Between Control and Support. The Protection Risk: The Dutch Case

advertisement

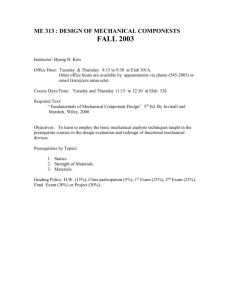

doi: 10.1111/imig.12178 Between Control and Support. The Protection of Unaccompanied Minor Asylum Seekers at Risk: The Dutch Case Moira Galloway*, Monika Smit* and Mariska Kromhout** ABSTRACT Drawing on research by the Research and Documentation Centre (WODC) of the Dutch Ministry of Security and Justice (Kromhout et al., 2010), this article describes how the Dutch government tried to protect Unaccompanied Minor Asylum Seekers (UMAs) who were (at risk of becoming) victims of human trafficking by implementing “Protected Reception”. It was concluded that the three objectives of this pilot programme were met to some extent: the influx of risk groups and the number of disappearances decreased, yet there was no (immediate) increase in return migration to the country of origin, after leaving Protected Reception. An important question that was raised was how far a state can go in protecting these vulnerable young people, by (partially) limiting their freedom of movement. It was concluded that placement and stay in Protected Reception had to be qualified as a deprivation of liberty for which Dutch legislation did not offer any ground. INTRODUCTION Many countries around the world are facing an influx of Unaccompanied Minor Asylum seekers (UMAs). In a number of member states of the European Union (EU), disturbing numbers of UMAs have gone missing in recent years (Delbos, 2010; European Migration Network (EMN), 2010; European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2011; Hancilova and Knauder, 2011; Pearse, 2011). Possible causes are that UMAs are disappointed by the protection system in the (initial) country of destination; they may fear a negative asylum decision or detention; or they see the reception centre as a transfer point en route to an intended country of destination (Hedjam, 2009; Hancilova and Knauder, 2011), possibly to be reunited with relatives. However, these disappearances may also be related to the fact that some UMAs are destined for exploitation, and might thus become victims of human trafficking (Van den Borne and Kloosterboer, 2005; Boermans, 2009; Kromhout, Liefaard, Galloway, Beenakkers, Kamstra, and Aidala, 2010). Many EU member states took specific measures to protect UMAs who were identified as victims of trafficking (EMN, 2010). In the Netherlands, the protection of UMAs was placed high on the political agenda when, between the autumn of 2004 and the autumn of 2005, 125 Indian UMAs disappeared from the reception centres for UMAS, followed by the disappearance of approximately 140 Nigerian UMAs between 2006 and 2007. In response, the level of security was increased on UMA-campuses and a large-scale criminal investigation was started (named “Koolvis”). In December 2006, the then * Ministry of Security and Justice, The Hague. ** Netherlands Institute for Social Research, The Hague. Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd. © 2014 The Authors International Migration © 2014 IOM International Migration Vol. 53 (4) 2015 ISSN 0020-7985 52 Galloway, Smit and Kromhout Minister of Immigration Affairs and Integration proposed to Parliament a two-year pilot programme named “Protected Reception”, for UMAs between the age of 13 and 18. The target group consisted of UMAs who, according to the experience of the Immigration Service, were at risk of disappearing. The Protected Reception programme started on 1 January 2008, with a capacity for 45 UMAs, in five locations in the north and the south of the Netherlands (Kromhout et al., 2010). There is an extensive body of literature on UMAs in general (Chase, 2010), but relatively little is known about UMAs who are (at risk of becoming) victims of human trafficking (hereafter: “UMAs at risk”) (Derluyn, Lippens, Verachtert, Bruggeman, and Broekart, 2009), or about the protection measures available for this group. This article describes how the Dutch government protected this specific category of UMAs through Protected Reception. Through this kind of reception, the Dutch government aimed 1) to reduce the number of disappearances; 2) to reduce the influx of UMAs at risk, and 3) to increase the number of minors who return to their country of origin. This article addresses the questions: To what extent have these objectives been realized in practice; what difficulties are involved in this specific form of reception to protect vulnerable UMAs; and how did Protected Reception develop after the pilot? PROTECTED RECEPTION: POLICY THEORY AND SELECTION Policy theory and expected efficacy Various measures were implemented to achieve the objectives described above. In comparison to regular reception, the level of security was increased in Protected Reception, and the UMAs were placed under intensive supervision. The presumed mechanisms were not made explicit in the relevant policy documents, but seem to have been the following: 1 The implemented protection measures form a physical boundary against disappearing from the reception centre. As a result fewer UMAs will go missing. 2 The implemented protection measures make it impossible for UMAs to contact their traffickers, which will make it easier for them to detach psychologically from their traffickers which will decrease the number of disappearances. 3 By making UMAs aware of the exploitative situation that possibly awaits them, and by offering them an alternative (filing a complaint or returning to the country of origin), UMAs no longer wish to be in contact with their traffickers. This will decrease the number of disappearances and increase the number of (potential) victims who file a complaint or return to the country of origin. Moreover, better criminal investigations are possible with increased numbers of traffickers being prosecuted. 4 Since traffickers ‘lose’ their victims as soon as they are placed in Protected Reception, and because the incriminating statements of these (potential) victims increase the chance of their traffickers being identified and prosecuted, they will no longer bring their victims to the Netherlands. Selection procedure UMAs enter Protected Reception via the Application Centre at Schiphol Airport in Amsterdam, the capital of the Netherlands. They arrive at Schiphol through different paths. “Air-UMAs” arrive by plane and directly report themselves or are stopped at the border due to the lack of necessary or valid documents. “Land-UMAs” report themselves at Schiphol airport, in a central reception location or are located by police somewhere in the Netherlands, and are then brought to the Application Centre at Schiphol. © 2014 The Authors. International Migration © 2014 IOM The Protection of Unaccompanied Minor Asylum Seekers at Risk 53 The selection for Protected Reception differs slightly according to age group. Older UMAs (from 15 to 18) have an intake at the aliens police,1 who take photographs and fingerprints and conduct a first interview. Next, the UMAs receive information from the Council for Refugees followed by an interview with the Immigration Service during which they are asked about their nationality and identity. After this interview, the minors have an intake with Nidos, the Dutch guardianship and family supervision foundation that carries out the guardianship task for UMAs.2 During the intake the UMAs are questioned about travel companions, who financed the journey, certain events during the voyage and after arrival in the Netherlands, and possible arrangements with a travel agent. This takes place within 24 hours after arrival at Schiphol. Additionally, the Health Service inquires about the minors’ health and offers medical assistance when needed. A second interview with the Immigration Service either takes place at the Application Centre or at a local Immigration Service office. When a minor decides to press charges, or the Immigration Service spots indicators of human trafficking, the Military Policy conducts an interview. The most significant difference with younger UMAs (13 or 14 years old) is that they are placed in a foster home by Nidos after their interview with the aliens police and before their first interview with the Immigration Service. Nidos has the final say in who enters Protected Reception. Generally this decision is made between the first and the second interview with the Immigration Service and based on possible advice provided by other organizations. Different methods are used to identify (potential) victims of human trafficking. First, confidential “risk-profiles” of the Immigration Service may be consulted. These present an overview of characteristics for specific nationalities that are considered to be at greater risk of falling victim to human trafficking. Second, a list with signals from the Procurators-General’s office is used to spot (potential) minor victims; and third, “gut feelings” or “a feeling that something is not right” are involved. Both verbal and non-verbal reactions from the UMAs are taken into account. RESEARCH METHODS This article is based on an evaluation study conducted by the Research and Documentation Centre of the Dutch Ministry of Security and Justice (Kromhout et al., 2010)3 and on information from Nidos and the Central Agency for the reception of asylum seekers about the situation, following the completion of the pilot. Several research methods were used, both qualitative and quantitative. In the period November 2009 to April 2010, semi-structured interviews were held with staff members – both managers and executive officers – of the different Protected Reception locations, various other executive organizations that were involved in the pilot, and UMA lawyers. Additionally, information was gathered through face-to-face interviews, by phone or by e-mail, from several non-pilot social service organizations specialized in human trafficking and/or in UMAs. All interviews were recorded, transcribed and thematically analysed. No UMAs were interviewed. This was decided in consultation with Nidos, to avoid further burdening these often traumatized young people. As a result, the perceptions of UMAs at risk were gathered from a secondary source. Nidos guardians were asked to analyse the client file of every UMA who had entered Protected Reception on or after 1 January 2009 (the starting date of the pilot), using a structured code sheet. These files hold information about the asylum procedure, plans and evaluations regarding the guidance of the UMA and reports of conversations with the UMA. Forty-nine client files of 17 boys and 32 girls of 18 different nationalities were used in our final analysis.4 For insight into the protection measures at the different Protected Reception centres, we also visited the actual locations. Additionally, UMA trend reports and risk profile reports by the Immigration Service were studied. These include information about indicators of human trafficking, remarkable characteristics of the UMAs at risk, their trafficking routes and their disappearances. © 2014 The Authors. International Migration © 2014 IOM 54 Galloway, Smit and Kromhout Quantitative data were obtained from various organizations (the Dutch Ministry of Security and Justice, the Immigration Service, the Central Agency for the reception of Asylum Seekers, the Repatriation and Departure Service and the International Organization for Migration, IOM). This data pertained to (among other things) the background of the UMAs in Protected Reception (August 2006 - December 2009), the asylum inflow to and outflow from the Netherlands, and the number of UMAs returning to their countries of origin. These data were not always complete (e.g. the registration by the Immigration Service of asylum and applications within the Residency Regulation Human Trafficking). Finally, from February through April 2010, Liefaard (2010) performed a legal study, based on an analysis of the national and international laws on freedom deprivation and restriction, and concerning relevant laws and regulations, scientific literature and relevant judgements. RESULTS Protected Reception in practice Population The Protected Reception centres in the north of the Netherlands were divided into locations for boys and locations for girls. In the south only girls were accommodated. There were first and second phase locations, with the first phase being more secured and with a relatively high level of supervision compared with second phase locations, where UMAs were given more freedom of movement. UMAs generally stayed three months in the first phase and up to six months in the second phase. Between 1 January 2008 and 31 December 2009, a total of 170 UMAs entered one of the five Protected Reception locations.5 One third were boys, two thirds were girls, and the largest age group (over 80%) was between 15 and 17 years old. The origin of UMAs in Protected Reception varied greatly. In 2008 and 2009 the majority were Guinean (24%), Chinese (13%), Nigerian (12%) or Indian (10%). After 2008, the number of Indian and Chinese UMAs decreased significantly, and the variety of nationalities increased. Most UMAs who entered Protected Reception applied for asylum, with a small group requesting a temporary residence permit for victims of trafficking in human beings. This permit offers a reflection period to consider cooperating with the investigation and prosecution of their alleged traffickers, and gives the right to income, shelter and support. Under certain conditions continued residence after the reflection period is possible.6 In most cases there was no hard evidence of victimization. Very few cases led to criminal investigations and in only 18 of the 49 client files analysed by Nidos guardians, concerning 17 girls and only one boy, these guardians were convinced that the UMAs concerned had come to the Netherlands in the context of international trafficking in human beings. In 11 cases (most of them boys) they believed this was not the case, in 20 cases (boys as well as girls) they were unsure. This shows how difficult it is to identify victims of trafficking in human beings. Security measures One of the objectives of the Dutch government was to decrease the number of disappearances amongst UMAS at risk. In this context, various security measures were realized, which differed both by location (north and south Netherlands) and by phase (first and second). © 2014 The Authors. International Migration © 2014 IOM The Protection of Unaccompanied Minor Asylum Seekers at Risk 55 The security measures implemented in first phase locations in the north and in the south of the Netherlands were largely comparable. There was a 24-hour presence of personnel and camera surveillance, the doors were locked, mobile phones had to be handed in when entering, the use of the internet was not allowed and UMAs were accompanied outdoors. Furthermore, the Immigration Service visited the UMAs in the Protected Reception locations, rather than requiring them to travel to an immigration office. In the north of the country UMAs received education and saw their lawyers outside the location, while this happened indoors in the south. In addition, only in the south were key-cards used. In second phase locations, the level of security was lower than in first phase locations. While most security measures were still in place in both the north and south of the Netherlands, the UMAs could enter and leave the building on their own. In the northern second phase locations, doors were not locked and camera surveillance was not used. The main difference between the locations in the north and south was that, in the south, the UMAs in the first and second phase lived in the same building. If necessary, the level of freedom could be increased or decreased. In the north, UMAs were generally not returned to a first phase location once having moved to a second phase location. However, the larger degree of freedom in a second phase location could be reversed. Coaching In addition to constant supervision, UMAs also received coaching from their guardians and the social workers working in the Protected Reception centres. In addition to “group coaching”, each UMA had weekly talks with a social worker assigned as their mentor, if necessary with the help of an interpreter. Also, every few weeks they met their guardian, sometimes together with their mentor. All this was aimed at, among other things, increasing their awareness of human trafficking, as well as their skills for living independently and their assertiveness. UMAs moreover received legal assistance concerning asylum and the Residency Regulation Human Trafficking. Also, an alternative perspective was provided: filing a complaint or returning to the country of origin instead of contacting the travel agent or trafficker. Interestingly, different working methods regarding supervision were applied in Protected Reception in the north and south of the Netherlands. This was partly as a result of prior experiences: while the supervisors in the northern centres had been involved in various criminal investigations, this was never the case for the southern location. Protected Reception in the north held an “investigative perspective” mainly focused on preventing disappearances. In this context, the supervisors at the reception centre employed a “healthy suspicious attitude”, meaning that they were constantly alert. This mind-set had developed as a result of past experiences when many minors disappeared from the reception centres. Staff members assumed that the majority of their residents were indeed (potential) victims of human trafficking. In the south, the working method was based on a “helpfulness perspective”: the reception centre functioned as a warm home where a family feeling was created and the UMAs (girls only) received affection and attention. Exploited UMAs and potential victims Providing support to potential victims of trafficking proved significantly more difficult than in the case of UMAs who had already been exploited. While the first group would often (strongly) protest against the implemented protection measures, as they could not believe they were brought to the Netherlands to be exploited, the second group was generally grateful for the protection offered. Potential victims of human trafficking thus needed to be persuaded that they had been brought to the Netherlands under suspicious circumstances and that they might be in danger. For this reason © 2014 The Authors. International Migration © 2014 IOM 56 Galloway, Smit and Kromhout communication between the two groups was encouraged, as UMAs who had already experienced an exploitative situation could inform potential victims of human trafficking of the dangers that might be awaiting them. Disappearances Between 2006 and 2008, a positive development was observed with respect to disappearances of UMAs. This might indicate that Protected Reception had a positive effect on the number of disappearances. However, Protected Reception could not prevent disappearances completely; notwithstanding various security measures, some UMAs still went missing. By mid-February 2010 (the reference date used in the research), 19 children (11%) had gone missing from the UMAs who stayed in Protected Reception in 2008 and 2009. These were Indian UMAs (10), and UMAs from China (6), Ethiopia (1), Lithuania (1), and Sierra Leone (1). Once Nidos considered UMAs to be ready for follow-up reception, or when they turned 18, they were placed in regular reception centres with lower staff occupancy and less supervision hours. Out of 102 minors who were placed in follow-up (regular) reception, another 11 disappeared before the reference date. According to their guardians, not all UMAs can sufficiently defend themselves against possible exploitation or abuse when they are transferred to follow-up reception where they are coached less intensively than in Protected Reception. For them this transfer constitutes a serious risk. Influx of UMAs at risk By implementing Protected Reception, the Dutch government also aimed to decrease the influx of UMAs at risk. While the number of first asylum applications from the total group of UMAs between the ages of 13 and 17 increased during the research period (August 2006 - December 2009; see Figure 1), the number of asylum applications by UMAs who specifically belong to the risk categories decreased or remained unchanged. Figures 2 and 3 show this for Indian boys and Nigerian girls respectively. Return to the country of origin The third goal of Protected Reception was to encourage UMAs to return to the country of origin instead of re-establishing contact with the traffickers and/or disappearing. UMAs who decide to return voluntarily can receive assistance from IOM. Vulnerable migrants, such as minor victims of human trafficking, receive extra care in comparison with other returnees; an employee of a local IOM location visits the family of the minor in the country of origin before he or she leaves the Netherlands. Additionally, contact can be sought with the local police and extra financial aid is available for re-integration activities such as psychosocial care and education. However, research has shown that asylum seekers generally do not wish to return to the country of origin (Leerkes et al., 2010), and repatriation is not a subject that is easily discussed with UMAs (Kromhout and Leijstra, 2006). From the 170 UMAs who entered Protected Reception in 2008 and 2009, only three (2%) left the Netherlands. In the years 2005 to 2009, 27 UMAs returned to their country of origin from the general (unprotected) reception centres. Protected Reception does not seem to have had any impact on the number of minors who return, as their number did not increase after its implementation. However, we do not have information about return without support or intervention from IOM or the Repatriation and Departure Service, nor on return in later years. © 2014 The Authors. International Migration © 2014 IOM The Protection of Unaccompanied Minor Asylum Seekers at Risk 57 FIGURE 1 FIRST ASYLUM APPLICATIONS UMAS AGED 13-17 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 FIGURE 2 FIRST ASYLUM APPLICATIONS INDIAN BOYS AGED 13-17 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 The legal framework of Protected Reception While staying in Protected Reception locations, UMAs experienced various freedom-restricting measures. Several measures were implemented in first phase Protected Reception locations; for example, the UMAs were prohibited from freely contacting people outside the centres. During © 2014 The Authors. International Migration © 2014 IOM 58 Galloway, Smit and Kromhout FIGURE 3 FIRST ASYLUM APPLICATIONS NIGERIAN GIRLS AGED 13-17 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 phase two, security measures decreased and the UMAs were granted more freedom of movement. One should keep in mind, however, that in the latter phase additional freedom restrictions could be implemented again if necessary. Looking at Protected Reception from the perspective of relevant (international) legislation and regulations, case law and literature showed that the placement and stay in Protected Reception had to be qualified as a deprivation of liberty. UMAs were expected to stay at the location, they could only go outside under supervision, and they were traced and returned to Protected Reception when they ran away. Furthermore, constant supervision and control was in place. The measurements in Protected Reception exceeded “restriction of liberty”, as the supervision and instructions in Protected Reception went further and were based on the premise that the minors could not leave the location. Moreover, this situation continued for a considerable period (at least for a few months), whereby it was difficult to say when the deprivation of liberty ended, since it was not entirely clear when phase one proceeded to phase two. According to the legal research (Liefaard, 2010), Dutch legislation did not offer legal grounds for this deprivation, making it a violation of both international human rights treaties and the Dutch Constitution. Also, the necessary judicial review was lacking, and the UMAs did not receive any legal aid regarding their placement in Protected Reception. This called for changes to either Dutch legislation and regulations, or to the practical implementation of Protected Reception. The authorities opted for the latter course. PROTECTED RECEPTION AFTER THE PILOT After the pilot, Protected Reception for UMAs solely continued in the north of the Netherlands, with capacity for 66 UMAs7 identified as potential victims of trafficking in human beings. Protected Reception still uses a phased approach, but UMAs in different phases are no longer placed in separate residential units. Nowadays, UMAs in Protected Reception can always go outside, if necessary accompanied, and those who really want to leave are moved to another reception centre © 2014 The Authors. International Migration © 2014 IOM The Protection of Unaccompanied Minor Asylum Seekers at Risk 59 without specific protection measures. Although there is still camera surveillance and doors can be locked, this only happens occasionally in emergency situations. At such times private security can be hired. Another difference is that there are more boys and more nationalities among the UMAs in Protected Reception than during the pilot. Unlike their predecessors in the pilot, UMAs usually are not eager to leave. As a result, the atmosphere in Protected Reception is more relaxed now, with fewer tensions and less opposition among the UMAs.8 These changes in practice suggest that Protected Reception no longer entails a deprivation of liberty of the UMAs concerned, although only a closer look and thorough legal evaluation can determine this with certainty. It is a fact that, despite the reduction of security measures, disappearances from Protected Reception only occur sporadically. According to the State Secretary of the Dutch Ministry of Security and Justice, this happened only once in 2012. It concerned an UMA who was later located abroad and reunited with the mother (House of Representatives, 2012-2013, 27 062, no. 89). In some respects the situation has not changed since the pilot phase: UMAs who have stayed in Protected Reception may still be vulnerable when they turn 18 and have to leave. It was therefore decided that UMAs at risk may stay in Protected Reception for at least three months, even if they turn 18 in the meantime. Furthermore, one of the general reception centres runs a programme with extra attention and support for girls who left Protected Reception but still need support with respect to safety and defensibility (Nidos, 2013). DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION The reception of UMAs at risk is a complicated matter. UMAs, and especially UMAs at risk of disappearing, are extremely vulnerable and need protection. An important question is how far the state can go in protecting these vulnerable youngsters, by – to some extent – limiting their freedom of movement, while there is evidence of psychological harm associated with alien detention (Robjant, Hassan and Katona, 2009), and other restrictive immigration policies (Dudley, Steel, Mares and Newman, 2012). Our study of the two-year pilot “Protected Reception” for UMAs in the Netherlands shows that the three objectives that were set by the Dutch government when implementing the pilot were met to some extent: the influx of risk groups and the number of disappearances decreased. However, there was no increase in return migration to the country of origin, at least not immediately after leaving Protected Reception. Another important conclusion is that the placement and stay in Protected Reception had to be qualified as a deprivation of liberty for which Dutch legislation did not offer any grounds. This called for either adjustments to the legislation, or changes in practice by limiting the deprivation. The latter occurred: security measures were lowered and the atmosphere in Protected Reception became more relaxed. These changes in practice suggest that Protected Reception no longer entails a deprivation of liberty of the UMAs concerned, although only a closer look and thorough legal evaluation can determine this with certainty. Despite these changes, disappearances from Protected Reception only occur sporadically. It seems possible to prevent vulnerable UMAs from disappearing by placing them in Protected Reception, even with lower security measures than were implemented initially. However, we do not know which of the presumed mechanisms in the policy theory (see second paragraph) were actually effective, or why initially some of the UMAs still went missing. Furthermore, in most cases there is no solid evidence that the UMAs who were placed in Protected Reception had indeed been exploited or were destined to be exploited. According to Nidos, in 2012 many UMAs in Protected Reception reported their case to the police, but almost all resulted in a dismissal, meaning that these UMAs were either not victims of trafficking after all, or not officially recognized – or recognizable – as such. © 2014 The Authors. International Migration © 2014 IOM 60 Galloway, Smit and Kromhout It must also be noted that, even if Protected Reception had a deterrent effect on the traffickers, this does not imply that less UMAs are trafficked on a global scale. Such a decrease might be the result of a “waterbed effect”, meaning that the decrease goes hand in hand with an increased influx of UMAs at risk in other EU countries. EMN figures (European Migration Network (EMN), 2010) indicate that this may have been the case for Nigerian UMAs. For example, while the Netherlands witnessed fewer applications for asylum and for a temporary residence permit for victims of trafficking in human beings from this group in 2008, Austria and Ireland received a substantial (and increased) number. However, this effect seems to have been of a temporary nature. Figures from Eurostat9 indicate that the number of applications from Nigerian UMAs in these two countries decreased during the following years.10 One should however bear in mind that asylum figures may only partially reveal a possible “waterbed effect”, as minors do not always apply for asylum. For example, many UMAs who enter Spain and Italy do not request asylum (European Migration Network (EMN), 2010) but instead remain in the country illegally NOTES 1. The aliens police checks the identity and residence status of foreigners and registers the outcome in its immigration system. 2. www.nidos.nl 3. The WODC conducts research at the request of the Dutch Ministry of Security and Justice. Its scientific independence is guaranteed by the fact that studies are supervised by an independent advisory committee, almost always chaired by an independent scholar. Furthermore, every WODC study is published. These guarantees are laid down in a covenant between the Ministry and WODC. 4. Fifty-eight files were eligible for analysis by the guardians, of which 49 were actually analysed. 5. In addition, ten babies – UMAs’ children – were admitted. 6. Aliens, including UMAs, who have been granted asylum receive a temporary residence permit which can be converted into an indefinite residence permit after five years (Aliens Act 2000, art. 28). UMAs who are denied asylum will be sent back to their country of origin if suitable reception (with family or in a reception centre) is available. A specific UMA residence permit, which allowed UMAs who had been denied asylum to stay in the Netherlands until their 18th birthday, was abolished on the first of June 2013 (House of Representatives, 2011-2012, 27062 no. 75 and 2012-2013, 27062 no. 88). 7. At the time of writing (2013) there is room for 60 UMAs. 8. Information from Nidos and the Central Agency for the reception of Asylum Seekers. 9. http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/submitViewTableAction.do (consulted July 7, 2012) 10. In the years 2009 to 2011, in Austria 115, 55 and 20 Nigerian UMAs applied for asylum; in Ireland this involved 20, 10 and 0 UMAs. On the other hand, in 2010 the Netherlands witnessed a temporary increase: five Nigerian UMAS in 2008, 10 in 2009, 20 in 2010 and five in 2011. REFERENCES Boermans, B. 2009 Uitgebuit en in de bak! Slachtoffers van mensenhandel in vreemdelingendetentie, BLinN-Humanitas/Oxfam Novib, Amsterdam (in Dutch). Chase, E. 2010 “Agency and silence: young people seeking asylum alone in the UK”, British Journal of Social Work, 40: 2050–2068. Delbos, L. 2010 The reception and care of unaccompanied minors in eight countries of the European Union, France Terre d’Asile, Paris. © 2014 The Authors. International Migration © 2014 IOM The Protection of Unaccompanied Minor Asylum Seekers at Risk 61 Derluyn, I., V. Lippens, T. Verachtert, W. Bruggeman, and E. Broekart 2009 “Minors travelling alone: A risk group for human trafficking?” International Migration, 48(4): 164–185. Dudley, M., Z. Steef, S. Mares, and L. Newman 2012 “Children and young people in immigration detention”, Curr Opin Pshychiatry, 25: 285–292. Dutch Secretary of State 2013 Letter about Unaccompanied Minor Asylum Seekers (in Dutch), Tweede Kamer der Staten Generaal, The Hague. European Migration Network (EMN) 2010 Policies on reception, return and integration arrangements for, and numbers of, unaccompanied minors- an EU comparative study, European Migration Network, Vienna. European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights 2011 Separated, asylum-seeking children in European Union Member States, European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, Luxembourg. Hancilova, B., and B. Knauder 2011 Unaccompanied Minor Asylum-seekers: overview of protection, assistance and promising practices, IOM, Budapest. Hedjam, S. 2009 Disappearing, departing, running away. A surfeit of children in Europe, Terre des Hommes, Lausanne. Kromhout, M.H.C., T. Liefaard, A.M. Galloway, E.M.Th. Beenakkers, B. Kamstra, and R. Aidala 2010 Tussen beheersing en begeleiding (in Dutch), WODC, The Hague. Leerkes, A., M. Galloway, and M. Kromhout 2010 Kiezen tussen twee Kwaden (in Dutch), WODC, The Hague. Liefaard, T. 2010 “De juridische grondslag van de beschermde opvang”, in: M.H.C. Kromhout, T. Liefaard, A.M. Galloway, E.M.Th. Beenakkers, B. Kamstra and R. Aidala, Tussen beheersing en begeleiding (in Dutch), WODC, Den Haag: 119–152. Nidos 2013 Jaarverslag 2012(in Dutch), Stichting Nidos, Utrecht. Pearse, J.J. 2011 “Working with trafficked children and young people: complexities in practice”, British Journal of Social Work, 41(8): 1424–1441. Robjant, K., R. Hassan, and C. Katona 2009 “Mental Health implications of detaining asylum seekers: systematic review”, British Journal of Psychiatry, 194: 306–312. Van den Borne, A., and K. Kloosterboer 2005 Inzicht in uitbuiting: Handel in minderjarigen in Nederland nader onderzocht (in Dutch), ECPAT Nederland, Defence for Children International Nederland, Unicef Nederland, Plan Nederland, Amsterdam. © 2014 The Authors. International Migration © 2014 IOM