ficking, Exploitation and Migration on the Traf Thailand-Burma Border: A Qualitative Study

advertisement

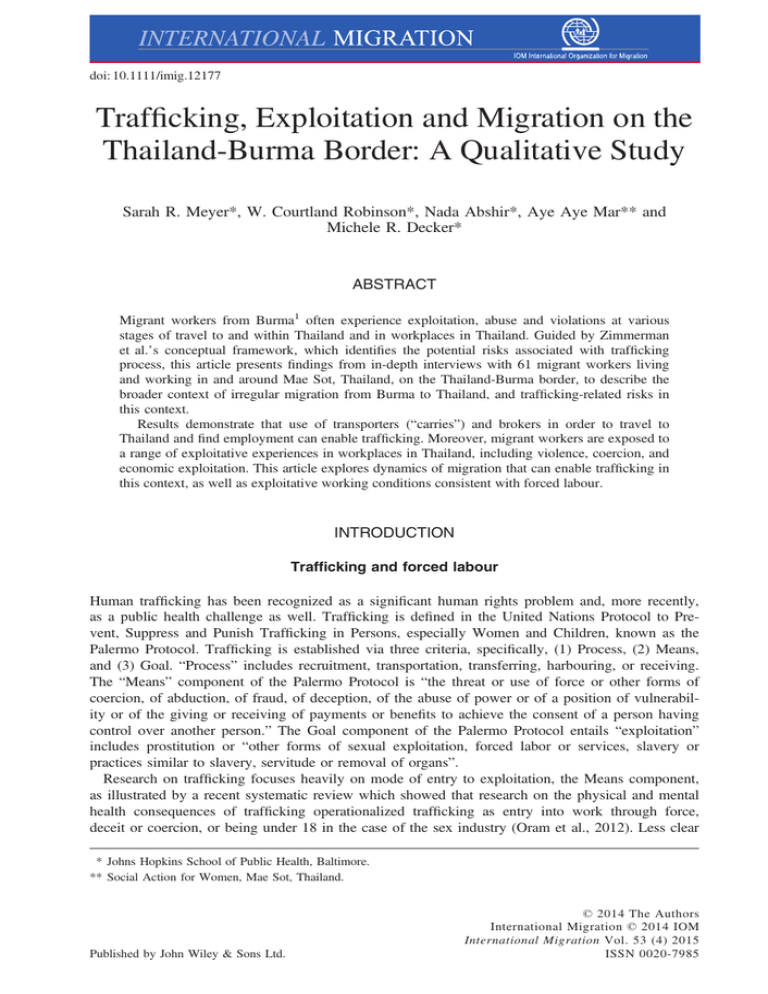

doi: 10.1111/imig.12177 Trafficking, Exploitation and Migration on the Thailand-Burma Border: A Qualitative Study Sarah R. Meyer*, W. Courtland Robinson*, Nada Abshir*, Aye Aye Mar** and Michele R. Decker* ABSTRACT Migrant workers from Burma1 often experience exploitation, abuse and violations at various stages of travel to and within Thailand and in workplaces in Thailand. Guided by Zimmerman et al.’s conceptual framework, which identifies the potential risks associated with trafficking process, this article presents findings from in-depth interviews with 61 migrant workers living and working in and around Mae Sot, Thailand, on the Thailand-Burma border, to describe the broader context of irregular migration from Burma to Thailand, and trafficking-related risks in this context. Results demonstrate that use of transporters (“carries”) and brokers in order to travel to Thailand and find employment can enable trafficking. Moreover, migrant workers are exposed to a range of exploitative experiences in workplaces in Thailand, including violence, coercion, and economic exploitation. This article explores dynamics of migration that can enable trafficking in this context, as well as exploitative working conditions consistent with forced labour. INTRODUCTION Trafficking and forced labour Human trafficking has been recognized as a significant human rights problem and, more recently, as a public health challenge as well. Trafficking is defined in the United Nations Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children, known as the Palermo Protocol. Trafficking is established via three criteria, specifically, (1) Process, (2) Means, and (3) Goal. “Process” includes recruitment, transportation, transferring, harbouring, or receiving. The “Means” component of the Palermo Protocol is “the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person.” The Goal component of the Palermo Protocol entails “exploitation” includes prostitution or “other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labor or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or removal of organs”. Research on trafficking focuses heavily on mode of entry to exploitation, the Means component, as illustrated by a recent systematic review which showed that research on the physical and mental health consequences of trafficking operationalized trafficking as entry into work through force, deceit or coercion, or being under 18 in the case of the sex industry (Oram et al., 2012). Less clear * Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, Baltimore. ** Social Action for Women, Mae Sot, Thailand. Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd. © 2014 The Authors International Migration © 2014 IOM International Migration Vol. 53 (4) 2015 ISSN 0020-7985 38 Meyer, Robinson, Abshir, Mar and Decker is the Process component, which entails the interconnections between Process, Means and Goal are often not well understood. This article presents data from a study focusing on all components of the Palermo framework, using an approach that seeks to identify elements of each of these components in the context of migration on the Thailand-Burma border. Understanding the contextual dynamics of migration and trafficking is vital for efforts to identify, protect and provide services for individuals who have been trafficked. In order to remedy injustices associated with human trafficking, a first step is identifying trafficking-related risks in a given context, in essence, contextualizing the Palermo Protocol definition in order to make it practical and applicable to this context. The Palermo Protocol informs policy and programming at a global level. It has been incorporated into domestic criminal law to varying degrees, but its framework exerts considerable normative influences over policy and programmatic approaches to trafficking globally (Shamir, 2012). Therefore, accounting for how the key elements of the Protocol operate at a contextual level is an significant step towards linking the individual experiences of migrants – who may be susceptible to or experience trafficking in this specific context – to effective policy and programmatic approaches to preventing and addressing trafficking. This article describes irregular migration from Burma to Thailand and subsequent labour experiences, and identifies components that may enable or constitute trafficking in this context. As discussed subsequently, aspects of the migration policy framework in Thailand can induce vulnerability and exposure to significant risks during migration, as well as in subsequent workplaces in Thailand, for individuals migrating from Burma. From the perspective of promotion and protection of human rights and public health, identification and understanding of these experiences is an important first step towards improving approaches towards support and assistance of individuals who experience trafficking. Trafficking policy and research often discusses the “root causes” of trafficking, noting that, for example, that “(r)oot causes for trafficking include poverty, discrimination, violence and the general insecurity often related to armed conflict” (OECD, 2008). In the context of South East Asia, Skeldon noted, “the elimination of trafficking is unlikely to be realistically improved. . .(without) improvements in the socio-economic status of the population” (Skeldon, 2004). Assessment and recognition of vulnerability as a factor that contributes towards the risk of trafficking is important, both empirically and in the terms of the Palermo Protocol (UNODC, 2012), and may constitute an approach towards prevention of trafficking (Todres, 2011). However, whereas these root causes may generally contribute towards conditions that enable trafficking, identification of these factors as causes of trafficking does not adequately account for the experiences and events which actually lead to and constitute trafficking. As Kneebone and Debeljak have argued, poverty and gender – commonly discussed root causes – may contribute towards vulnerability, but focus on these factors can shift the focus from policies and structures that facilitate trafficking, including migration policies and access to labor rights in destination countries (Kneebone and Debeljak. 2012). Zimmerman et al have developed a framework that identifies “the migratory and exploitative nature of a multi-staged trafficking process” (Zimmerman et al., 2011). Zimmerman et al.’s framework (hereafter referred to as the Zimmerman framework) outlines phases of trafficking including recruitment, travel and transit, exploitation, and for some, integration and reintegration, and detention and re-trafficking. Moreover, the framework identifies the types of risks individuals may encounter at these various stages, including psychological, physical and sexual abuse, economic exploitation and debt-bondage, legal insecurity and occupational hazards associated with abusive and exploitative working conditions. Integrating the Palermo Protocol definition and the Zimmerman framework enables an examination of three components of trafficking, and the risks that characterize each component, or phase, of trafficking. This approach to risks analysis is systematic and theoretically grounded, combining the legal framework of the Palermo Protocol with a public health analysis of risks (Todres, 2011). In the Palermo Protocol, “Process” maps primarily onto the “recruitment” phase of the Zimmerman © 2014 The Authors. International Migration © 2014 IOM Trafficking, exploitation and migration on the Thailand-Burma border 39 framework, when “individuals are vulnerable to deceptive offers to migrate for work or are abducted for the purposes of exploitation.” The “Means” component of the Palermo Protocol maps to the travel-transit stage, which “begins after an individual agrees to or is forced to depart”, and ends at the exploitation phase. In the Zimmerman framework, the “exploitation stage” is described as including “forced labor and debt bondage, sexual abuse, physical violence, psychological coercion or abuse, deprivation and confinement and usurious financial arrangements.” This framework was selected to guide the current study, given existing knowledge on the risks and potential for exploitation in workplaces in Thailand, as discussed below. Moreover, this approach addresses the lack of empirical data on the mechanisms through which migration and trafficking are interconnected in this context. A 2008 review of data on trafficking found that the majority of published literature on trafficking is not based on empirical research, and that significant gaps on actual mechanisms of trafficking exist (Gozdziak and Bump, 2008). Efforts to identify and support migrant workers who have experienced trafficking can be informed through an improved understanding of the potential risks of trafficking and the mechanisms through which migrants may experience trafficking. Migration and trafficking from Burma to Thailand: There are approximately 2.4 million migrants from surrounding countries residing in Thailand, the majority of whom come from Burma (Huguet et al., 2011). Primary occupational sectors employing migrant labour include domestic work, agriculture, fishing and seafood processing, factory work and service industries, each characterized by differing working and living conditions (ILO, 2006). Thailand is a “source, transit and destination country” for trafficking, and therefore focus on the migration processes from Burma to Thailand is needed in order to identify the key risks migrants face and points of potential vulnerability to trafficking (Piper, 2005). Migrant workers from Burma who come to Thailand may be trafficked into various occupations, including the sex industry, with trafficking in persons closely connected with broader migration, including refugee movement, patterns (Caouette, 2006; Gjerdingen, 2009). Migrant workers from Burma in Thailand are often “irregular migrants” – migrants who enter through channels that are outside the legal modes of entry in Thailand, and thus often lack legal status, leaving them vulnerable to abuse, exploitation, and threat of deportation.2 The lack of clarity on the numbers of migrants from Burma in Thailand emphasizes the ways in which migrants can be invisible within Thai society, increasing and reinforcing risks for abuse and exploitation. A variety of exploitation experiences for migrant workers from Burma in Thailand have been identified including limitations of migrants’ mobility through direct employer control (Kusakabe and Pearson, 2010), unsafe and unsanitary working conditions (Caouette et al., 2006), lack of legal protections, including minimum wage and guaranteed time off work, and denial of the right to unionize (Mon, 2010, Huguet et al., 2012), and verbal, physical and sexual abuse by employers and authorities (Amnesty International, 2005; Human Rights Watch, 2010; Kusakabe and Pearson, 2010). However, improved understanding is needed of the processes that link travel to and entry into work in Thailand with these forms of exploitation . While the Palermo protocol provides a general framework for identifying trafficking, our study seeks to clarify which aspects of this definition may predominate in a specific situation of irregular migration, and how these components are connected and interrelated against the backdrop of migration. This article describes the dynamics of irregular migration from Burma to Thailand and subsequent labour experiences, and identifies components that may enable or constitute trafficking in this context. The perspective of a 2005 review of the literature, noting that data and analysis on trafficking in the Greater Mekong Subregion is “largely fragmented,” is still relevant (Piper, 2005). Therefore, this study is situated within the need to better understand the potential risks to migrants in this context, and how these risks may be linked to trafficking. © 2014 The Authors. International Migration © 2014 IOM 40 Meyer, Robinson, Abshir, Mar and Decker METHODS Location The study was conducted in Mae Sot, a town and district in Tak Province, Thailand, located four kilometers from the Thai-Myanmar Friendship Bridge that crosses the Thailand-Burma border. Mae Sot is located near “one of the most porous parts of the Thai-Burma border”, with numerous individuals crossing the Moei River from Burma into Thailand daily, for day-labour and longer term stays for work (Feinstein International Center, 2011). Mae Sot is a major point of transit for migrant workers from Burma seeking to travel to other parts of Thailand, including Bangkok, as well as a final destination for migrant workers. Agricultural work is a major sector of employment for migrant workers from Burma, and as such, the district of Phop Phra, an agricultural area close to Mae Sot, was an additional site of interviews. Study sample The research used purposive sampling, whereby the sample was selected in order to answer the specific research questions for the study (Marshall, 1996). Formative work indicated that distinct types of occupations of migrant workers, which may be associated with specific migration, trafficking and exploitation experiences. As such, the following occupation types were included in the sample: agricultural workers, workers in small and large factories, women involved in the sex industry, and a small group of other workers (including construction workers). Overall inclusion criteria were that the respondent was 18 or over, and from Burma, currently living or working in and around Mae Sot, Thailand. The final sample, including gender, type of work, age and length of time in Thailand of respondents, is presented in Table 1. TABLE 1 DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS OF SAMPLE Type of work Large factory – Mae Sot town Small factory – Mae Sot town Agriculture – Phop Phra Sex industry Other (returned from Bangkok, construction) Age 18-24 25-34 35-44 45-54 Length of time in Thailand Under one year 1-2 years 2-5 years 5-10 years 10-15 years 15-20 years Male Female 6 4 10 N/A 7 6 10 8 10 0 5 12 8 2 9 15 8 2 2 4 8 7 4 2 1 2 18 8 4 1 © 2014 The Authors. International Migration © 2014 IOM Trafficking, exploitation and migration on the Thailand-Burma border 41 Study procedures Researchers developed an in-depth interview guide using themes that emerged in the formative research phase. The guide focused on the domains of travel and transit to Thailand, experiences living and working in Thailand, and health status and well-being – including physical and mental health, and access to health services. Interviews were conducted in Burmese by a research team trained in qualitative research methods, including human subjects research ethics. Interviews were transcribed, and subsequently translated into English for analysis. Procedures were conducted in accordance with international standards on research with trafficked persons (Zimmerman, 2003), and were approved by both the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board (IRB) and a local IRB comprised of Mae Sot community leaders. This research is part of the Trafficking Assessment Project (TAP), implemented by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in collaboration with Social Action for Women (SAW), a Burmese community-based organization, located in Mae Sot, Thailand. Analysis Analysis was based on a codebook developed as a way of categorizing data into meaningful areas of inquiry (Creswell, 2007). An initial codebook was developed by hand-coding ten interviews representing a range of experiences captured in the sample. The codebook was supplemented and some codes merged or clarified based on initial coding of interviews in Atlas.ti, using the constant comparative method to synthesize data (Boychuk Duchscher and Morgan, 2004). A single researcher utilized the codebook to code all interviews using Atlas.ti. RESULTS Use of carries and brokers Many respondents described using transporters, known as “carries”3 or brokers, at some point of their travel to or within Thailand, often as they were unsure of how to travel to Thailand or did not have existing contacts, such as friends or family members already working in Thailand, to help facilitate travel. Respondents described carries as individuals from Burma, many of whom had lived and worked in Thailand for a long time, who earned money transporting individuals from Burma to Thailand, and sometimes also played a role helping the migrant find a job in Thailand: The carry was from our village. . .He had good relationships with the police and village-heads as he would pay money to them. He was one of the influential people in our village. Male, age 29, working in large factory Some carries were described as traders who knew the routes to Thailand and therefore were able to facilitate travel: This woman lived in our quarter. . .She was like a broker or trader. She went to Thailand; bought the commodities and sold back in Burma. There were so many people she knew in Thailand. So when somebody wanted to work in Thailand, they just had to give 10,000 Kyat (US$11)4 to her and she would look for a good job for them. Female, age 25, working in a small factory Carries operate within the migration route from Burma to Thailand, as well as routes within Thailand, for migrant workers who seek to move to Bangkok or fishing areas near Bangkok. © 2014 The Authors. International Migration © 2014 IOM 42 Meyer, Robinson, Abshir, Mar and Decker Other individuals involved in the migration process are brokers – individuals who specifically facilitate migrants obtaining work in Thailand. For example, a respondent described meeting a woman near the border after she arrived in Thailand: She told me that if you didn’t know how to go, you would be cheated by others; there were a lot of liars; you shouldn’t trust the people. And she said that if we didn’t have any jobs and wanted a job, she could arrange for us. She had been in Thailand for a long time; she knew what happened where; if we wanted a job, she would help contact. She asked what kind of job we wanted, in factories or selling things. Female, age 27, sex industry Carries and brokers are central to both the recruitment phase of travel to Thailand from Burma, and the travel and transit phases. Carries and brokers were described as offering promises of good jobs in Thailand, often in order to convince individuals to come with them to Thailand. For example: A woman, who used to come to our village to sell the Thai products monthly, told me that there are good paying jobs available in Thailand. . .She promised me to get a job as she had many friends, who could find the jobs such as factories, domestic maid, sale assistant or working in the restaurant in Thailand. Female, age 29, working in agriculture Carries were regularly described as promising that migrants can “earn a lot every month” in Mae Sot (female, age 23, sex industry), that “the jobs in Mae Sot are good, the income can be fine, and the factories in Mae Sot need a lot of workers” (male, age 36, working in large factory). The activities of carries and brokers are well aligned with the Zimmerman framework’s description of the “travel and transit” phase as characterized by “deceptive offers to migrate for work”, suggesting the potential for trafficking to result from use of carries and brokers. Debt and travel to and within Thailand Migrant workers described incurring debt for travel to and within Thailand and that carries and brokers often tried to convince them that they should incur debt in order to access higher-paying jobs in Thailand and could pay the costs back later. For example, one respondent described meeting a man in her village in Burma who: told me that if I wanted to go to Bangkok, he can bring me there. He was also the one who brought other people to Bangkok and he had worked there for a long time. People trusted him. If they didn’t have money, they could give him later. He looked for a job for them. He took the money from employers in advance and we had to agree to pay it back. Female, age 32, sex industry For one respondent, a carry she met in Burma told her: if I wanted to go to Bangkok; he could find a job in a factory processing fish cans. When I said I have no money to go to Bangkok, he told me to give 100,000 Kyat (US$112) to him first and I could gradually give him back the remaining 200,000 Kyat (US$224) later. Female, age 26, sex industry Deceit For some migrant workers who used a carry to travel from Mae Sot to Bangkok, this directly resulted in their being forced to work without pay, often in working conditions to which they had not agreed. Deceit about the amount of debt, how debt would be paid off, and working conditions were components of both recruitment and travel and transit. Deceit was reported at different phases © 2014 The Authors. International Migration © 2014 IOM Trafficking, exploitation and migration on the Thailand-Burma border 43 of migration and entry into forced labour, however, respondents primarily described instances in which they only found out about the amount of debt owed after starting to work. As such, deceit is present in all phases of the process – recruitment, travel and transit, and exploitation. In some cases, carries and brokers deceived migrant workers about the amount of debt they had incurred in order to travel to Thailand. For example, one respondent reported, about his experience travelling with a carry from Burma, that after they arrived at their destination, he experienced limitations on freedom of movement given the debt he had to pay back: We were not allowed to go out. He told us that we could be arrested by police if we went out. Later, he took the girls to some place. I didn’t know where. I was afraid to ask. On the next day, he told us that he would go out and look for the jobs for us. . ..(he) arranged us to work on the boats. He told us how much we would make and how many months we had to work for free for the money that we owed him for the trip. He reminded us that it would be very dangerous for us if we tried to run away. Male, age 31, working in a large factory He was forced to work without pay on a fishing boat for three months in order to pay off his debt. This debt can lead to limitations in ability to change jobs; as a 23 year-old male agricultural worker explained that after he had arrived at his job in Thailand, after travelling with a carry from Burma, “the boss didn’t allow us to move to the other job for five months. He claimed that we owed him for our travel costs that he spent.” Migrants also described being deceived about working conditions and the nature of work they agreed to. A 31 year-old male working in a large factory described having been deceived as to the nature of work he agreed to. He was told by a broker that he would be doing an easy job, but after arriving near Bangkok, was forced to work for free for three months on a fishing boat, working long hours in difficult and abusive conditions. He explained, “he (the broker) reminded us that it would be very dangerous for us if we tried to run away. He said that there was no way possible for us to escape even if we tried.” Women involved in the sex industry most commonly described this form of deceit, whereby they were told prior to beginning work that they would be working in a restaurant, but then ended up in a venue selling sex. A 32 year-old female explained, having travelled with a carry to Bangkok, “(a)fter we arrived to the restaurant, the carries didn’t come and meet us. They didn’t tell us anything. They just met with the owner and went back. In the evening, we were given the new clothes and asked to make ourselves beautiful. And then we had to meet with the customers.” During recruitment and travel and transit phase, some women were vulnerable to deceptive offers of employment that resulted in being trafficked into the sex industry. The resulting work environment is often characterized by exploitative experiences such as work without pay, described further below. Salary deductions and forced overtime Respondents discussed a broad range of experiences of exploitation in workplaces, including salary deductions and forced overtime. Many of the experiences described were aligned with the “exploitation phase” of trafficking, suggestive of trafficking for labour and sexual exploitation in this context. Many participants described deductions for “police pay” – forced salary deductions by employers in order to pay bribes to police to ensure undocumented migrant workers are not arrested. Not only were these involuntary deductions but, in many cases, they did not protect migrant workers from arrest: As we didn’t have any documents, the boss also deducted 200 baht (US$7) per month for police pay. He told us to work well and not to worry about police arrest and that he would take responsi- © 2014 The Authors. International Migration © 2014 IOM 44 Meyer, Robinson, Abshir, Mar and Decker bility since we were in his farm. After about three months, the immigration came to the farm and arrested people. . . Although the boss deducted for the police, he didn’t help to take them back (out of jail). Male, age 31, working in agriculture An 18 year-old female working in a large factory explained, “In the factory, although 150 Baht (US$5) per month is cut from our salaries, if police come we just have to run. If we are arrested, we just have to solve (the problem) ourselves. They (the employers) don’t solve for us.” Migrant workers commonly described work environments where salary deductions were irregular, unexpected, and forced. After receiving 2,000 baht (US$68) out of a promised 12,000 baht (US$408) of his salary, a respondent explained: He (my employer) would give me only 2,000 (US$68). If I do not agree, he said that he does not care and that I can inform anybody. And he told me to leave. . .I didn’t dare to inform the police because this boss got along with the police and the immigration and he bribed them. Male, age 25, working on construction Deceit, as described above, can operate in the area of salary deductions, as deductions by employers are used to pay back carries or brokers: When the boss told me that I got total 8,700 Baht (salary) (US$296), I was so happy as it had been only a month. When she gave me, the boss told me that she had to give 5,000 Baht (US$170) to (the broker) who brought me here. And it was 2,200 Baht (US$75) for the clothes and cosmetic. So after all these deductions, I had only 1,500 Baht (US$50) left. Female, age 23, sex industry Non-payment of salary can also influence migrant workers’ ability to change jobs, for example: When we were working in the factory, the factory owner made it impossible for us to leave the factory for another job by not paying our salary. . . If we had to get 2,000 (baht), they only gave 700 (US$24) and they said they would give us next month. They always threatened us that we had been sold. Female, age 22, working in small factory Forced, and often unpaid, overtime was a commonly discussed form of exploitation. For example, one respondent stated: “The factory stole our overtime pay too. We always got paid less. For instance, if we were supposed to get 9 baht (US30 cents) for every 100 pieces of clothes, the money we got was less than we were supposed to get. We dared not speak out.” Female, age 41, working in a small factory A 23 year-old woman working in a large factory stated: “Whenever there is overtime work, we have to work. We also have to work all the night. We cannot refuse to work. If we don’t work, 50 Baht (US$1.70) per day is cut from our salaries. We are allowed only a few hours for sleeping. If overtime work start from 6pm and end at 5am in the next day, we have to start again at noon.” An 18 year-old female working in a large factory explained that she was told by a manager, “if you don’t want to work overtime, just pack your things and go.” Forced work without pay Respondents also described forced work without pay, a form of exploitation that is consistent with conditions of forced labour. As described above, one mechanism by which migrant workers found themselves in a work environment where they were not paid was through deceit about the amount © 2014 The Authors. International Migration © 2014 IOM Trafficking, exploitation and migration on the Thailand-Burma border 45 of debt, and how the debt would be paid off. A 37-year old respondent described meeting a Thai woman in Myawaddy:5 She said we had to pay when we got a job. After we arrived in Bangkok, she handed us over to another Thai woman, who is about 45 years old and left. She said that women will get a job for us, so we followed her. After getting a job as a babysitter with a Thai couple in Bangkok, she found: The promised salary was 2,000 baht (US$68) a month. At the end of the month, they told me that they had already paid for my one year’s salary to the Thai woman. Therefore, I would get paid after one year. Another respondent who had used a carry for travel explained: The boss didn’t give me salary. I had to put all the tip money into a box on the counter. The boss gave all these money to the other employees by quota except me and my fellow worker. When we asked why we didn’t get paid, he said he bought us at 20,000 baht (US$680). We would get our salaries and the money in the box after two years. I couldn’t do anything but cry at that point. Female, age 27, sex industry. One respondent paid 3,000 baht (US$100) to a carry who arranged travel to Bangkok, and after travelling by foot for 20 days with the carry and seven other migrant workers, he was taken to a place near Bangkok: When we arrived, they left us at an ice factory. They didn’t care when we refused to work there. They forcefully left us there regardless. When I asked to a worker there, he told me that I could make about 5,000 baht (US$170) a month. They all made about 5,000 / 6,000 baht a month there. After a month, I went to the boss and ask for my salary. He told me that he paid our two months salaries at 10,000 baht (US$340) to the carry. He said I would get paid after three months. Male, age 23, working in a small factory These means of deceit and abuse of power are linked to forms of exploitation experienced in work environments, as migrant workers are forced to work off their debt in unsafe and coercive working conditions. Physical and verbal abuse Participants also described violence, including physical and verbal abuse both personally experienced and witnessed, in the workplace. Employers and managers were routinely described as yelling, threatening, and sometimes perpetrating physical abuse: The boss came to work and monitored us from time to time. He would say who worked slowly and who worked fast and to work faster in broken Burmese. If we made a mistake, he would yell as us in a strange language. Female, age 30, working in agriculture Another respondent explained: If I did something wrong at work, the manager would yell at me with vulgar language. He would yell or threaten me if I took a day off during the working days. Male, age 36, working in construction © 2014 The Authors. International Migration © 2014 IOM 46 Meyer, Robinson, Abshir, Mar and Decker Extreme violence and coercion was described as characteristic of some work environments. One respondent described the restrictive and violent work environment he had previously experienced on a fishing boat: The manager was always monitoring us. If we worked slowly, we would be kicked and punched. He would do the same to the people who were physically unable to work fast. That’s the reason why people committed suicide, by jumping into the water and drowning themselves. Male, age 31, working in a large factory In some instances, migrant workers described extreme fear of employers and managers. A 35 year-old male, working on a fishing boat after being cheated by a carry, described the work environment: The manager was always cursing us. They all had guns. We had to work 24 hours a day. We were not allowed to stop until the work was done. Two Thai men threatened us with their guns. If we talked to each other while working, they would shoot in the air like a warning shot. We were afraid of them. We couldn’t talk back to them. If we said anything against them, we were beaten. Male, age 35, working in construction Respondents in the sex industry routinely described physical force as a form of compulsion, with a 32 year-old woman explaining about beginning to work: “Some girls refused to do it and were beaten. Later, they couldn’t refuse anymore and they had to do it. Later, we had to do this job.” Violence was witnessed and experienced in the course of everyday life in work environments; for example, a 46 year-old female working in agriculture reported seeing other workers “thrown to the ground strongly and kicked” by the manager. Witnessing and experiencing abuse, as well as the threat of abuse, was described as a reason that many migrant workers stayed in work environments that were unsafe, coercive and constituted forced labour. DISCUSSION Limitations Findings should be interpreted in the light of several limitations. Access to respondents depended on respondents having some freedom of movement at the time of interview. Although our sample included a number of individuals who had escaped from extremely exploitative situations, those currently experiencing extreme exploitation, fearing reprisals for participation in research, or lacking freedom of movement, remain a largely inaccessible population, which is a common problem in trafficking research (Brunovskis and Surtees, 2010). Moreover, the extent to which current findings generalize to broader populations of migrants from Burma elsewhere in Thailand, and broader contexts of irregular migration, is unclear. Findings We describe a range of exploitative experiences among migrant workers from Burma in Thailand, and identify consistency with the trafficking processes articulated by the Zimmerman framework (Zimmerman et al., 2011). Findings illustrate that migrant workers are frequently told of higherpaying jobs available in Thailand, and use carries or brokers to travel to Thailand in order to obtain this work. Incurring debt during this phase appears to be linked sequentially and systemically to experiences of various forms of exploitation in subsequent work environments. The overlap © 2014 The Authors. International Migration © 2014 IOM Trafficking, exploitation and migration on the Thailand-Burma border 47 between experiences of deceit and experiences of exploitation indicate that deceit is a mechanism through which migrant workers may be easily trafficked into forced labour or the sex industry. For some migrant workers, deception led to labour or sex exploitation, including work without pay, forced overtime, and abuse. Respondents’ descriptions of work environments in Thailand demonstrate that there is evidence of extensive exploitation amongst migrant workers, which, while varying in severity, indicates presence of forced labour in a number of occupational sectors. As such, this demonstrates the importance of a labor approach to exploitation and trafficking in this context, which emphasizes the importance of focusing on “the structure of labor markets that are particularly susceptible to trafficking,” and transforming power relations, for example, through enforcing application of labour laws for vulnerable migrants, as a means towards addressing trafficking (Shamir, 2012) Findings from this study corroborate and extend past research focused on the exploitation phase, identifying common experiences in work environments in Thailand (Arnold, 2005; Arnold and Hewison, 2005; Huguet and Charmatrithriong, 2011). As well as confirming previous research, findings from this study add to an understanding of how these experiences are interconnected with migration dynamics from Burma to, and within, Thailand. Our qualitative research with migrant workers identifies a spectrum of potential trafficking processes and experiences within migration processes and work environments in this context, indicating the embeddedness of trafficking within a labour migration context. Findings provide an important insight on the nature and role of Process as a component of trafficking. Migrants described interactions with carries and brokers who sometimes had connections to other parts of Thailand and to specific employers. The picture that emerges from the data in this present study is one of diffuse networks of individuals whose actions can cumulatively result in a process of trafficking. Friedman has argued, that for anti-trafficking interventions in the Greater Mekong Subregion, “(e)xploitation and enslavement should be our target, recognising that the transportation in human trafficking is often a peripheral factor in Southeast Asia and sometimes not a factor at all” (Friedman, 2012). However, findings from this study indicate that while the very fact of transportation may not be central, migrant workers’ interactions with carries and brokers are often characterized by deceit that can in turn lead to situations of forced labor. Thus, analysis and understanding of these processes is important. Recruitment using a carry or broker is at once both a central component of the migration process, and a key mechanism through which migrants are can be introduced into trafficking networks and systems. These findings affirm the relevance of the Process aspect of the Palermo protocol, and moreover, affirm the importance of the present study, in engaging with the global framework of trafficking, the Palermo protocol, and identifying key elements of the Process aspect and mechanisms through which Process is linked to subsequent exploitation. Our approach to Process in this study is distinct from the root causes approach, which has largely failed to account for patterns of trafficking and specific vulnerabilities generated during the migration process (UNIAP, 2007). Our approach engages with the established international legal definition and framework, and contextualizes it with empirical data. A common interpretation of the Process component of the Palermo Protocol is that all movement that is part of trafficking is forced or coerced (Gjerdingen, 2009). However, as this study shows, migration processes may begin as voluntary but then result in deception, coercion, and ultimately, forced labour and exploitation. A key component of achieving accountability and access to justice for individuals who have been trafficked in the Thailand-Burma context is to ensure that provision of services and support for individuals who have experienced trafficking is not predicated on the assumption that individuals must have been forced to travel to Thailand, in order to “count” as a victim of trafficking. Despite our current evidence illustrating processes consistent with trafficking within irregular migration from Burma to Thailand, identification of trafficked persons within this broader group is challenging in the current policy context. In Thailand’s current approach to immigration law © 2014 The Authors. International Migration © 2014 IOM 48 Meyer, Robinson, Abshir, Mar and Decker enforcement, migrants with irregular status are often framed as law-breakers; in some cases, victims of exploitation and dangerous transport and transit in Thailand are charged with illegal entry, rather than provided support services (Gjerdingen, 2009). Indeed, the US State Department’s Trafficking in Persons Report 2012 Thailand country profile noted that “the country’s migrant labor policies continued to create vulnerabilities to trafficking and disincentives to victims to communicate with authorities, particularly if the workers are undocumented” (US Department of State, 2012). The Trafficking in Persons report cites examples of where local law enforcement officials failed to identify debt bondage or threat of deportation as forms of coercion, instead believing that physical detention or confinement are necessary elements of trafficking. Elements of exploitation identified in this study may affect migrant workers in many industries, and distinctions between migrant workers in exploitative workplaces and individuals who have been victim to trafficking are neither distinct nor clear in this context. Further research and analysis is needed to identify operational definitions of trafficking in this context that reflect the empirical data, as well as adhering to international legal definitions and human rights standards. Policy implications of this research include that measures to ensure that Thai immigration regulations can serve to protect migrant workers are vital. Globally, lack of access to safe and legal ways for low-skilled workers to migrate have resulted in individuals entering into arrangements that result in trafficking (Gallagher, 2001), a dynamic that is present in this context (Huguet et al., 2012). In relation to the present case study, analysis and reform of immigration regulations that contribute towards trafficking are needed. Moreover, Thai law includes legal protections intended to extend to all workers, whether irregular or not; improved oversight and enforcement of law standards and practices could reduce exploitative experiences and forced labour of Burmese migrant workers in Thailand. CONCLUSION In this study, the objective was to explore and define key dynamics in the process of migration from Burma to Thailand, in order to highlight the salient factors consistent with trafficking in persons. Current findings clarified the use of carries and brokers as a systemic component of migration. This is interrelated with debt, deceit, and exploitative working conditions in Thailand. This study contributes towards understanding migration and its link with trafficking in this specific context by exploring and presenting processes that link travel to and entry into work in Thailand, as well as forms and patterns of exploitation that may constitute forced labour. In efforts to achieve accountability and access to justice for trafficked persons, research to inform and ground an understanding of trafficking in a particular context is an essential first step towards improved identification, law enforcement and service provision for trafficked persons. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Funding for this research was made possible by (S-SGTIP-11_GR-0024) from the Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the Department of State. We acknowledge the hard work and dedication of SAW staff who conducted the interviews for this study – Min Min, Myo Ko, Lin Dar, Thin Thin, Yee Yee Win, Myat Su – and gratefully acknowledge Shwe Zin and Thwin Linn Aung for their roles as SAW research co-ordinators for the project. © 2014 The Authors. International Migration © 2014 IOM Trafficking, exploitation and migration on the Thailand-Burma border 49 NOTES 1. The official name of the country is the Republic of the Union of Myanmar, but it will be referred to as Burma throughout this article as this is the name used by community partners. 2. Huguet et al. present the various ways in which a migrant worker entering Thailand can become irregular: (a) they may enter the country clandestinely or without approval; (b) they may enter the country with a valid document, such as a visa or day-pass, but stay longer than permitted; (c) they may be in the country legally but working without permission; (d) they may have been working with permission but their status has changed, as when the work permit expires or the migrant changes employers. (See Huguet, Charmatrithriong and Richter, 2011.) 3. Transporters were referred to by migrant workers as carries, a loan word from English used in this migration context. 4. All currency conversions are from www.xe.com and are current at time of writing. 5. Myawaddy is the town in Burma nearest to Mae Sot. REFERENCES Amnesty, International. 2005 Thailand: the plight of Burmese migrant workers, Amnesty International, London. Arnold, D. 2005 “The situation of Burmese migrant workers in Mae Sot, Thailand”, in Asia Monitor Resource Center (Ed.), Asian Transnational Corporation Outlook 2004: Asian TNCs, workers, and the movement of capital. Asia Monitor Resource Center, Bangkok. Arnold, D., and K. Hewison 2005 “Exploitation in Global Supply Chains: Burmese migrant workers in Mae Sot, Thailand”, Journal of Contemporary Asia, 35(3): 319–340. Boychuk Duchscher, J.E., and D. Morgan 2004 “Grounded theory: reflections on the emergence vs. forcing debate”, J Adv Nurs, 48(6): 605–612. Brunovskis, A., and R. Surtees 2010 “Untold Stories: Biases and Selection Effects in Research with Victims of Trafficking for Sexual Exploitation”, International Migration, 48(4): 1–37. Caouette, T., R. Sciortino, P. Guest, and A. Feinstein 2006 Labor Migration in the Greater Mekong Sub-region, Rockefeller Foundation, Bangkok. Creswell, J.W. 2007 Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, Sage Publications, London. Feinstein International Center. 2011 Developing a Profiling Methodology for Displaced People in Urban Areas: case study: Mae Sot, Thailand, Tufts University, Medford. Friedman, M. 2012 “Human Trafficking in the Mekong Region: One Response to the Problem”, Focus, 67. Gallagher, A. 2001 “Human Rights and the New UN Protocols on Trafficking and Migrant Smuggling: A Preliminary Analysis”, Human Rights Quarterly, 23(4): 975–1004. Gjerdingen, E. 2009 “Suffocation inside a cold storage truck and other problems with trafficking as ‘exploitation’ and smuggling as ‘choice’ along the Thai-Burmese border”, Arizona Journal of International & Comparative Law, 26(3): 700–737. Gozdziak, E. and M. Bump 2008 © 2014 The Authors. International Migration © 2014 IOM 50 Meyer, Robinson, Abshir, Mar and Decker Data and research on human trafficking: Bibliography of research-based literature, Institute for International Migration, Washington DC. Huguet, J.W., and A. Charmatrithriong 2011 Thailand Migration Report 2011: Migration for development in Thailand: Overview and tools for policymakers, IOM, Bangkok. Huguet, J.W., A. Charmatrithriong, and C. Natali 2012 Thailand at a crossroads: challenges and opportunities in leveraging migration for development, Washington DC, Migration Policy Institute and IOM. Huguet, J.W., A. Charmatrithriong, and K. Richter 2011 “Thailand Migration Profile”, in J. W. Huguet and A. Charmatrithriong (Eds), Thailand Migration Report 2011: Migration for development in Thailand: Overview and tools for policy makers, IOM, Bangkok. Human Rights Watch. 2010 From the tiger to the crocodle: abuse of migrant workers in Thailand, Human Rights Watch, Bangkok. ILO. 2006 The Mekong Challenge: Underpaid, Overworked and Overlooked, ILO, Bangkok. Kneebone, S. and J. Debeljak 2012 Transnational Crime and Human Rights: Responses to Human Trafficking in the Greater Mekong Subregion, Routledge, Abingdon UK. Kusakabe, K., and R. Pearson 2010 “Transborder Migration, Social Reproduction and Economic Development: A Case Study of Burmese Women Workers in Thailand”, International Migration, 48(6): 13–42. Marshall, M. 1996 “Sampling for qualitative research”, Family Practice, 13: 522–525. Mon, M. 2010 “Burmese labour migration into Thailand: governance of migration and labour rights”, Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 15(1): 33–44. OECD 2008 Trafficking in Persons as a Human Rights Issue, OECD, Paris. Oram, S., H. Stockl, J. Busza, L.M. Howard, and C. Zimmerman 2012 “Prevalence and risk of violence and the physical, mental, and sexual health problems associated with human trafficking: systematic review”, PLoS Med, 9: 5. Piper, N. 2005 “A Problem by a Different Name? A Review of Research on Trafficking in South-East Asia and Oceania”, International Migration, 43(1, 2: 203–233. Shamir, H. 2012 “A Labor Paradigm for Human Trafficking”, UCLA Law Review, 76: 76–136. Skeldon, R. 2004 “Trafficking: A Perspective from Asia”, International Migration, , Special Issue(1): 7–30. Todres, J. 2011 “Moving Upstream: The Merits of a Public Health Law Approach to Human Trafficking”, North Carolina Law Review, 89: 447–506. UNIAP 2007 Targeting Endemic Vulnerability Factors to Human Trafficking, UNIAP, Bangkok. UNODC 2012 Abuse of a position of vulnerability and other “means” within the definition of trafficking in persons, UNODC, Vienna. US Department of State. 2012 Trafficking in Persons Report, US Department of State,Washington DC. Zimmerman, C. and C Watts. 2003 WHO Ethical and Safety Recommendations for Interviewing Trafficked Women, WHO, Geneva Zimmerman, C., M. Hossain, and C. Watts 2011 “Human trafficking and health: a conceptual model to inform policy, intervention and research”, Soc Sci Med, 73(2): 327–335. © 2014 The Authors. International Migration © 2014 IOM