K [ 1 1 I

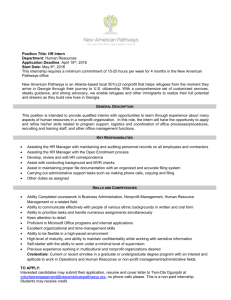

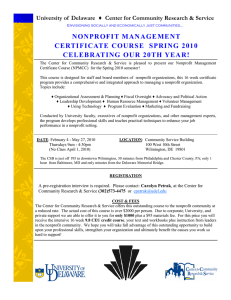

advertisement