HANDBOOK DEC 09 No. 10-11 Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures

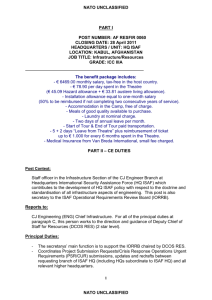

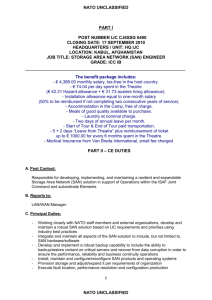

advertisement