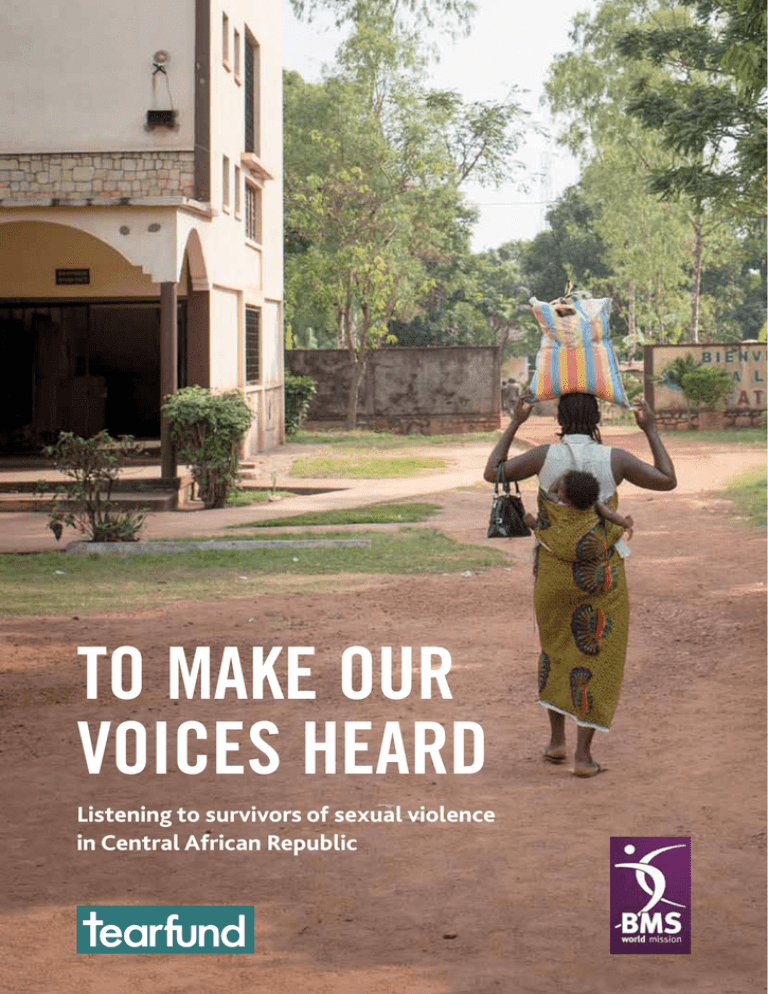

To Make our Voices Heard Listening to survivors of sexual violence

advertisement