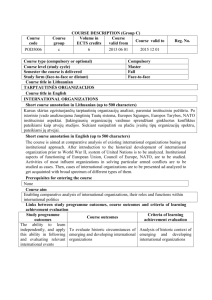

U.S. Air and Ground Conventional Forces for NATO: Mobility and Logistics Issues

advertisement