Document 10744575

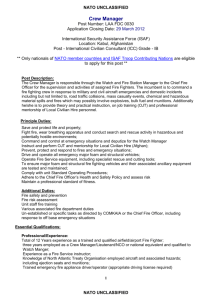

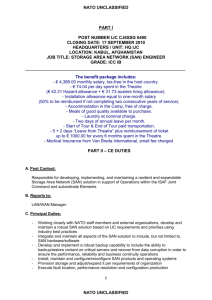

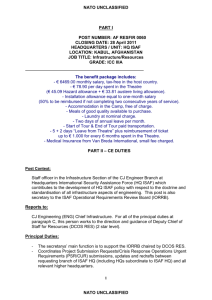

advertisement